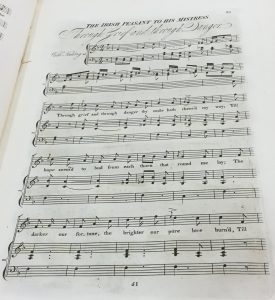

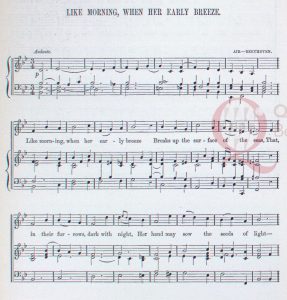

The first stage work inspired by Lalla Rookh opened at the Theatre Royal, Dublin on 10 June 1818. This was M.J. Sullivan’s adaptation of Moore’s text as Lalla Rookh; or the Cashmerian Minstrel, as set by the popular singer-composer Charles Edward Horn. He was the son of a musician, also named Charles Horn, who had moved to London from Nordhausen in 1780. Horn senior counted amongst his pupils members of the Royal Family as well as the young tenor John Braham. Charles junior, born in 1788, became a versatile musician eventually famed for his tenor voice: his first position, however, was as a double-bass player at Covent Garden theatre; he was then appointed as second violoncello at the Italian opera under Lindley; at the age of 17, he published his first ballad, “The Baron of Mowbray”. The New York Mirror (vol. 12, 1834, pp. 294-95) credits Horn with setting at least a dozen theatrical works performed in London, including Moore’s comic opera, The MP; or, The Bluestocking in 1811. (Horn’s taste in poetry, we are told, was “most refined”.) In the role of the poet Feramors for his opera Lalla Rookh, Horn would have treated his audience to his “veiled” or “husky” voice, which, combine with his “good manners and gentleman-like address” (New York Mirror), would have conveyed a certain appeal to the part.

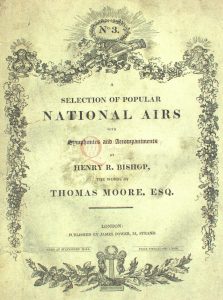

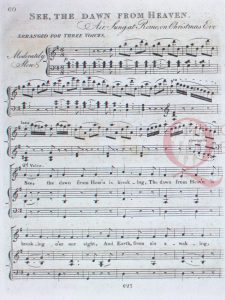

We get a mixed impression regarding the success of Horn’s Lalla Rookh. Freeman’s Journal of 11 June 1818 proclaimed two or three of the airs “beautiful”, and described the “plaudits … on every side” when Moore was observed in situ on opening night, with a further “three distinct rounds of applause” two nights later, when Moore sat in the manager’s box. The publication of the score is a further marker of expectations for the work; the title-page records its dedication to that most illustrious of society patronesses, Lady Morgan:

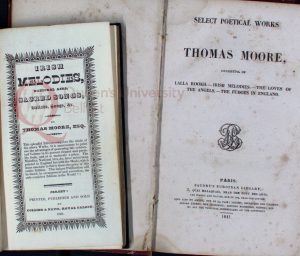

“The Overture, Songs, & Duets, / In the Operetta of / LALLA ROOKH, / Performed with unbounded applause / AT THE / Theatre Royal, Dublin. / FOUNDED ON T. MOORE, ESQ.’S celebrated Poem; / The Words by M. J. Sullivan, Esqr. / The Music Composed, and Dedicated to / Lady Morgan, / By Charles Edward Horn. / Dublin, / Printed for the Author, by I. Willis, 7. Westmoreland Street”

Yet there is no firm record of Horn’s opera entering the repertory on a long term basis, and T. Walsh (Opera in Dublin 1798-1820, p. 192) insists it did not “become a favourite”.

While Horn’s opera may not have exerted an enduring appeal, during the nineteenth century every new generation of Dublin theatre-goers had the chance to engage with Moore’s Lalla Rookh as a stage work. Freeman’s Journal for 10 March 1843 contains an advertisement for a

“New Grand Equestrian Spectacle, / in Two Acts, called / LALLA ROOKH: / Or, The AMBASSADOR OF LOVE, AND GHEBER FIRE WORSHIPPERS / In which the entire Stud will appear.”

This work featured Lalla Rookh and her poet-lover Aliris, her father the Mughal emperor Aurungzebe, as well the added characters of Zerapghan, Himlah, and Meenah. We find another kind of poplar stage entertainment in the burlesque Lalla Rookh, Khoreanbad styled as “A Grand Divertissement” and staged on 4 Oct. 1858 at the Queen’s Royal Theatre.

The Gaiety Theatre would seem to have produced the most popular entertainment founded on Moore’s poem. On 22 December 1881 Freeman’s Journal announced

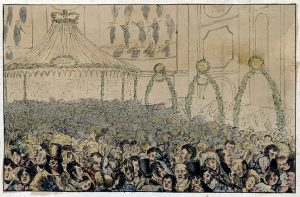

“This Evening … (at 7:30) / The Enormously Successful / The Grand Annual Christmas Pantomime, / LALLA ROOKH. / Bul Bul, the Peri: Hafed, the Gheber: and the / Feast of Roses, / Founded on Thomas Moore’s Oriental Poem. / New and Gorgeous Scenery. Magnificent Costumes. / Powerful and Specially Selected Company. / Kaleidoscopic Ballet. Exquisite Panorama. Gorgeous Marriage Revels. The celebrated Pet Elephant.”

This work was repeated at least nine times before the following notice appeared in Freeman’s Journal for 31 January 1882:

“This evening … SECOND EDITION / Of the enormously successful Pantomime / LALLA ROOKH . New Songs! New Dances! / New Medley of Moore’s Irish Melodies / New Topical Song! / New Dances and Comic Business by / The pet Elephant.”

This revision generated a further eight performances before, some fifty-five years after its source of inspiration was originally published, the Dublin public’s interest in the pantomime waned.