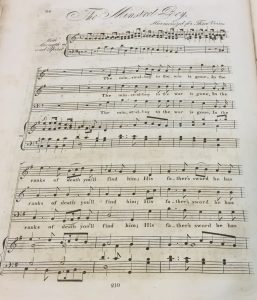

Although Moore himself was adverse to the separation of music and text for his Irish Melodies, by 1817 J.P. Reynolds – an enterprising publisher in Salem, New York— had issued Irish Melodies, Sacred Melodies, and other Poems. This appeared to open the way for a spate of similar publications across Europe, led by Moore’s Parisian agents the Galignanis, who issued various compilations of his poetic works in 1819, 1820, 1823, and 1829. This firm and Baudry’s European Library—also based in Paris—appeared to be addressing an English-language market. Moore’s four titles with Baudry (1821, 1841, 1843, and 1847) made him—along with Walter Scott and Washington Irvine—their fifth most represented author. The 1820s was the most intense decade for English-language publications of the Irish Melodies, which—in combination with the poems for the National Airs—were issued in Brussels (1822), Pisa (1823), and Jersey (1828).

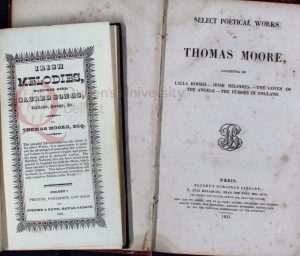

Title-pages for the Jersey (1828) and Paris (1841) editions

of Moore’s Poetry

By 1825 we also have an actual translation of Moore’s poetry, Louise Swanton Belloc’s Les amours des anges et les Mélodies irlandaises. It is interesting to note that Belloc, whose father was Irish, also translated selected works of Moore’s Irish contemporaries Oliver Goldsmith and Maria Edgeworth as well as Moore’s own Memoirs of Lord Byron for various Parisian publishers. By 1835 we have the first Swedish translation of the Irish Melodies; by 1839 the first German. Leipzig (1839, 1843, and 1874), Berlin (1841) and Hamburg (1875) each published Moore’s Irish Melodies in translation. Added to the polyglot profile of Moore’s Irish Melodies were a new French translation by Henri Jousselin (1869), a Spanish translation issued in New York (1875), and an Italian translation issued in Pisa (1880). By a strange quirk of market forces, the first Latin translation of the Irish Melodies (1835) preceded the first in Irish (1842) by some seven years. If we add to this the some seventy editions of the Irish Melodies issued by Moore’s London-based publisher Longmans, and the over 100 editions issued in Dublin, we can appreciate that Moore’s response to the native tunes of his own country held a universal appeal.

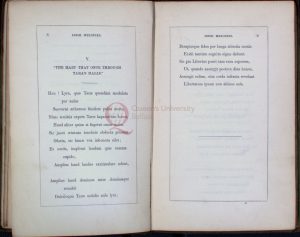

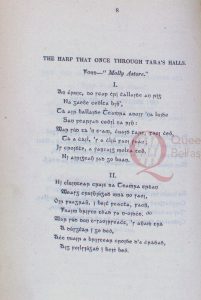

“The Harp that once in Tara’s Halls” in Latin and Irish

Are you aware of editions of the Irish Melodies at locations or in languages not mentioned here? If so, we would welcome a comment on the blog.

Images reproduced courtesy of Special Collections, McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast.