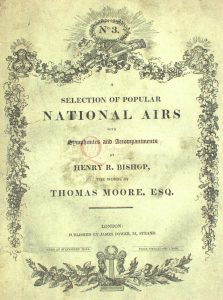

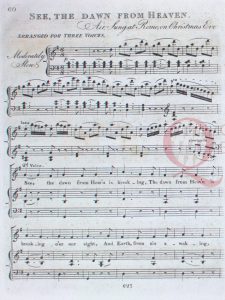

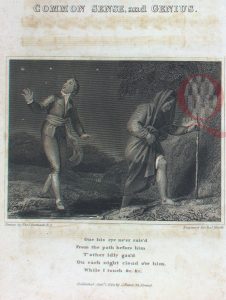

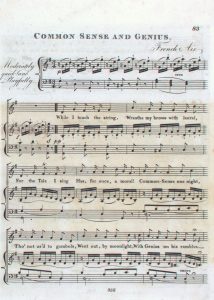

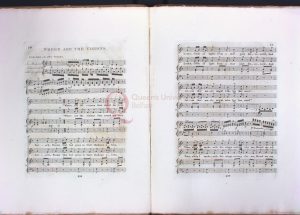

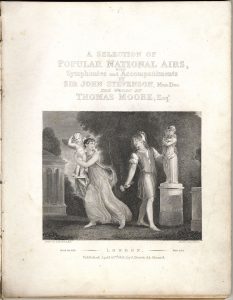

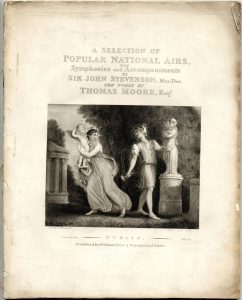

All of Thomas Moore’s works featured in project ERIN – the Irish Melodies, the National Airs, and Lalla Rookh – were conceived to feature contributions from illustrators and engravers at an early stage. With regards to the two song series, each number thereof would sport one or two plates designed by illustrators such as as Thomas Stothard RA (“Row gently here” from the National Airs; “Lesbia hath a beaming eye” from the Irish Melodies), or William Henry Brooke (“As vanquish’d Erin”, and “Oh, ye dead!,” both from the Irish Melodies). The title pages, too each had their own illustration. These designs were executed as engravings (“a printmaking technique that involves making incisions into a metal plate which retain the ink and form the printed image” –tate.org.uk) by such as Charles Heath (1785-1848) or Henry Melville (1792-1870). While the images featured in the Irish Melodies or National Airs – whether produced by James Power in London or William Power in Dublin – were ostensibly the same (i.e. drawn by the same illustrator), the fact that the brothers employed distinct engravers is evident when copies of their works are compared. One of the most famous illustrated volume associated with Thomas Moore is the 1846 edition of the Irish Melodies as illustrated by his fellow Irishman Daniel Maclise RA (1806-1870); Maclise’s work is distinct from earlier illustrated editions in presenting one or two illustrations (or at the very least a decorative border) to each of the Melodies. The popularity of this edition (which was reissued by Longmans as late as 1876) brought Moore’s work to a new generation towards the end of his life and beyond.

Lalla Rookh has a particularly strong association with illustrators. Queen Victoria’s drawing master Richard Westall RA (1765-1836) seems to have been commissioned by the Longman firm to design Illustrations of Lalla Rookh an oriental romance—since this volume came out in the same year as Moore’s ‘oriental romance’. Charles Heath (1785-1848), also associated with illustrations for the Irish Melodies, was the engraver. More famous perhaps was the edition of Lalla Rookh with sixty-nine illustrations designed by John Tenniel (1820-1914), issued several times by Longmans between 1861 and 1880. This edition already had a rival issued by George Routledge in 1860 that featured the illustrations of numerous artists, including George Housman Thomas (1824-1868), Kenny Meadows (1790-1874), and Edward Henry Corbould (1815-1905). Routledge promoted an illustrated edition of Moore’s Lalla Rookh until at least 1891. Some of these artists, as well as the engraver Charles Heath, were previously involved in an illustrated version of Lalla Rookh brought out by Longmans in 1838.

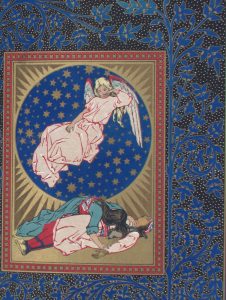

Much of the illustrative activity associated with Moore’s work took place in the Anglo-Irish orbit, and involved some fairly high profile artists. Project ERIN is able to document a few continental works with engraved illustrations, including Lalla Rookh : ein morganländisches Gedicht, translated by Johann Ludwig Witthaus and published by Schumann of Zwickau in 1822. This work, presumably intended for those with a modest book budget, has but two illustrations, both engraved by one J. Thaeter. We only have the surnames for the two illustrators – Rensch designed a frontispiece of Lalla Rookh, while Baumann designed an image depicting Aliris holding a faint Lalla Rookh after his identity as her beloved Feramorz is revealed. Even more obscure are the identities of the designer and engraver of the frontispiece to volume one of The Works of Thomas Moore, as issued in Paris by Arthus Bertrand in 1820. Depicting the prophet Mokanna unveiing himself to Zelica, this is designed by “Ch” and engraved by “Dx” (see below).

Although lithography — “a printing process that uses a flat stone or metal plate on which the image areas are worked using a greasy substance so that the ink will adhere to them” (tate.org.uk) – was discovered in 1798 (britannica.com), the first known example of this technique being used to illustrate Moore is the 1860 illustrated edition of Paradise and the Peri issued by the London-based firm Day & Son. lllustrator Owen Jones (1809-1874) and illuminator Henry Warren (1794-1879) offer a luxuriously colourful response to this particular tale of Moore’s, a sample of which is produced below.

Images courtesy of Special Collections, Queen’s University Belfast

We conclude this blog by announcing that two electronic collections that will be available through project ERIN’s dedicated website by the end of this month are here given a ‘soft launch’ through their home site in omeka.qub.ac.uk.

Collection number 17, ‘Moore’s Irish Melodies” Texts and Illustrations”, includes numerous still images that document the efforts of the artists mentioned above, as well as others active in London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow in the Victorian era. See also ‘Lalla Rookh in 19th-century Europe’ (collection 15) for 71 images associated with that work. (A third collection, related to the National Airs, is still under development.) All of these collections will be interpreted through OMEKA exhibitions that will become available through the project ERIN website by the end of August 2017.