Guest contributor Conor Browne

Romantic era composer Robert Schumann (1810- 1856) is most likely to be known his numerous lieder. His great interest in literature led him to read Moore’s story of Lalla Rookh. Schumann first came across Moore’s poem in the early 1840s. In a diary shared with his wife, Clara, he declared “Thomas Moore’s Paradise and the Peri has just been making me very happy” (translated Litzmann, p. 328). Schumann then continues by claiming that “something good in the way of music might be made of it”, showing his initial excitement at this prospect. Inspired by Moore, Schumann began to develop his oratorio, Das Paradies und die Peri, with a sustained composition period in the early months of 1843. He wrote this beautiful music in his spare time, as he had a full teaching schedule at the Leipzig conservatory with over 40 pupils. The diary entries are the perfect insight to Schumann’s progress through Clara’s reaction to each new piece of music that he wrote. “The music is as heavenly as the text; what a wealth of feeling and poetry there is in it!” (Litzmann, p. 350) . It is clear that Clara enjoyed the music of her spouse.

For those who may not know the story behind the work, it is this. A Peri, (an angel from Persian mythology) is expelled from paradise. She is told that in order to regain entrance she must bring a gift that is most dear to heaven. The Peri ponders what this could be and makes attempts to bring various gifts. First she brought the last drop of blood from a fallen young hero who died in battle. This was not enough. After this she journeys to Egypt where she acquires the last loving sigh of a lover who died from disease. Again, this was not enough. Eventually she comes across a repentant old sinner who witnesses a young boy praying. She takes a tear from the old man’s face and brings this gift to the gates of paradise. The gates flew open to receive this gift, admitting the Peri once more. It is a rather sweet fairy tale with morality being the core message. Repentance is the greatest gift.

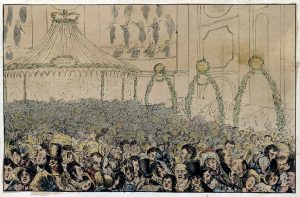

The oratorio premiered in Leipzig on 4th December 1843 and evidently was a rousing success as several repeat performances followed, including Dresden on the 23rd of December and Berlin early the following year. Clara’s diary also records some of the early performance issues that nearly frustrated the work’s premiere, including singers unable to handle the more technically demanding parts. Yet the first audience was attentive , and the press positive. However “Lalla Rookh” was being performed in Germany much before this. Gaspare Spontini wrote a series of tableaux vivant on “Lalla Rookh” for the Berlin royal court in 1821. Furthermore, a translation of “Lalla Rookh” was published in 1839 by the Leipzig-based publisher Bernhard Tauchnitz, so it is quite possible that it was through this that Schumann first became inspired.

The Musical Times contains an article by George Grove which shows a letter written by Felix Mendelssohn in 1844, praising the work of his friend Schumann, in a bid to persuade Ewer and Co. of London to publish the oratorio. “It is a worthy musical translation of that beautiful inspiration of your great poet, Moore” (716). Even though no immediate action was taken, word of Schumann’s Paradise and the Peri eventually spread, so much so that it had made waves across the Atlantic. Clara records that the American Musical Institute in New York was preparing it for performance in late 1847. By 1854 it had premiered back in Ireland at Great Brunswick Street, Dublin in a performance of the Royal Choral Institute conducted by John William Glover. According to Freeman’s Journal the music had been re-adapted to Moore’s original poem for the purpose of this performance. As Thomas Moore was from Dublin himself, we can be sure that “Lalla Rookh” and the tale of Paradise and the Peri would already have been well known in in his home city. The Peri premiered in England in June 1856. That performance was given by the Philharmonic Society for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. By 1869 Victor Wilder translated the work into an opera libretto titled Le Paradis et la Péri, performed in Paris at the Théatre impérial italien. These performances not only show just how successful the work was, but that it changed and evolved from performance to performance, and even inspired new works, breathing new life into Thomas Moore’s beautiful poetry.

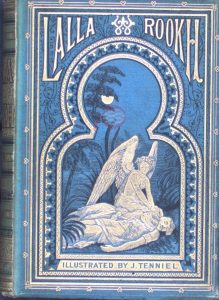

The image shows the beautifully ornate cover page of “Lalla Rookh”, as illustrated by John Tenniel. The Peri is depicted on the cover leaning across the two lovers’ bodies as she takes the last sigh. Image courtesy of Special Collections, McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast.

Works Cited

Grove, George – “Schumann’s Music in England” – Musical Times 47.753 (1905): 716-718. JSTOR.

Litzmann, Berthold – Clara Schumann: An artist’s life, based on materials found in diaries and letters, translated by Grace E. Hadow. 1913. Cambridge University Press, 2014. E-book.