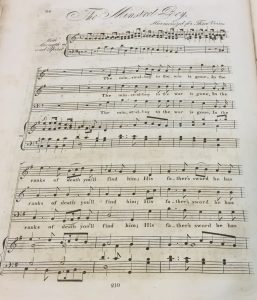

“The Irish Melodies are perhaps the purest national tribute ever bequeathed by a poet to his country” (Novello). While Moore’s achievements were recognised in the years following his death, the efforts of the two composers who provided the original “symphonies and accompaniments” were either derided as too complex (John Stevenson), or ignored (Henry Bishop). And so in 1859, as the copyright to Moore’s Irish Melodies expired, the prominent publishing firm Novello released Moore’s Irish Melodies with new Symphonies and Accompaniments for the Pianoforte by M. W. Balfe. At that time, the well established theatre composer Michael William Balfe was producing works for the Pyne-Harrison Opera Company of London’s Lyceum theatre. The Irish-born Balfe was a logical choice to arrange these melodies — not least given his success as an opera singer before he took up composition and theatre management. In an unsigned preface to Balfe’s edition, the publisher claimed to be responding to a change in public taste “for the simple and natural” by issuing fresh arrangements of Irish Melodies from numbers one through seven. We can appreciate this simplicity in Balfe’s approach to Moore’s ‘Last Rose of Summer’ (Irish Melodies, fifth number), which he sets with single staccato quavers for the left hand punctuating a gentle triplet figure for the right hand of the piano part.

[Audio example to be inserted]

Mezzo soprano Laoise Carney with pianist Brian Connor.

At the same time as Novello was releasing a new version of Moore’s Irish Melodies, so too did the London-based publishers Cramer, Beale and Chappell. Sustaining an earlier interest in the original Irish Melodies (Cramer, Addison and Beale obtained the rights to James Power’s plates for Moore’s Irish Melodies circa 1840), this firm commissioned the London-based composer George Alexander Macfarren (1813-1887) to arrange Moore’s Irish melodies with new symphonies & accompaniments – also restricting the selection to songs from the first seven numbers. Macfarren’s arrangements were further promoted by Cramer through a wide selection of individual songs published into the 1870s; the London-based firm J. Macdowell seems to have taken over this enterprise around 1880. Macfarren’s arrangement of the ‘Last Rose of Summer’ favours a relentless semiquaver figure in the left hand of the piano part, against a purely melodic right hand. His harmonic learning is hinted at in the occasional introduction of a passing modulation.

Granville Ransome Bantock (1868-1946) was another figure who was attracted to Moore’s Irish Melodies. An early recipient of the Macfarren scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music, Bantock demonstrated an interest in Moore while a student there in the early 1890s with his ambitious choral-orchestral setting of The Fireworshippers (see this blog for 30 June 2017). Later in his career, he would arrange some of Moore’s Melodies for voice and piano, including the ‘Song of Fionnuala’ as a song in four parts (1910). Of the three settings considered here, Bantock’s ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ is most successful in evoking the sound of the Irish harp through the use of arpeggiated (rather than rhythmically articulated) chords across both hands in the piano accompaniment.

[Audio example to be inserted]

Mezzo soprano Laoise Carney with pianist Brian Connor.

Reference

Novello. Preface, Moore’s Irish Melodies with new Symphonies and Accompaniments for the Pianoforte by M. W. Balfe. London, [1859].