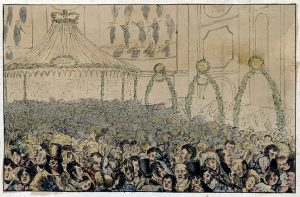

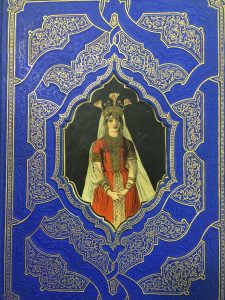

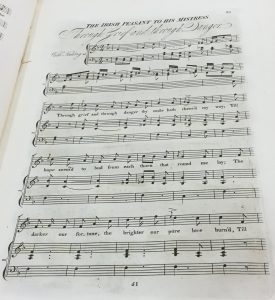

The British Library has a copy of John F. McArdle’s adaptation of Moore’s Lalla Rookh as a Victorian era Christmas pantomime. This work was first staged at the Alexandra Palace Theatre, South Kensington, in December 1883 (and repeated at the Bijou Opera House, Liverpool, 1889). The original production team included Mr C. Brew (transformation scene, the Peris’ Papyrus-Grove), Loveday (music), Mis Guinniss (ballet and processional pageantry), Mr Norbury and Mr Bennett (gas and lime-light effects); Messrs. Knott and Co. contributed the illusions, while Mr Finlay led the team which provided the scenery. In McArdle’s pantomime, the stories of Lalla Rookh and Hinda are intermeshed, with the latter becoming the principal lady-in-waiting to the Mogul princess. As in Moore’s poem, Hinda is beloved by the Gheber Hafed, but he is assigned the role of a pantomime Infernal, along with a new character ‘Khoransabad the Terrible’, who vies with the ‘poet’ Feramors/King of Bucharia for Lalla ‘s hand. Indeed, Lalla’s hand is sought by no fewer than 15 princes and potentates, whose desires are marked in an extended pageant that allows plenty of opportunity to introduce exotic characters (Amazons, Mandarins, and ‘Ashantee Wives’) accompanying the hopeful suitors (the King of Cashmere, the Chinese Emperor, and King Koffee). Lalla Rookh, already totally smitten with the poet Feramors, swiftly rejects them — including Khoransabad, who attempts to woo her with a song to the tune of “Lovely Sally Brook”. She does, however, accept the suit of the unseen King of Bucharia, on the recommendation of the lovelorn Peri Namoune (here two of Moore’s characters are combined as his Namouna was a sorceress in ‘The Light of the Harem’; his Peri was nameless). Namoune has been denied her place in Heaven for daring to love a mortal (Feramors) and can only gain re-entry by effecting the union of her beloved with Lalla Rookh. Lalla’s father the emperor Aurungzebe gives his grudging approval for the match, then sings solo during the Grand Chorus of Moore’s “Let Erin Remember”. The other Peris appear from time to time en masse to sing choruses and perform ballets. The attendant Ghebers, as infernal characters perform an ‘Impish Ballet’, while Hafed and Khoransabad provide a “Grand Revenge Duet”. The Incantation which follows will be familiar : “Double, double, toil and trouble, Fire burn and cauldron bubble” (here described as ‘The Conspirators’ Chorus’). Fadladeen manages to embroil himself in a pitched battle with the impish Ghebers, which Namoune quells by rais[ing] a burning brand and wav[ing] it over them; all fall down, Hafed kneels overawed. In the end, the deserving men (Feramors and Hafed) get their girls, while the ‘baddie’ Khoransabad has to content himself by singing the ‘New Tip-top topical song’ while riding a donkey. The characteristic final appeal to the audience ran thus:

Fad.: With Moore we have made merry; our endeavour

To make the Moore the merrier than ever.

King.: Forgive our follies at this Christmas time,

All’s fair in love and war – and Pantomime.

Nam: Our faults and failings please to overlook.

Lalla: and let no raven crow o’er Lalla Rookh!