Guest contributor Matthew Campbell

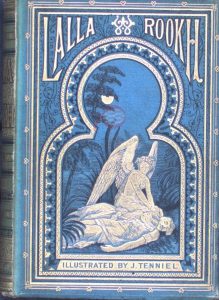

Editor’s note: in May 2017, as part of the lunch series in Music at Queen’s University Belfast, Matthew performed a song as Feramorz from the 1877 cantata Lalla Rookh (W.G. Wills, text, and Frederic Clay, music).*

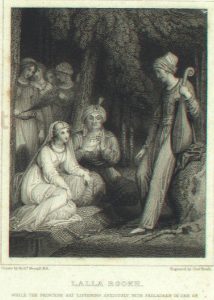

Perhaps a 19th-century Irish poet’s interpretation of the Kashmir Valley may seem far-fetched to students today, particularly as research indicates that Moore had never actually travelled to India in his lifetime. However, his telling of the fictional story ‘Lalla Rookh’ depicts a love story so exotic and beautiful that it really isn’t overly surprising that so many composers chose to realise it through music.

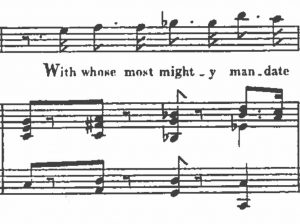

In our snapshot interpretation, I am performing the role of Feramorz and have the pleasure of performing a song from Frederic Clay’s interpretation entitled “I’ll Sing Thee Songs of Araby”. This is a love song which allows me to explore Feramorz character not only as a heroic King in disguise, but also an innocent young man in love.

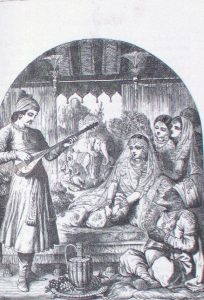

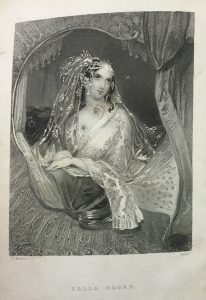

Feramorz sings to Lalla Rookh, as depicted by John Tenniel.

Image courtesy of Special Collections, Queen’s University Belfast.

In Moore’s poem, Feramorz is actually the young King of Bucharia, Aliris, in disguise. He undertakes this disguise in an attempt to woo Lalla Rookh (his intended bride through an arranged marriage) with his poetry and music. Fran Pritchett expands on Moore’s interpretation of the character of Feramorz by writing, “He was a youth about Lalla Rookh’s own age, and graceful as that idol of women, Crishna, such as he appears to their young imaginations, heroic, beautiful, breathing music from his very eyes”.[1] I agree with this depiction as this is somewhat how I myself imagined the character, I would however add that I feel that Aliris’s choice of disguise was more than a cunning plan to woo Lalla Rookh, but rather a genuine act of love suggesting that royalty and riches could not make him happy if he was without the one he truly loved, and his willingness to demote himself of these privileges in an attempt to capture her heart suggest to me that he was more interested in love than materialist wealth and status. When performing as Feramorz I combined these descriptions along with my interpretation of the song to depict a character by implementing simple yet effective methods of characterisation.

My first entrance singing Clay’s song allows me to portray a young man in love as he gazes upon the beauty of Lalla Rookh. By standing up straight with my chest inched forward and my chin raised to allow my head to point upwards towards Lalla Rookh, I can use this body language to suggest a man who is confident and assured, both characteristics of a heroic character. I also interpret this through my gait, which as I move closer to Lalla Rookh is controlled and calm suggesting that I am unafraid of approaching the one I adore. Characterising a young lover is slightly more challenging and in an attempt to achieve this I have opted for subtlety rather than a form of melodrama. Simple extended arm gestures towards Lalla Rookh accompanied by the occasional gaze upon her face should be effective in establishing a form of attraction between the characters.

I also believe that nothing more than subtlety is necessary given the beautiful floating melody of the song, which in itself easily suggests romance. When I sing this song I tend to move a little more rubato than other performances I have heard and this is a personal choice as I believe it allows me to place emphasis on the emotive elements of the song and give it a hint more tenderness and feeling which will also help depict the innocent plea of a young lover. Winton Dean makes an interesting remark in his paper on recitative performance in late baroque opera noting that when singing “not only should there be no regular pulse; there should be no singing in the sense that arias are sung. Recitative was defined as a form of musical speech and should be delivered parlando, not with the full voice”.[2] Whilst I do not feel there are any elements of the song in which it would be appropriate to sing parlando, I do think there is merit in suggesting that the idea is adaptable and therefore also applies to the concept of singing rubato. Young love should not be rigid and restricted and for that reason I would see no benefit in observing every bar line, beat and rest with precise execution. Instead, I would respect the musical integrity of the piece but also give it an element of realism by feeling the mood of the song and adapting my performance appropriately whether that be through change in tempo or dynamics mostly or simply the overall pace of the piece.

When I rehearse Feramorz’s song a natural beauty occurs as I never seem to sing it exactly the same way twice. For this to happen so freely and unplanned is an example within itself of how the song and the character can become one by simply allowing oneself to feel the song.

[1] Pritchett, F (2013) Lalla Rookh (1817), Available at: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00generallinks/lallarookh/index.html#index

(Accessed: 23rd April 2017).

[2] Winton, D (1977) ‘The Performance of Recitative in Late Baroque Opera’, Music & Letters, 58(4), pp. 389 – 402.