There’s a bower of roses by Bendemeer’s stream,

And the nightingale sings round it all day long;

In the time of my childhood ’twas like a sweet dream,

To sit in the roses and hear the bird’s song.

That bower and its music I never forget,

But oft when alone in the bloom of the year,

I think–is the nightingale singing there yet?

Are the roses still bright by the calm Bendemeer?

No, the roses soon wither’d that hung o’er the wave,

But some blossoms were gather’d while freshly they shone,

And a dew was distill’d from their flowers, that gave

All the fragrance of summer, when summer was gone.

Thus memory draws from delight, ere it dies,

An essence that breathes of it many a year;

Thus bright to my soul, as ’twas then to my eyes,

Is that bower on the banks of the calm Bendemeer.

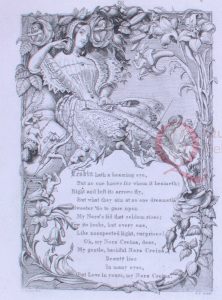

Zelica sings to Azim, drawn by John Tenniel

‘Bendemeer’s Stream’, from ‘The Veiled Prophet’ in Lalla Rookh (1817), is a nostalgic lyric sung by the concubine Zelica to fulfil the prophet’s demands that she seduce her former lover Azim. This individual lyric was set by more composers than any other from Lalla Rookh, with James Power of London publishing settings by Lord Burghersh, William Hawes, and Lady Flint shortly after Moore’s poem came out. A later setting, by Edward Bunnett, was published in 1865. American settings (as ‘Bower of roses’) include J. Wilson (New York, 1817), as well as R.W. Wyatt and S. Wetherbee (Boston, 1820). The song also appears in Charles Villiers Stanford’s opera, The Veiled Prophet (Hannover, 1881; London, 1893 as Il profeta valeto). Project ERIN has recorded a special arrangement of the Stanford (with piano and obbligato clarinet), which will be made available on the project website early in 2019.

Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Queen’s University Belfast