Guest contributor Megan Clay

The piano was invented by Italian Bartolomeo Cristofori in 1709. It wasn’t until the 1740s that it became widely used in Germany, with notable use in Britain dating from the 1760s – about a decade before Moore’s birth. England quickly became a leading centre of piano manufacture with John Broadwood and pianist-composer Muzio Clementi being the main producers (Temperley, page 400). Yet the piano was considered a new experimental instrument and could only be afforded by the upper classes. This created a clear distinction in the music played by professional and that of amateur musicians. The concert scene was thriving, and the piano was used primarily as part of an orchestra or in an ensemble of wind or string instruments, but rarely as a solo instrument. If the popularity of the piano was to increase, there needed to be a domestic market to introduce solo piano into the home.

Even in 1779, the year Moore was born, pianos were still exclusively for elite, professional musicians, and in Western Europe the harpsichord was still at that time more popular. The divide between professional and amateur musicianship gradually broke down, and more rapidly with the sale of amateur pianos and sonatas written for them.

Domestic music provided a need for printing and publishing scores, therefore making printed music cheaper, more plentiful and more accessible. The sale of piano music grew in the years following 1790, and as the quantity of music being produced grew, the quality grew poorer (Loesser, page 251). Few people were skilled enough to play high quality piano music, and simpler solo repertoire was commissioned to encourage piano playing amongst non-professionals. Composers began to recognise this need for more accessible music, distinguishing “grand sonatas” written for serious musicians from “sonatas” written for amateurs (Temperley, page 403). The latter preferred sonatas featuring popular tunes (Temperley, page 402). Composers turned to writing “in favour of the unskilled and uncultured” simply for the commercial value of the works (Loesser, page 251), as there was a high demand – especially in London. Austrian pianist and composer Josef Wölfl, whilst working in London, wrote to the publisher of Härtel magazine in Leipzig:

“Since I have been here, my works have had astonishing sales; but along with all this I must write in a very easy and sometimes a very vulgar style. So much for your information, in case it should occur to one of your critics to make fun of me on account of any of the things that have appeared here. You won’t believe how backward music still is here, and how one has to hold oneself back in order to bring forth such shallow compositions, which do terrific business here.” (Loesser, page 251)

The piano manufacturing business also benefitted from the growing trend of amateur piano playing, as pianos became readily sought after by the public (no longer merely the upper class) for domestic use.

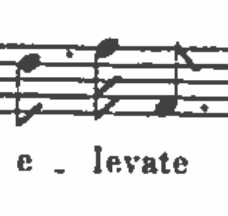

A Clementi square piano, 1829.

“http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piano_3205.jpg” Photo by P.G.Champion, available under a “http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/uk/deed.en_GB” Creative Commons license.

Manufacturers promoted their pianos to amateur musicians and prospective players. In 1810, virtuoso pianist and composer Muzio Clementi (after a successful career as a touring performer), entered the piano manufacturing industry–travelling Europe selling his pianos to amateur musicians. Clementi had fellow pianist Jan Ladislav Dussek, one of the first concert pianists in London (Temperley, page 403), perform his sonatas written for amateurs to mirror the repertory performed in the home and encourage the concept of virtuoso playing there. This was a considerable selling point, as in turn both his compositions and pianos promoted each other (Parakilas, page 26). To achieve this, Clementi created and published an introductory piano book entitled Introduction to the Art of Playing on the Pianoforte (1801) (Parakilas, page 68). His aim was to generate a flourishing piano market so that more people, particularly in the domestic market, would want to learn to play the piano. He also knew that it would be easier to play the piano if one was already competent in harpsichord playing, and encouraged many harpsichord players to convert to playing the piano. Therefore, the previous popularity of the harpsichord can be said to have enabled the success of the piano in the domestic sector.

Bibliography

Ehrlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Loesser, Arthur (1954). Men, Women and Pianos – A Social History. Simon & Schuster, New York.

Parakilas, James (2002). Piano Roles: A New History of the Piano. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Rowland, David.(1998). The Cambridge Companion to the Piano. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Temperley, N. (1981). The Romantic Age 1800-1914. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell.