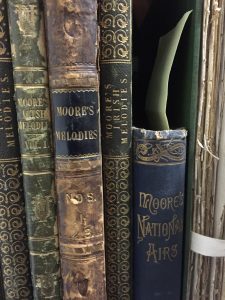

Lalla Rookh is the story of an oriental princess regaled with several fantastic tales by the handsome young poet Feramorz whilst travelling to her own wedding. It is the quintessential romantic epic. Feramorz (Lalla Rookh’s betrothed, the King of Bucharia, in disguise), successfully courts his bride through his story-telling, and so by the time they reach his kingdom he has captured Lalla Rookh’s heart. Moore, who had started writing Lalla Rookh in 1813, began sending it in installments to Longmans of London between March and May 1817. On the 27th of the month it was ‘out’; by December of that year it was in its sixth London edition.

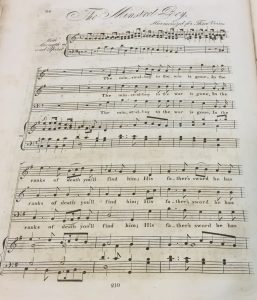

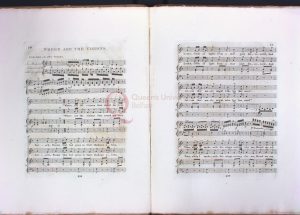

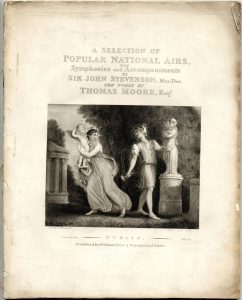

London was also the site of the initial song sheet publications. The poem itself has several song texts, either sung by Feramorz to the princess or sung by characters within the tales he tells. Moore’s regular music publisher James Power issued songs by Dr John Clarke and well as Sir John Stevenson in 1817; this was swiftly followed by settings from Thomas Attwood (4), J.C. Clifton (1), W. Hawes (2), and G. Kiallmark. 1817 also marked Longman’s first edition of Royal Academician Richard Westall’s engraved ‘Illustrations of Lalla Rookh’.

Lalla Rookh continued to stimulate a notable number of vocal and artistic publications, as well as translations of its poetry, up until the first World War. Possibly the first theatre piece inspired by Moore’s poem was Charles Edward Horn’s Lalla Rookh, or the Cashmerian Minstrel to a text by M. J. Sullivan, which opened at Dublin’s Royal Theatre. The next theatrical setting appears to have been Gaspare Spontini’s ‘Festspiel’, Lalla Rûkh, to a text by S.H. Spicker, which was staged at Berlin’s Royal Palace on 27 May 1822. This stimulated a ‘lyrical drama with ballet’ by Spontini for Berlin’s Royal Opera House in 1822, named after Moore’s enchanting odalisque, Nurmhahal. That beauty continued to inspire the German song market, with Carl Maria von Weber setting “From Chinadara’s warbling fount”, otherwise known as the ‘Song of Nurmahal’, by 1826.

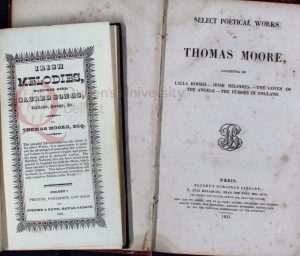

Moore’s Paris agents Galignani included Lalla Rookh in their 1819 English-language edition of Moore’s works; the brothers Schumann of Zwickau issued the first German translation in 1822. Vienna had its own translation, by Baron de la Motte Fouqué, in 1825. In its second decade Lalla Rookh would travel to the orient (literally; Moore reports that the East India Company had named a ship after his creation in 1827); the poem is published in Swedish translation (Turku, 1829), and again in German at Frankfurt-am-Main (1830). Moore’s tale of the hideous (both morally and physically ) ‘Veil’d Prophet of Khorassan’ is translated into Spanish (El falso Profeta de Cora-san, Barcelona, 1836) as well as Italian (Il Profeto velato, Torino, 1838). As the Victorian era advanced, there was a particular emphasis on illustrated editions of Moore’s poem–but that is a tale for another time.

Are you aware of any translations of Lalla Rookh not mentioned here? Please tell us on the blog!