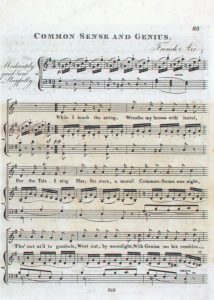

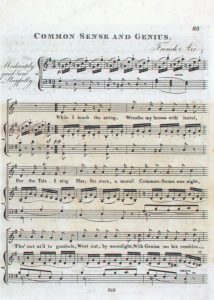

This month of national natal days suggests a couple of blog posts about Moore’s reactions — both as a person and as an artist– to other nations in which he lived. He had a strong connection with France, having lived there for the best part of four years (January 1819-November 1822), during which time Moore recorded his impressions in his Journal. Upon arriving in Paris he secured “a little fairy suite of apartments” on the fashionable Rue Chanterine, venturing to the boulevard theatres the very next day, where he was “much amused”.  Of Spontini’s Olympie at the Paris Opera Moore declared “Nothing can be more poetically imagined than the scenery and ballet of this opera.” After hearing Rossini’s music at a ball, Moore described it as “delicious”, the socialite in him appreciating “the ease with which all Rossini’s lively songs and choruses may be turned into quadrilles and waltzes”. He quickly made the acquaintance of the fashionable novelist Madame de Souza-Bothello, discussing her current romance (novel) whilst it was in progress. With the arrival of wife Bessy and his brood of children, the family moved to a cottage with a garden on the Champs Elysees. Moore swiftly became part of Madame de Flahault’s social circle, singing at intimate gatherings attended by other ex-pats. By May 1820 Moore had a wide social circle that he entertained at home, al fresco with champagne under the trees when the weather permitted. In the summer of 1820 he joined with the rest of Paris in watching various adventurers travel by hot-air balloon, including the ill-fated Mademoislle Garnerin (who was eventually lost on one such voyage). Moore reported a new-found appreciation for “the charms of inanimate nature” on a walk from St. Cloud to Ville d’Avray (this appreciation of natural scenery certainly comes across in some of the Irish Melodies). Although he was underwhelmed by a ball given by the Gardes du Corps at the Chateau of the Tuileries (“not so fine as a I expected”), Moore expressed complete delight with his family’s summer residence in La Butte, declaring “as far as tranquility, fine scenery, and sweet sunshine go, I could not wish to pass a more delightful summer.” He met Princesse Tallyrand at a dinner in May 1821, taking pleasure in her evident engagement with a French prose translation of his Lalla Rookh, as well as her kindness in praising the beauty of his wife; Moore’s uxoriousness was legendary, and he cheerfully reported in his Journal that an acquaintance declared “every one speaks of your conjual attention, and I assure you all Paris is disgusted with it.” The Journal records Moore’s personal impressions rather than his political views, but he tells with sympathy an anecdote he learned of a French Royalist he met, whose young lady was arrested (and subsequently imprisoned for six months) merely for wearing a tricolore ribbon to a masked ball. Initially admiring of Napoleon (“this thunder-storm of a fellow”), Moore described his exile to St Helena as “unsportsmanlike”. Moore was inspired by his Parisian period to write the epistolary satire, The Fudge Family in Paris, which, as Ronan Kelly notes in his Bard of Erin, has “an autobiographical ring” to certain of its details. Moore also featured no fewer than ten French Melodies in his six-volume series of National Airs (1818-1827). Moore’s presence (through publications of his work) in Paris will be charted further through other outcomes of this project.

Of Spontini’s Olympie at the Paris Opera Moore declared “Nothing can be more poetically imagined than the scenery and ballet of this opera.” After hearing Rossini’s music at a ball, Moore described it as “delicious”, the socialite in him appreciating “the ease with which all Rossini’s lively songs and choruses may be turned into quadrilles and waltzes”. He quickly made the acquaintance of the fashionable novelist Madame de Souza-Bothello, discussing her current romance (novel) whilst it was in progress. With the arrival of wife Bessy and his brood of children, the family moved to a cottage with a garden on the Champs Elysees. Moore swiftly became part of Madame de Flahault’s social circle, singing at intimate gatherings attended by other ex-pats. By May 1820 Moore had a wide social circle that he entertained at home, al fresco with champagne under the trees when the weather permitted. In the summer of 1820 he joined with the rest of Paris in watching various adventurers travel by hot-air balloon, including the ill-fated Mademoislle Garnerin (who was eventually lost on one such voyage). Moore reported a new-found appreciation for “the charms of inanimate nature” on a walk from St. Cloud to Ville d’Avray (this appreciation of natural scenery certainly comes across in some of the Irish Melodies). Although he was underwhelmed by a ball given by the Gardes du Corps at the Chateau of the Tuileries (“not so fine as a I expected”), Moore expressed complete delight with his family’s summer residence in La Butte, declaring “as far as tranquility, fine scenery, and sweet sunshine go, I could not wish to pass a more delightful summer.” He met Princesse Tallyrand at a dinner in May 1821, taking pleasure in her evident engagement with a French prose translation of his Lalla Rookh, as well as her kindness in praising the beauty of his wife; Moore’s uxoriousness was legendary, and he cheerfully reported in his Journal that an acquaintance declared “every one speaks of your conjual attention, and I assure you all Paris is disgusted with it.” The Journal records Moore’s personal impressions rather than his political views, but he tells with sympathy an anecdote he learned of a French Royalist he met, whose young lady was arrested (and subsequently imprisoned for six months) merely for wearing a tricolore ribbon to a masked ball. Initially admiring of Napoleon (“this thunder-storm of a fellow”), Moore described his exile to St Helena as “unsportsmanlike”. Moore was inspired by his Parisian period to write the epistolary satire, The Fudge Family in Paris, which, as Ronan Kelly notes in his Bard of Erin, has “an autobiographical ring” to certain of its details. Moore also featured no fewer than ten French Melodies in his six-volume series of National Airs (1818-1827). Moore’s presence (through publications of his work) in Paris will be charted further through other outcomes of this project.

Are you aware of the past-times and impressions of other visitors to Paris during the 1810s and ’20s? If so, tell us about it on the blog!

Are you aware of the past-times and impressions of other visitors to Paris during the 1810s and ’20s? If so, tell us about it on the blog!

Images reproduced courtesy of Special Collections, the McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast.