Picking up on the previous posting by Conor Caldwell, today we will consider further the dissemination of the highly popular tune, “Nora Creina.” Beethoven and Moore appear to have noticed this tune at around the same time, for the former is believed to have acquired it by 1810 (to honour a commission from the Edinburgh-based published George Thomson), while the Moore-Stevenson arrangement of it appeared in Irish Melodies number four of 1811. ‘Nora Creina’ subsequently inspired various transcriptions for piano, including Augustus Meves (London, 1818), William Vincent Wallace (London, 1856), and R.F. Harvey (London, 1872). Its lilting 6/8 metre also made is a popular choice for dance compilations, including Admired cottillions for balls and private parties (Philadelphia, c. 1835), as well as Pop goes the weasel! (London, c. 1850).  With Moore’s lyrics, “Lesbia hath a beaming eye,” the tune was circulated in a small 1814 compilation issued by an anonymous Waterford printer ( held in the National Library of Wales); in 1828 an enterprising publisher in Falkirk issued “Lesbia” as part of Three excellent new songs (held by University of Glasgow Libraries). Continued interest in Moore during the Victorian era saw all of Moore’s Irish Melodies subsequently edited by J.W. Glover ( Dublin: Duffy, 1859), as well as by official copyright holder Francis Robinson (Dublin: Robinson and Russell, [c. 1865]). “Lesbia” attracted at least one additional arrangement, by the London-based composer Alexander S. Cooper (1869). While Lalla Rookh (1817) was perhaps the first of Moore’s works to be issued with numerous illustrations, arguably the most famous of such presentations is the mid-century Longmans edition of the Irish Melodies, with one or more illustrations for each and every Melody by Daniel Maclise.

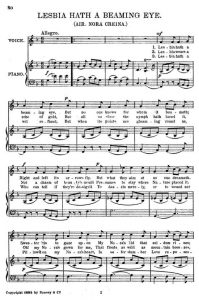

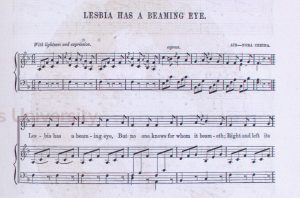

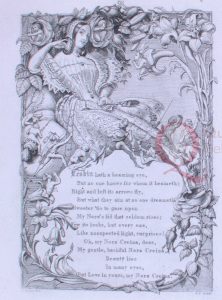

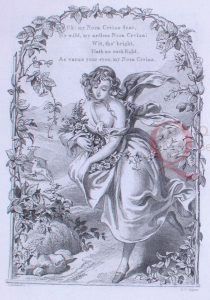

With Moore’s lyrics, “Lesbia hath a beaming eye,” the tune was circulated in a small 1814 compilation issued by an anonymous Waterford printer ( held in the National Library of Wales); in 1828 an enterprising publisher in Falkirk issued “Lesbia” as part of Three excellent new songs (held by University of Glasgow Libraries). Continued interest in Moore during the Victorian era saw all of Moore’s Irish Melodies subsequently edited by J.W. Glover ( Dublin: Duffy, 1859), as well as by official copyright holder Francis Robinson (Dublin: Robinson and Russell, [c. 1865]). “Lesbia” attracted at least one additional arrangement, by the London-based composer Alexander S. Cooper (1869). While Lalla Rookh (1817) was perhaps the first of Moore’s works to be issued with numerous illustrations, arguably the most famous of such presentations is the mid-century Longmans edition of the Irish Melodies, with one or more illustrations for each and every Melody by Daniel Maclise.

The bibliophiles amongst our readers may enjoy tracking the different variants to Moore’s poem, most of which were promoted by the poet himself–perhaps with some unintentional variants introduced by ‘the printer’s devils’ variously associated with music publisher James Power in London. The very opening of the song, initially presented as “Lesbia hath a beaming eye” in both poem and lyrics, first became “Lesbia has a beaming eye” as early as the letterpress poem of the 1813 J. Power edition. While Moore favoured has exclusively from 1815 in his editions with James Power, by the time the London-based Longmans firm issued his Poetical Works (1840-41), he had reverted to hath. We find both these variants (and others with different dates of origin) live and flourishing in posthumous editions of the Victorian era. And also illustrations celebrating the sophisticated charms of Lesbia as compared with the artless appeal of young Nora Creina.

Do you know of editions or arrangements of ‘Nora Creina’ not mentioned here? Do you think they were stimulated by Moore, or another variant of the tune? Tell us about it on the blog!

Images reproduced courtesy of Special Collections, McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast.