By Guest Contributor Daniel Steele

Editor’s note: in May 2017, as part of the lunch series in Music at Queen’s University Belfast, Daniel performed a recitative as Fadladeen from the 1877 cantata Lalla Rookh (W.G. Wills, text, and Frederic Clay, music).

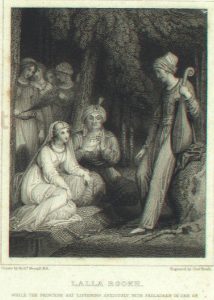

Lalla Rookh, Fadladeen, and Feramors as depicted by Richard Westall and Charles Heath (Longmans, 1817). Image courtesy of Special Collections, McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast.

Lalla Rookh, Fadladeen, and Feramors as depicted by Richard Westall and Charles Heath (Longmans, 1817). Image courtesy of Special Collections, McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast.

Performing a character is always a very subjective affair. The same character may be interpreted and portrayed variously by different people based upon how they perceive the character’s intentions, actions and overall importance to the plot. The presence of effective characterisation, like many things, often goes unnoticed until it isn’t there at all. With the ability to completely alter the way in which an audience perceives and experiences a story-line, effective characterisation is one of the most important aspects of performance in theatre, musical theatre and opera.

The character of Fadladeen is a very complex one. Portraying the ‘Great Nazir or Chamberlain of the Haram’ may at first appear simple as you need only be pompous and commanding in character, but if a fully rounded and three-dimensional character is desired then this simply cannot be the case.

“You must learn to be three people at once: writer, character, and reader.”

(Kress, 2005)

Nancy Kress tells us that in order to become the character, the performer must also become the writer and audience. I believe this means that in the portrayal of a character the performer must consider the writer’s intentions for the character, the character’s own possible intentions based upon the interpreted personality and the audience’s expectations of the character. Doing so allows the performer to tailor their portrayal to be complementary to the writer’s concept, believable to the character (as written) and pleasing to the audience.

A good place to begin dissecting the character of Fadladeen would be to consider Moore’s description of him.

‘Fadladeen was the judge of every thing, – from the penciling of a Circassian’s eyelids to the deepest questions of science and literature; from the mixture of a conserve of rose-leaves to the composition of an epic poem … His political conduct and opinions were founded upon that line of Sadi, -“Should the Prince at noon- day say, it is night, declare that you behold the moon and stars.”’

(Moore, 1817)

This description provided by Moore doesn’t do much to alter the preconceived idea of how Fadladeen should appear or act but rather reinforces the idea of a commanding figure, a man of high stature that commands the stage when he takes to it. Moore does, however, suggest him to be a fiercely loyal character, an aspect which helps to add more depth and possibly context to him and his thought processes.

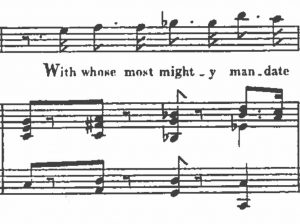

If we take Fadladeen’s first solo recitative from the Frederic Clay (music) and W. G. Wills (text) adaption of Lalla Rookh as an example, we can see that Moore’s idea of character comes through in the rhythmic structuring of the music: a lot of emphasis on the strong beats of the music creates a very commanding feel. This style and ‘feel’ commands the audience’s attention. A frequent use of dotted rhythms in the vocal line helps the performer to understand which syllables should be emphasised as this kind of rhythm naturally creates a more accentuated down beat as seen in fig 1.

The second task to portraying Fadladeen is to consider how he as a character may think and how this effects and helps shape the decisions he makes throughout. We know from Moore’s description that he is a very commanding and loyal figure, but if we study how he speaks and interacts with Lalla Rookh, it isn’t hard to notice that he is also very protective of her–whether this be through fierce loyalty to her father or through compassion towards her, this new dynamic to his character can be vital in the effective realisation of it. Considering his recitative in the Clay adaption once again, when Fadladeen says “Be it my care to wile away thy pain” (to Lalla Rookh), this suggests that he is not simply the commanding figure originally outlined by Moore.

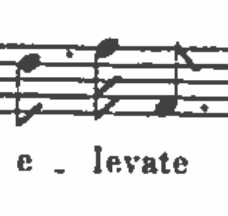

The final task is to consider the expectation of the audience with a figure such as Fadladeen. While Fadladeen has been recognised as a rare English portrayal of a figure who faithfully reflects Persian society (Trench, 1934), it has also been pointed out that he adds a touch of humour to the story (Rao, unknown). It can be found that characters such as Fadladeen usually require even a small bit of humour to keep them from becoming too monotonous. This humour I believe is best found in the small musical ironies within his part in the Clay adaption. As seen in fig 2. Fadladeen sings the word ‘elevate’ as the vocal line drops an octave, an irony that would not go unnoticed by a character, with a capacity to pay such immense attention to detail, such as Fadladeen.

With all these factors considered it is then up to the performer to absorb the information and work out what these different traits mean to them and how that will effect their physical and musical portrayal of the Great Nazir or Chamberlain of the Haram, Fadladeen.

Source List

Kress, N. (2005). Characters, emotion & viewpoint. 1st ed. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books.

Moore, Thomas (1817). Lalla Rookh. London: Longmans.

Trench, W. (1934). “Tom Moore: A Lecture by W. F. Trench.” The Irish Monthly, [online] 62(736), pp.662 – 664. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43651635 [Accessed 9 Apr. 2017]. http://

www.nirupamamenonrao.net/uploads/4/2/6/7/42673355/imagined_journeys_as_pdf.pdf

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00generallinks/lallarookh/part_01.html

Click to access IMSLP286105-PMLP287163-Clay_-_Lalla_Rookh_-_numbers_1-8.pdf