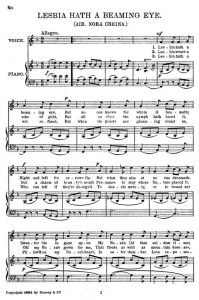

Perhaps the most noteworthy example of Thomas Moore’s impact upon the Irish instrumental music repertoire is seen through the song ‘Lesbia Hath a Beaming Eye’, which is set to the single jig tune ‘Nora Chríonna’ (single jigs are marked by 12/8 time signature and the predominance of crotchet-quaver movement). This simple tune is one of the most collected in the entire Irish repertoire. Thompson collected a three-part version as early as 1755 under the name ‘Ranger’s Frolick’, from which we can see the development of the A part familiar to us today.

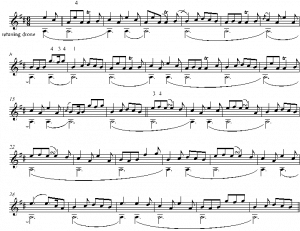

A later version appears as ‘Norickystie’ in James Aird’s A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs (1790-97). It was almost certainly Moore’s song to the air that standardised the melody in 1810, although Capt. O’Farrell’s four-part version (with the C and D parts set as repeats of the A and B parts an higher octave) must also have been prominent. Later versions were also published by celebrated Irish collectors Francis O’Neill and Breandán Breathnach. The following transcription of the tune comes from the playing of the Donegal fiddler John Doherty (1900-1980) and is particularly noteworthy for his use of continuous tonic pedal in imitation of the highland pipes, achieved through the use of open tuning on the fiddle.

A key similarity between Moore’s setting and the contemporary dance tune is the retention of the flattened seventh in bars 11 and 8, respectively, of the Moore and Doherty transcriptions below. This feature is reminiscent of the Gaelic scale system which Moore’s rival, Edward Bunting overwrote in his publications.

Of course the Irish instrumental tradition is defined by more than just renditions of dance tunes. Indeed, instrumental airs form one of the core strands of the modern tradition and a fine example of this is seen in the Dublin fiddler Tommy Potts’s (1912-1988) iconic setting of ‘Believe me if all those Endearing Young Charms’.

These are just two examples of Moore’s wider influence on the musical discourse of subsequent generations in Ireland and beyond. The teaching of Moore’s songs in Irish national schools after the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922 undoubtedly brought them into the consciousness of young musicians. His influence on the oral tradition should be acknowledged, not just in his own time, but in the decades which have followed.