Project ERIN has published forty-one podcasts of individual pieces of music, music either set to words by Thomas Moore or inspired by his work in some way. Today we will introduce the first set within these podcasts, which were taken from a student-based project for the Queen’s University Belfast BMUS module ‘A Night at the Opera’ in spring 2017. Since this was the bicentenary of Moore’s Lalla Rookh, it was decided to recreate this tale through a mixture of narration (written and delivered by the students themselves) and a selection of music, ranging from domestic songs dating from as early as 1818 to the 1893 version of a grand opera. The students provided their own arrangements to these works, sometimes adding an obbligato instrument to a song originally conceived for voice and piano only, sometimes working as a small chamber group to perform a piece originally conceived for orchestra.

Our programme opened with the “Slow March” from Frederic Clay’s cantata Lalla Rookh – originally written for the Brighton Festival of 1877. We used our arrangement of this as an atmospheric piece that recurred to suggest ‘travel’ from one section of Moore’s work to the next. We then followed the structure of Moore’s tale, drawing on Clay again for the song “Princess thy royal father”, sung by Lalla Rookh’s officious chaperone Fadladeen as he supervises that princess’s reluctant wedding journey to meet a groom she has never met. Said groom has disguised himself as the poet Feramorz so he can join Lalla Rookh’s train and court his bride; we recorded the runaway hit of Clay’s cantata, “I’ll sing thee songs of Araby” as the poet’s first – and successful – attempt to intrigue his betrothed. Prior to this, we hear Lalla’s expression of restlessness and lack of fulfilment in “Sous le feuillage” from Félicien David’s opera comique Lalla Roukh (Paris, 1862).This highly popular work travelled across the theatres of Europe, and did much to circulate Moore’s tale to new audiences (for further see project ERIN’s OMEKA exhibit, ‘The tales and travels of Lalla Rookh, at http://omeka.qub.ac.uk/exhibits/show/tales-travels-lalla-rookh/.)

‘The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan’ is the first poetic tale that Feramorz sings to Lalla Rookh in Moore’s original. This dark story of a cult built around a false prophet does not seem to have inspired any domestic songs or cantatas for amateur choral societies to enjoy, but it did stimulate the Irish composer Sir Charles Villiers Stanford to write a grand opera derived from Moore’s work. Within this tale we find ‘Bendemeer’s Stream’ – a mournful reminiscence sung by the prophet’s concubine Zelica to her former lover Azim – from Stanford’s second adaptation of his own work as Il profeta valeto (London, 1983). We offer a unique arrangement of this song for soprano, piano, and obbligato clarinet.

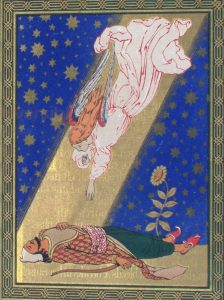

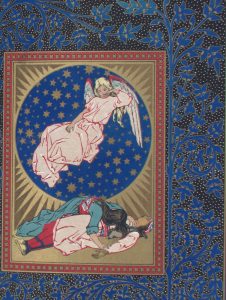

Feramorz’s second tale for Lalla Rookh was ‘Paradise and the Peri’, a lighter but still poignant story of a fallen Persian angel whose desire to enter heaven obliged her to find ‘that perfect gift’. This resulted in the Peri undertaking three quests, from which she brings back: a drop of blood (from a hero), a sigh (from a dying lover), and a tear (from a repentant sinner). We chose music to mark the three recurring actions of this story. Each quest starts with the Peri waiting at the gate of heaven, for which we recorded an arrangement of “Vor Eden’s Thor” from Robert Schumann’s ‘poem in music’ Das Paradies und die Peri (1843). The guardian angel’s repeated refusal to give the Peri entrance is captured by “’Sweet’, said the Angel” from John Francis Barnett’s cantata Paradise and the Peri (Birmingham, 1870). An expression of the Peri’s dashed hopes we also took from Barnett, “But ah! Even Peri’s hopes are vain”. We returned to Schumann for an atmospheric chorus of Arabian maidens, “Schmucket die Stufen”. We concluded our adaptation of this tale with John Clarke Whitfield’s “Joy, joy forever!”, which the Peri sings as Heaven’s gate is finally opened for her. This was taken from his cantata for soprano, The Peri Pardoned; this was published by Moore’s regular music publisher James Power in 1818.

Recordings of all the pieces mentioned above can be found at: http://www.erin.qub.ac.uk/podcasts/. Copies of all the images, with full metadata, can be found at http://omeka.qub.ac.uk/collections/show/15.

Music credits: Oscar Aiken (arranger); Megan Boyd (piano); Courtney Burns (soprano); Ellen Campbell (soprano); Matthew Campbell (tenor); Sarah Coulter (mezzo); Galina Crothers (piano); Jenny Garrett (piano); Ciara Jackson (flute); Jason Jackson (recording engineer); Linzi Jones (violin); Alison Montgomery (piano); Gerard Mullaly (clarinet); Daniel Steele (baritone); Poppy Wheeler (arranger, bassoon, flute).

Part 2 of this blog series will cover the pieces this ensemble recorded from Moore’s ‘The Fire-worshippers’, ‘The Light of the Harem’, and also from the conclusion of Lalla Rookh’s wedding journey.