We are social beings, and relationships are crucial. We need other people to help and support us in different ways throughout our lives, from birth to old age: to take care of us and give us affection when we are babies (but also as we grow up into teenagers and adults), to play with when we are children, to talk to about our worries and our joy, to give us a cuddle when we are upset, to take care of us when we are sick, to have fun and laugh with, to work together with, to give us advice, to show us things, etc. We might often take these relationships for granted, or their importance in our lives, but people experiencing a lack of social support and being isolated in their community are particularly vulnerable to mental health difficulties, financial trouble, offending, and alcohol/substance abuse.

Young people leaving care or who have been in care are more likely to have fewer of these supportive relationships, and that has a huge impact on the quality of their lives. For example, a recent review of the literature found that many care leavers felt that they lacked a “safety net” of support, and relationships with at least some professionals were seen as fundamental in guaranteeing that practical needs were met. Sustained social support from family and/or friends (as well as professionals) is one of the most important issues that appear to influence a variety of outcomes for these young people, in terms of employment and careers, offending, risk-taking, living arrangements, subjective wellbeing and mental health, among others. This is why we will be exploring young people’s relationships with a range of people when we interview them.

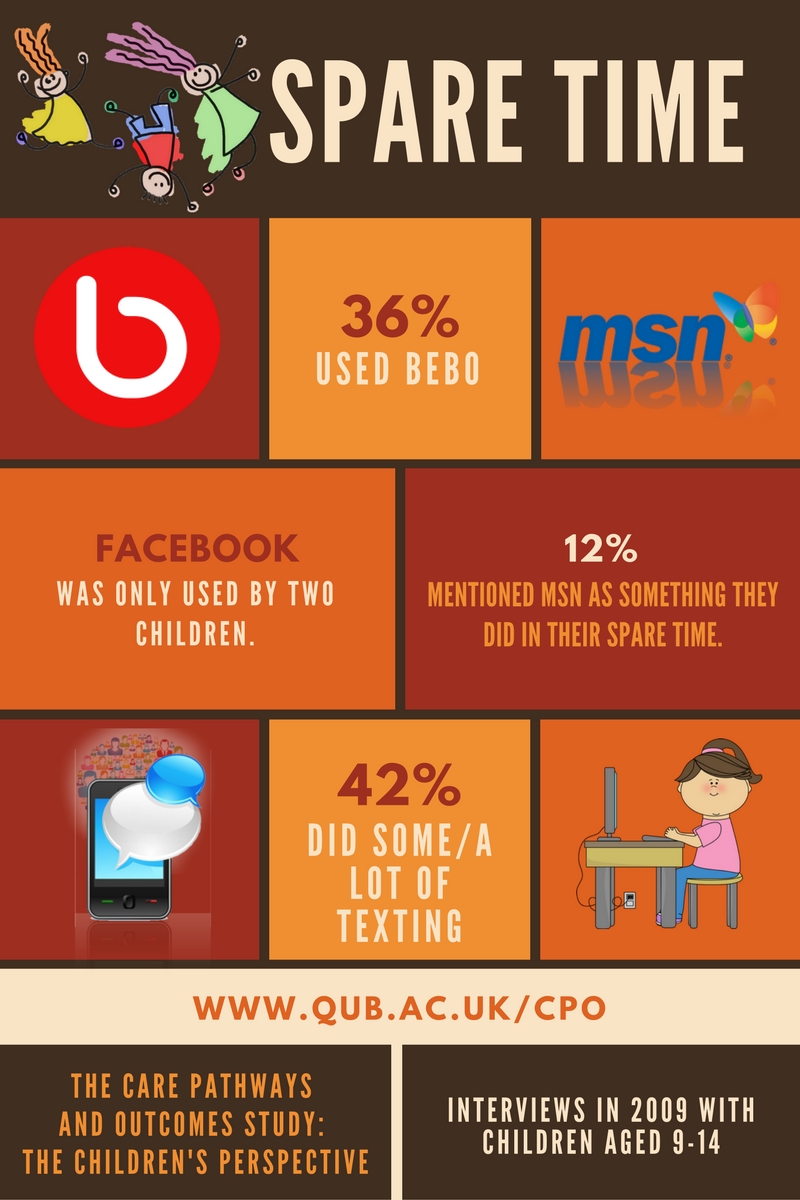

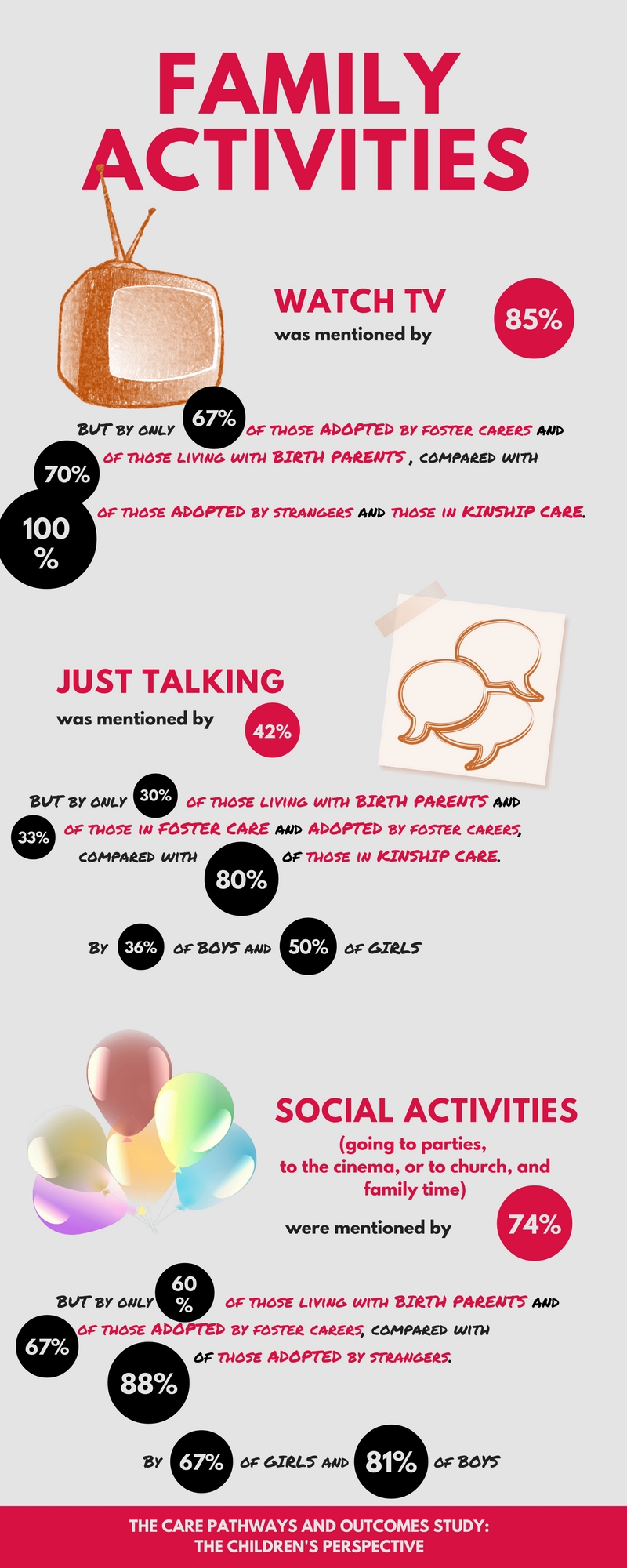

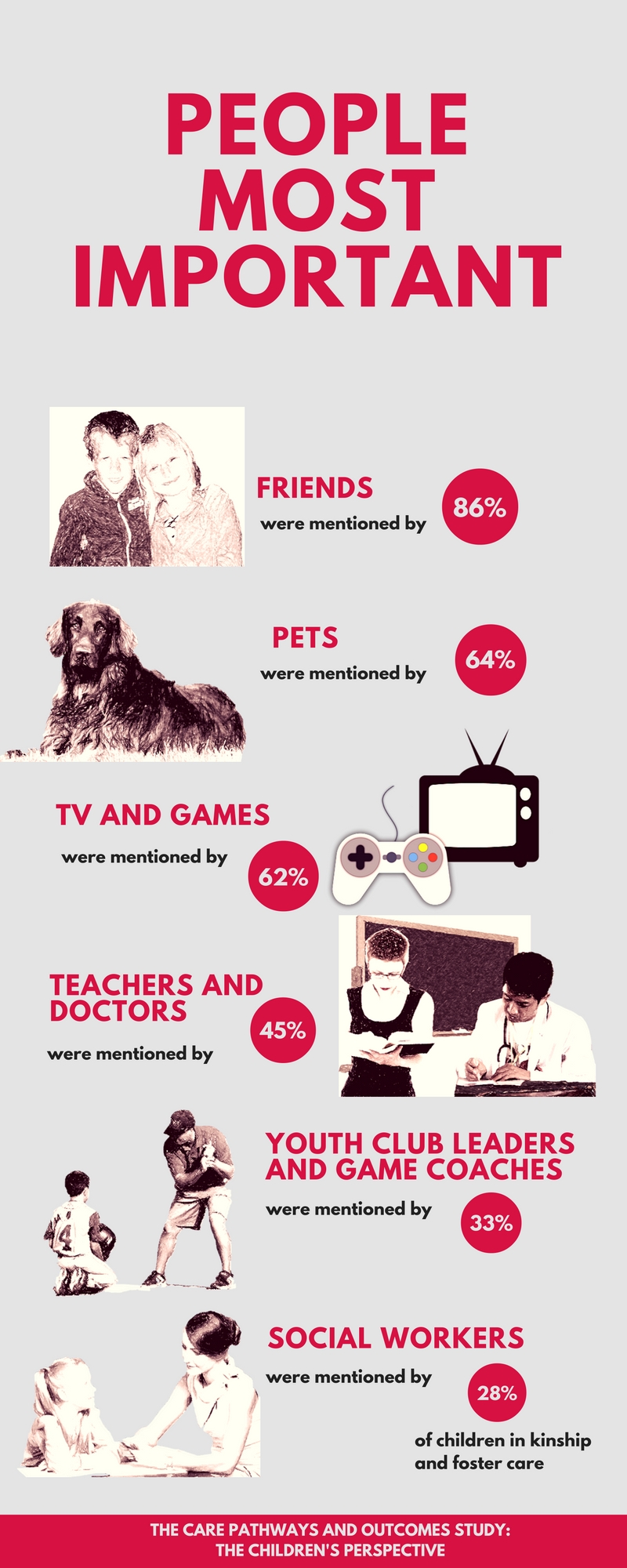

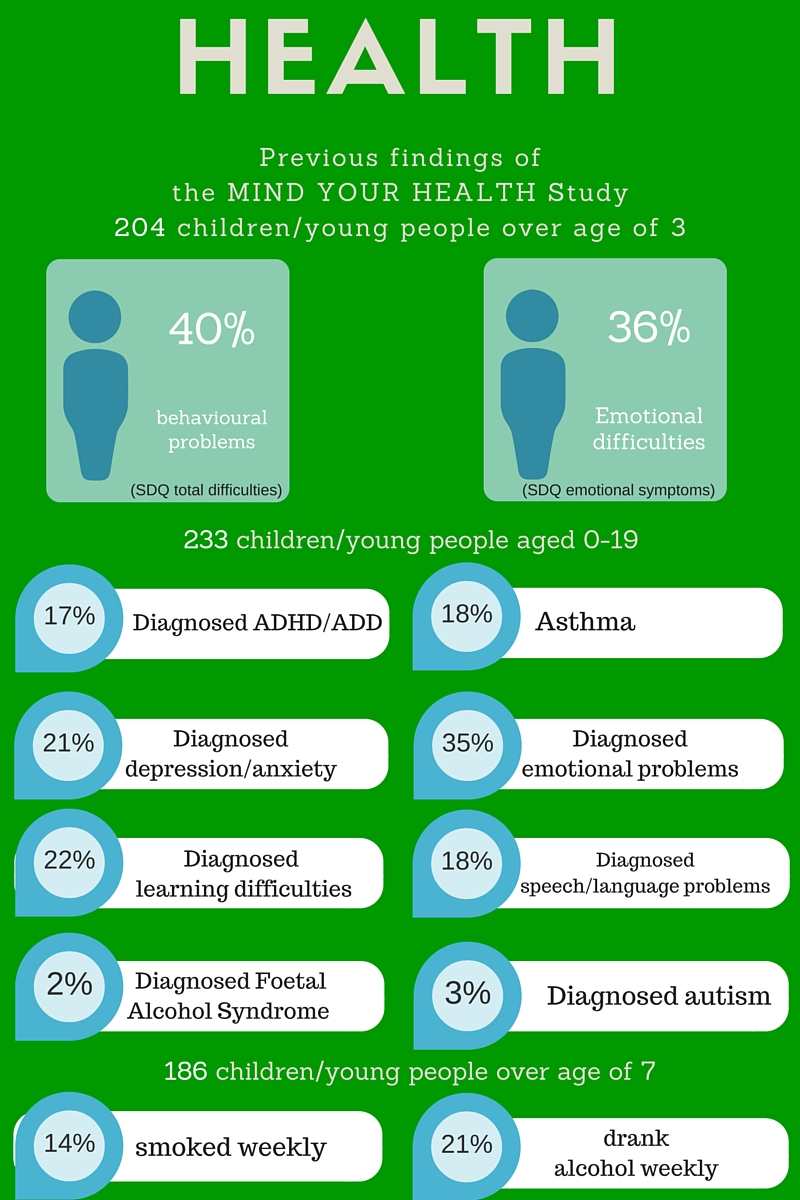

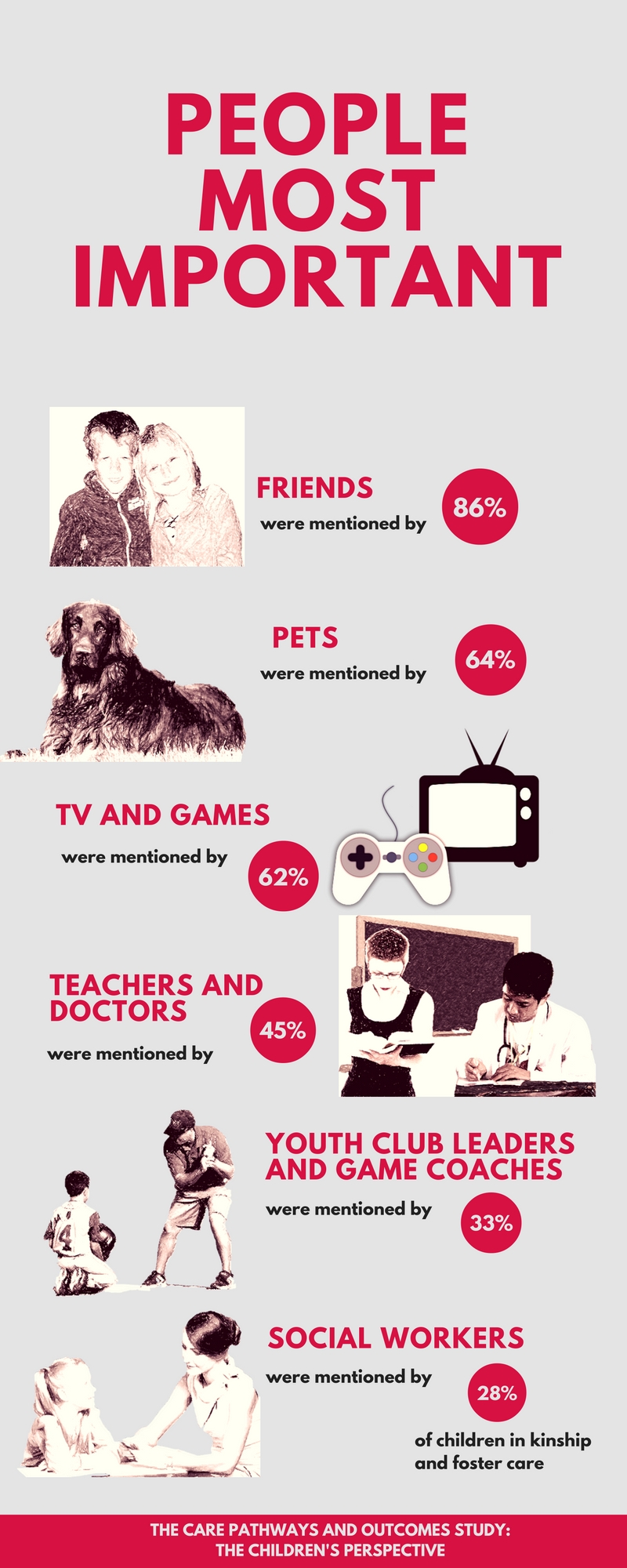

In the previous phase of the study, when the young people were between 9 and 14, we asked them (outside of their families) who was important to them and who gave them the most support. We had different prompts in a book we had especially created with the help of a young people’s advisory group. Young people identified a range of important people, as well as things, including friends, teachers, doctors, neighbours, pets, TV, games, youth leaders, game coaches, and social workers.

Friendships

As children grow into adolescents, they rely less on parents for support, while their relationships with peers become increasingly important when seeking comfort in times of stress. So, as might be expected, apart from their families, the majority of children mentioned their friends (or/and their boyfriend/girlfriend) as important people in their lives. Out of 66 children we conducted semi-structured interviews with, 57 mentioned their friends. Some distinguished between best friends and mates:

“Your best friends, you can tell them like anything, but with your mates, you can’t because they have best mates and they might tell each other” (14-year old girl living with birth father)

The reasons why friends were important to them had to do with their need for communication, companionship, emotional support and play, among others. Here are a few of their responses:

“Because if you lost them, you’d be like… bored, with no friends and… they are into the same stuff as you” (14-year old boy in foster care)

“Because they help me with things. … Well, if there’s something annoying me, I just tell them, or if I’m being bullied I just tell them, or something.” (12-year old girl subject to a residence order)

“Because they know when I am sad and they cheer me up.” (12-year old boy living with birth mum)

“They make me calm like when I’m angry and help me. They play with me and they’re there for me … Like they would talk to me about, like if they see I’m in a bad mood they would talk to me about all the times that what’s been funny about us and then they make me laugh” (11 year-old girl in foster care)

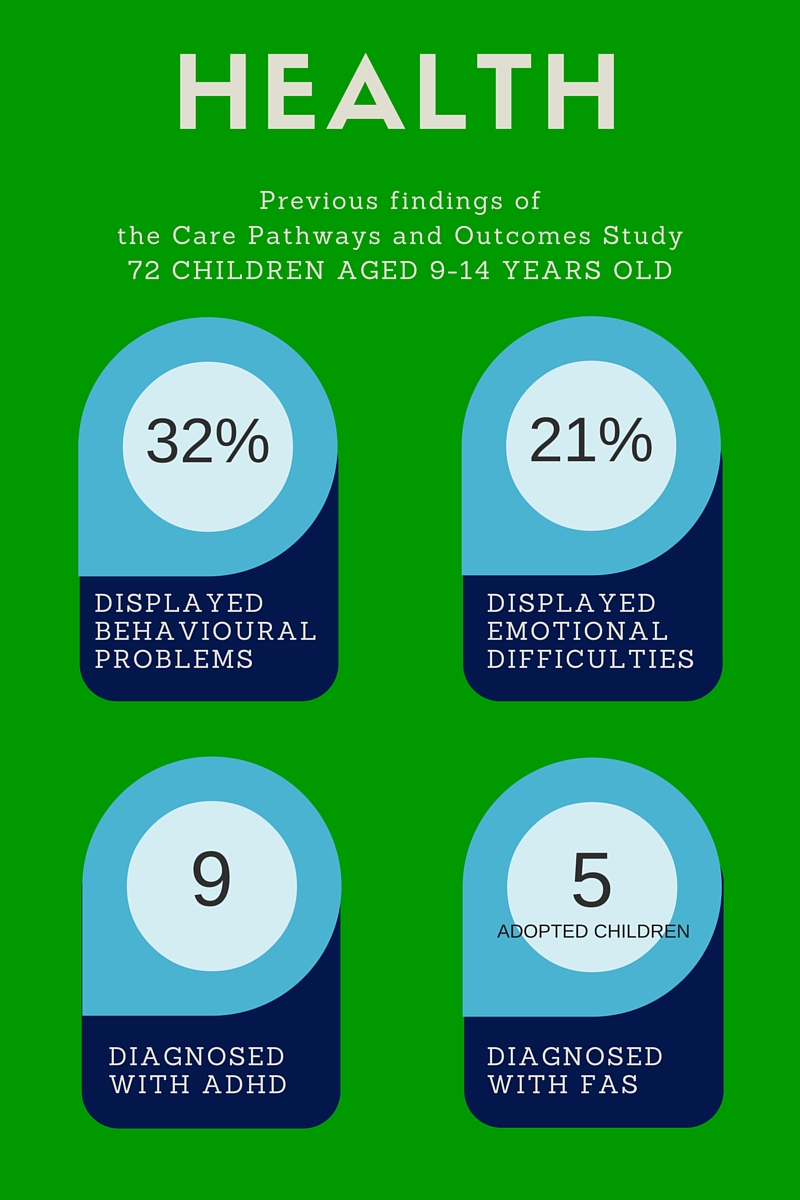

However, there were nine children who did not mention friends. These were children who were experiencing a lack of meaningful friendships. These children were more likely to display behavioural problems (scoring within abnormal range in the SDQ total score) (7 out of 9). A research study found that adolescents with a secure attachment to their peers are less likely to become depressed and anxious than those who are insecurely attached.

Pets

An unexpected finding was the huge importance of pets in the children’s lives. Of the 66 children, 42 said that their pet or pets were important to them. Some even claimed that it was their pet that gave them the most support (apart from their families). These are some of the reasons children gave for the importance of their pets in their lives (which are similar to those given for friends):

“Because when I shout at her, she doesn’t shout back.” (13-year old girl living with birth mum)

“When you’re crying or something, they’d come up and sit beside you and all.” (14-year old adopted girl)

“… every time he sees me, he jumps up … messes around with me” (13-year old boy adopted by previous foster carers)

“… she understands everything … I just tell her stories and she sits there and looks at me as if I have ten heads. … I talk to her all the time.” (14-year old girl in kinship care)

A recent study on the wellbeing of adolescents with disabilities also found that pets were very much an important part of these young people’s lives, and made them feel happy. There is some research evidence on the health, social and psychological benefits of pet ownership, particularly for children experiencing some difficulties (e.g. bereaved, or seriously ill). Our study appears to support some of these findings.

Social workers

A few talked about their social workers being important to them: 3 out of 10 children in kinship care; and 4 out of 15 children in foster care. These children had been able to form good relationships with their social workers, and talked about them being nice and helping them to deal with different issues.

“Because he helps me, like he tells me stuff … [he deals with] important things like does he need to tell mummy stuff and he would go ring her. … He comes out and visits me to see if I’m okay.” (11-year old girl in foster care)

Some of the children explained how they had different social workers. One boy in foster care described these constant changes as ‘annoying’, and an 11-year old girl in kinship care explained how she did not like that:

“I hate them changing because it’s like if you’re watching TV and you can’t find the remote and you wanted to watch something and change, change, change, change…”

This same girl explained why she did not like some of her social workers:

“She was very nosey, snooping about the room. She said she had to go to the bathroom and she ended up in my room looking at my stuff.”

It is clear that social workers have an important role to play in these children’s lives, so it is important that we examine these relationships, and help better understand the positive ways that social workers respond to the needs of children in care.

Relationships in early adulthood

We don’t know who will be important in the young people’s lives as they enter adulthood. Following advice from our consultation events, we will be asking young people about their relationships with significant others, how significant and constant they have been and why, and what positive/negative impact they have had and continue to have in different aspects of their life.