The novel opens with Alix’s harried phone call to Emira asking her to babysit Briar. She calls despite knowing that at 11pm on a Saturday night, twenty-five-year-old Emira is likely to be reluctant to work. Alix utilises their economic disparity as leverage by promising to pay her double and cover the taxi fares.

“It was almost astonishing that Emira’s daily babysitting job […] could interrupt her current nighttime state […] But here was Mrs Chamberlain at 10:51p.m., waiting for Emira to say yes”. (3)

The transitive verb of “waiting” coupled with the incentive of increased pay, highlights Mrs Chamberlain’s expectation – knowing that Emira needs the money, she utilises her privilege to her advantage. Later, the reader discovers the reason for the call is that an egg has been thrown at the window in reaction to Mr Chamberlain’s clumsy speech (32). This domestic “emergency” seems trivial and ironic considering the racist altercation that subsequently occurs at Market Depot.

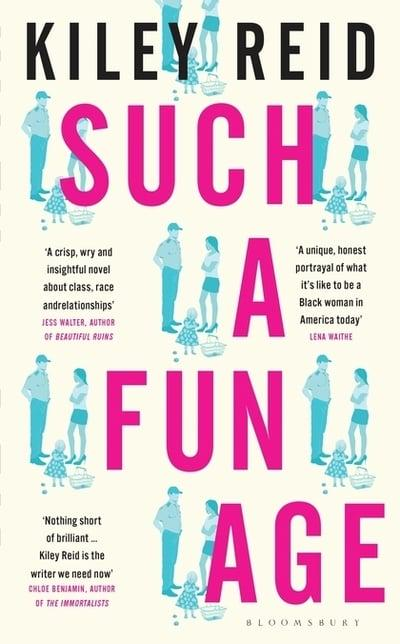

The Standard. Zainab Shafqat Adil The Standard | ‘Such a fun age’ examines subconscious racism (asl.org)

The novel opens with the shocking racial confrontation and accusations of kidnap at Market Depot but, as Berlant writes in Cruel Optimism, “the extraordinary always turns out to be an amplification of something in the works.” (10). This immediately sets a precedent that will occur repeatedly – the white, entitled employer expecting Emira to adapt to her changing whims; from working additional days so Alix can visit her friends in New York (141) or buying a last-minute replacement fish (117). All in a day’s work or taking advantage of her employee?

“And of course you sent Emira to a super-white grocery store, at midnight, and expected everything to be okay.” (228)

The line “And of course” spoken by Kelley sums up the characterisation of Alix. She is “well-heeled, arguably well-intentioned, yet entitled, and ignorant about realities outside her own world.” (Haider). Alix exudes privilege and white feminism; seemingly oblivious to possible outcomes of her actions (Haider). Reid displays this by presenting; on consecutive pages, the racist altercation at Market Depot and Alix’s effortless career progression:

“Alix asked nicely for the things she wanted, and it became a rare occurrence when she didn’t receive them”. (20)

Despite her ability to pay for products, Alix with her marketing degree, expensive stationery and “editorial” image expects (and freely) receives attention and products. Conversely, Emira (predominantly beyond her control) fluctuates between being invisible or hyper-visible.

The novel centres on discussions of perception and constructed selves (Crawford); how we view ourselves, how we want others to perceive us, and the ways in which we present ourselves accordingly. Throughout the novel, Emira’s true personality conflicts with the racially-charged profile that Alix has created around her. This is evidenced by Alix’s surprise at Emira’s advanced vocabulary which to her seems incongruous with Emira’s usual slang and music tastes (79). Alix has created a one-dimensional depiction of how she feels Emira should act. However, even more unsettling is Reid’s exposure of the way the characters relate to themselves (Crawford). This is evident through Alix’s desire to prove herself even in her own subconscious.

“(O)ne of Alix’s closest friends was also black. That Alix’s new and favourite shoes were from Payless, and only cost eighteen dollars. That Alix had read everything that Toni Morrison had ever written.” (139)

The accumulative list coupled with Alix pretending to eat leftovers and “accidentally” having spare food, raises questions of performativity. Her fascination with Emira is one of narcissistic projection – she wants Emira to see the most progressive and (she believes truest) version of herself (Hayes). However, Alix is playing a part, one that she can step away from at any time and continue living her affluent and privileged lifestyle. Alix’s fixation on herself blinds her to seeing Emira as an individual (Hayes). Instead, she only ever views her through the black-oriented lens that she has created.

Slate. Laura Miller. https://slate.com/culture/2020/01/such-a-fun-age-book-review.html

The title “Such a Fun Age” is notable and has three possible meanings (Masad). It could refer to Briar’s toddler years or to Emira as she struggles with the joys and challenges of being on the cusp of independent adulthood (ibid). However, this “fun age” could also be our own contemporary era (ibid). Masad writes that we live in an age which requires “certain people- often those already more vulnerable to exist in specifically politically correct ways while letting others- usually, those with power and privilege- off the hook” (ibid). This is captured poignantly when Kelley tries to convince Emira to release the Market Depot video to shame Alix. Emira refuses, stating, “her life wouldn’t change at all. Mine would.” (193). Emira is aware that Alix’s social status and economic position means that society will never truly vilify her nor the security guard. Instead, despite Emira being there on Alix’s instruction, Emira would be judged as being dressed ‘inappropriately’ or being ‘confrontational’.

Similarly, the ending highlights the legacy of privilege. When Emira unexpectedly observes the family on the street, she does so from a detached distance that was not feasible while working for them (304). She recognises that nothing about Alix has changed – she continues to favour her youngest daughter and exudes entitlement (305). Many years later, Emira still struggles with the impact this privileged upbringing will have on Briar: “if Briar ever struggled to find herself, she’d probably just hire someone to do it for her” (305). Emira concludes; with a hint of bitterness, that life will inevitably come easier to Briar with her inherited privilege and social standing.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism (Duke University Press, 2011). Canvas.

Reid, Kiley. Such a Fun Age (Bloomsbury, 2019).

Secondary Sources

Crawford, Maria. “Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid – a dazzingly clear-eyed debut”. Financial Times. 10 January 2020. Web. Accessed 22 October 2023.

Haider, Arwa. “Such a Fun Age- the hit novel that skewers white privilege”. BBC Culture. 13 February 2020. Web. Accessed 22 October 2023.

Hayes, Stephanie. “Such a Fun Age Satirizes the White Pursuit of Wokeness”. The Atlantic. 8 January 2020. Web. Accessed 22 October 2023.

Masad, Ilana. “Such a Fun Age Is a Complex, Layered Page-Turner”. NPR. 28 December 2019. Web. Accessed 22 October 2023.