The US government ignored prior warnings of the 9/11 attacks, to justify their subsequent Middle East invasions. ‘Climate change’ is a political (particularly Democrat) invention used to garner financial or ideological support. Medical vaccines are poisonous, causing fatal adverse effects, and are thus used to depopulate the earth. US mass shootings are staged performances to enforce gun control laws in governmental attempts to acquire deeper societal control.

These are but a few of the dangerous conspiracy theories that remain popular within twenty-first century discussions, believed by disconcertingly large quantities of individuals.

Many such conspiracies are upheld in America, by groups believing their government to be “…hijacked by external/foreign powers … looking to promote a ‘New World Order’,” whilst holding: “In order to facilitate this [Order] … the government is interested in undermining the power of those who oppose it, by eroding constitutional rights,” (Sweeney & Perliger 54). Throughout his graphic novel Sabrina, Nick Drnaso alludes to real contemporary events that bred conspiracies, also creating his own conspiracy around a fictional murder. In doing so, he profoundly demonstrates the psychological instability of those who promote harmful theories surrounding traumatic events, and the damage they cause to their irrational accepters.

(YouTube)

Within Sabrina, we witness the lives of Calvin and Sandra become harmed by conspiratorial speculations, receiving threats like: “Someone should kill you,” (120) and: “Your address is online[,] … I’m armed and protected. See what happens if they … test me,” (155) as Sabrina’s existence becomes questioned. While each suffer greatly, Teddy (Sabrina’s partner) falls most susceptible to the effects of conspiracy throughout, becoming both a target of the paranoid mob and a succumbing absorber of its deluded mentality.

Someone is at fault. Someone is scheming and capitalizing big time. To … expose the conspirators for the thieving murderers they are; that is my vocation.

Douglas’ Conspiratorial Voice (p.89)

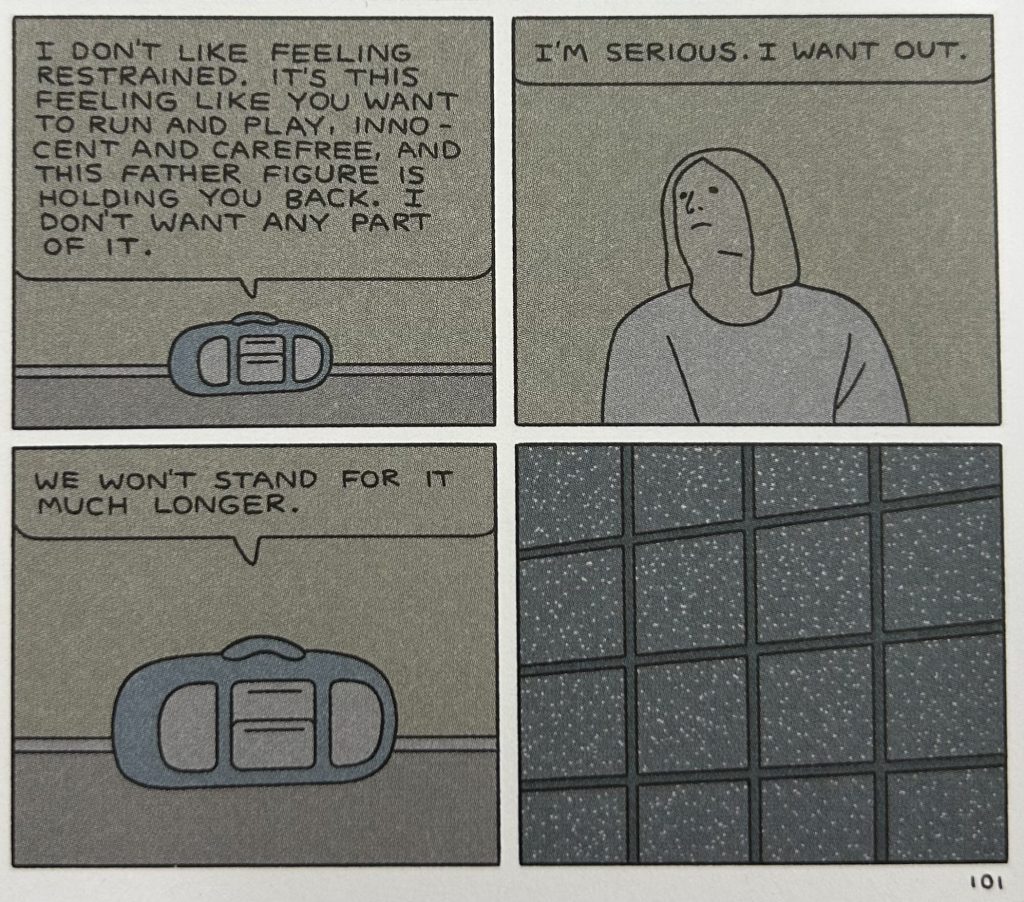

Many conspiracy theories seem “…product[s] of mental illness,” with “…some people who accept [them being] mentally ill and subject to delusions,” (Sunstein & Vermeule 211) which relates to Teddy. Following his introduction, I sympathise with Teddy’s grief-induced sombreness and unwell, dishevelled constitution. His digressions from silence (13), vomiting (37), and nightmares (46) into nervous exhaustion (52) factor into his susceptibility to the neurotic conspiracies of Albert Douglas, voiced on the radio. Douglas characterises an unhealthy conspiracist, discussing “…doomsday predictions,” and “…a global dictatorship,” whilst claiming: “Our masters will flee to their compounds, leaving us to endure unimaginable plagues…” (88). Not coincidentally, such provocative language resembles that of contemporary right-wing conspiracists like Alex Jones and the QAnon movement.

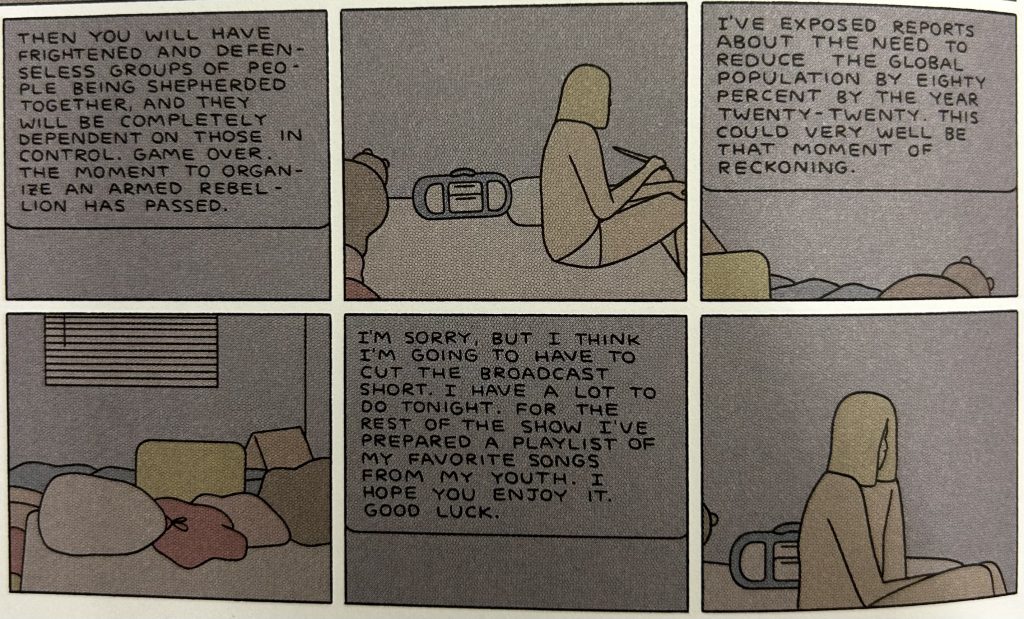

Throughout Sabrina, Douglas’ voice acts supernaturally, being both “…disembodied,” and “…omnipresent,” (Jacobs 72). Ironically, this demeanour transforms Douglas into his worst fear – a malevolent composer that “…stir[s] the pot, to keep [people] separate, suspicious, and hostile,” (88). Relatedly, Oliver and Wood highlight how many Americans “…consistently endorse some kind of conspiratorial narrative about a current political event … [with their] attitudes [being] predicted by supernatural … sentiments,” (953). Such sentiments often revolve around a battle of free humanity against a corrupt, enslaving force, presumably having “…seeds in the fall of the Twin Towers,” (Park §7) highlighted through Drnaso’s allusion to the event. Douglas incites this paranoia, arguing society will have “…defenceless groups of people being shepherded together, and … completely dependent on those in control,” (138) psychologically hauling Teddy into his state of mind. In this sense, Douglas becomes the “…spokesman of the paranoid style,” who “…finds [the conspiratorial world] directed against a nation, a culture, a way of life whose fate affects not himself alone but millions of others,” kindling Teddy’s devolution into a “…clinical paranoic,” that “…sees the hostile and conspiratorial world … as directed specifically against him,” (Hofstadter 4).

Although Douglas claims Sabrina’s murder to “…ha[ve] all the hallmarks of the [routine] staged tragedies,” (108) Teddy remains susceptible to his suspicions. However, notably: “…most people will only express conspiracist beliefs after they encounter a conspiratorial narrative that gives ‘voice’ to their underlying predispositions, assuming the particular incident was unusual … enough to invoke these feelings,” (Oliver & Wood 955) which applies to Teddy. Douglas discusses how he “…[doesn’t] believe … that Sabrina … was murdered by Timmy Yancey,” while posing: “For all we know, she’s alive in bondage somewhere … [or] [m]aybe forces too evil to comprehend did in fact murder [her],” (117) thereby provoking Teddy’s irrationality on two levels. Firstly, Teddy holds onto the possibility that Sabrina is alive, being kept in an area like the referenced “…black site,” (132). On the other hand, Teddy believes that Sabrina’s murder may have been performed by such veiled, heinous figures as described. This highlights the complex nature of conspiracism with trauma, with Teddy’s denial and longing for explanation contributing to his gullible vulnerability.

Eventually, his mistrust peaks, as Douglas’ ‘warnings’ of “…troops … announc[ing] a state of emergency … [and] shut[ting] down the power grid … [thus] keep[ing] the population under control,” (138) take thorough effect, leading Teddy to steal a kitchen knife for protection (135). Thus, through Teddy, Drnaso shows the parasitic nature of conspiracy, particularly within fixated, traumatised, and isolated individuals.

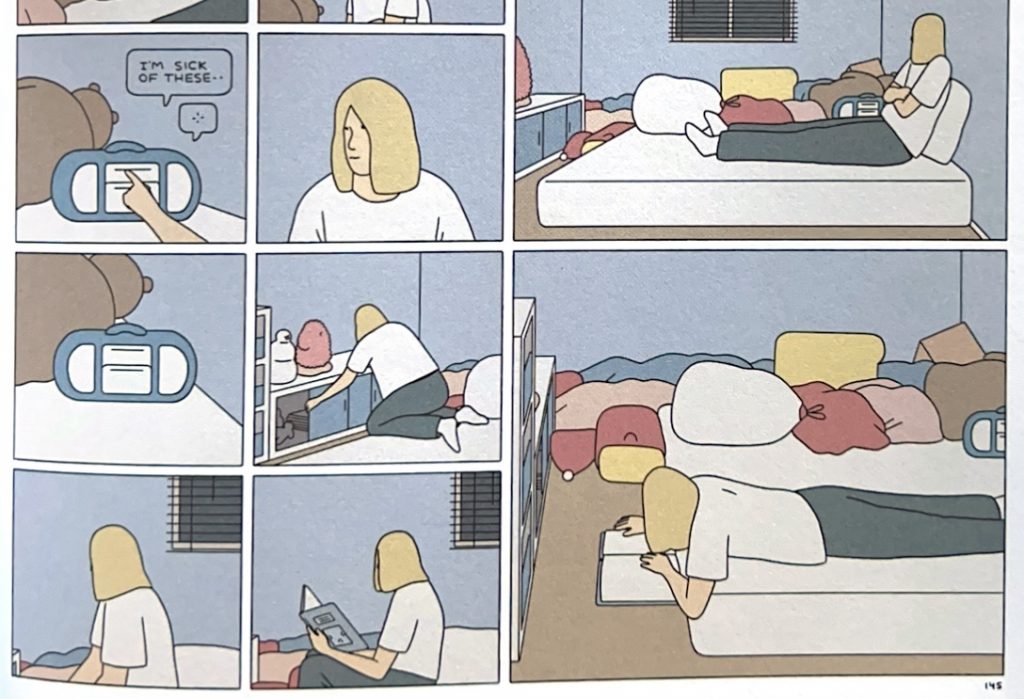

Thankfully, Teddy eventually switches off the radio, and begins reading an academic book designed for children (145). In this humorous implication, Drnaso suggests that there is more educational value in a children’s book than in such ramblings as Douglas’. Despite Teddy’s somewhat contented ending, however, we are left sympathising with those affected by the conspiracy, as Sandra and Calvin remain threatened and isolated, personifying melancholy.

Ultimately, Sabrina warns us to reject catastrophic conspiratorial perspectives, and to instead focus on empathy, rationality, and community. Can empathy be felt for Douglas himself, however? We see remnants of his humanity remain, unashamedly stating: “Thanks for giving me strength, mom. I love you,” (89). Furthermore, he “…served in the army during the Gulf War,” (121) perhaps being similarly traumatised, yet unable to escape the conspiracy cesspit before it consumed him. While this doesn’t justify Douglas’ scaremongering, it certainly sends Drnaso’s ambiguous text into deeper levels of interpretability. Maybe, to avoid being similarly seduced by conspiracies in our volatile contemporary period, we should heed Sabrina’s advice to “…get away from the internet,” (8) and preoccupy our minds with rewarding, satisfactory activities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PRIMARY SOURCE

Drnaso, Nick. Sabrina. Granta Publications, 2018.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Hofstadter, Richard. “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays, Vintage Books, New York, United States of America, 1967, pp. 3–40.

Jacobs, Rita D. “Review: Sabrina by Nick Drnaso.” World Literature Today, vol. 96, no. 6, 2018, pp. 72–73.

Oliver, J. Eric, and Thomas J. Wood. “Conspiracy Theories and the Paranoid Style(s) of Mass Opinion.” American Journal of Political Science, vol. 58, no. 4, Oct. 2014, pp. 952–966.

Park, Ed. “Can You Illustrate Emotional Absence? These Graphic Novels Do.” The New York Times, 31 May 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/31/books/review/nick-drnaso-sabrina.html. Accessed 14 Nov. 2023.

Sunstein, Cass R., and Adrian Vermeule. “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures.” The Journal of Political Philosophy, vol. 17, no. 2, 2009, pp. 202–227.

Sweeney, Matthew M., and Arie Perliger. “Explaining the Spontaneous Nature of Far-Right Violence in the United States.” Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 12, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 52–71.

I really liked your examination of the psychological damage caused by conspiracy culture and how this theme is picked up and developed by Drnaso’s Sabrina – notably the ties between paranoia and mental illness. This seems like very fruitful and exciting territory to explore. Conspiracy is an alternative form of knowledge which in turn denies the basis of any objective or communal basis for knowing the world, including, one must presume, narrative itself. Turning our thoughts back to Sabrina, we’re encouraged by Drnaso’s image-text to see the world through a paranoid lens, where threats are ubiquitous (and to think about how genre encourages such a logic – this is the way we ‘read’ Drnaso’s image-text). But he also wants us to speculate on the damage this causes, exactly as you say, and how we might be able to see through this mode of suspicious reading. Perhaps by seeing it we reduce its effectiveness? One final thought: is it trauma Drnaso is most interested in exploring or perhaps grief? And what might the difference between grief and trauma be? Perhaps grief is something ongoing that we are compelled to live with and that can never be fully resolved.

Thank you for your comment, Andrew. I like how you’ve defined ‘conspiracy’, and, in terms of Sabrina’s narrative and image-text, I initially found myself rather sceptical of Teddy’s character due to his appearance and behaviour (I suspect I am not alone in this). However, as we find out, he is innocent, and utterly traumatised by the event of losing his partner. As you highlight, this where Drnaso’s text initially becomes particularly exhilarating, as the reader becomes the paranoid spectator, constantly on edge for narrative twists, wondering who will unexpectedly be found guilty (likely due to our conditioning by mainstream cliché crime television shows and novels). As we find out, however, this is not Drnaso’s aim, which is perhaps why we are so deeply affected by the somewhat mundane narrative – we feel genuine trauma and grief resonate over the lives of the characters due to the piece’s more personal and realistic approach. Which leads me onto your final point – I believe Drnaso wishes to prioritise demonstration of grief over trauma, as his way of reminding us how to prolongedly ‘feel’ again. I don’t wish to generalise, but I believe we have become desensitised to similar news stories due to the frequency of their occurrence, and we rarely think about the grief which they cause to all involved for overly long periods of time (often to preserve our own sanities, granted). Drnaso’s text thus gives us time to reflect and grieve alongside its characters, showing us, as you say, that grief never ceases for bereaving families, whether we forget about the victims of heinous crimes or not. Trauma around death, on the other hand, is merely a product resulting in grief, with grief often being the ultimate form of psychologically processed traumas. Thanks again for your beneficial response!

I really enjoyed your interesting post which sheds light on some intriguing ideas on the capacity of media to encourage paranoid thinking. You confront the ways in which the radio can be employed as a tool of radicalision. As you point out, in Sabrina, this is achieved by Drasno’s representation of a radio talkshow run by Douglas – an Alex Jones-like figure. Drasno’s graphic novel not only warns about the spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories through traditional media however, but it also highlights the dangers of new media, namely, the internet. As you aptly suggest in your conclusion, Drasno issues his readers a warning to “get of the internet”. Indeed, the the story of Sabrina’s murder is mostly communicated to the reader via online media headlines. To this extent, we are placed in the same postion as Drasno’s characters – rendered equally susceptible to disinformation and radical thinking. The man who offers Teddy a ride towards the end of the novel, for example, becomes a figure of suspicion to the reader who has effectively been conditioned by this constantly paranoid style of information dissemination. In this sense then, the readers themselves, like Drasno’s characters, become conspiracists.

Thanks for your comment, Amy. I wholeheartedly agree that Drnaso’s representation of the internet is almost thoroughly negative, as the author demonstrates the catastrophic effect which social media can have over the lives of those receiving anonymous threats. This is why I feel particularly sympathetic towards Calvin, as his personal life and psychological stability are torn apart during such an instance. While Calvin is a frustrating character in myriad ways (particularly in his emotional unavailability), he is potentially the most rich when it comes to analysis. For example, why does he lie on the psychological evaluation sheets? I presume this is Drnaso’s way of hinting at the toxicity of Calvin’s heavily masculine-dominated military workplace, where one must be stern and macho to survive without ridicule, as well as psychologically stable to remain employed. Furthermore, the tense conversation between Calvin and his co-worker applies to your discussion of paranoid reading, as we are left unsure whether Calvin really is “…paranoid,” (184) or whether his co-worker is associated with the abuse which Calvin has been receiving online. Thanks again for your response, it is incredibly helpful!

I really enjoyed this blog post and was particularly interested in how you likened the character of Albert Douglas to right-wing conspiracist Alex Jones. I specifically liked how you complicate the reading of Douglas as a character by introducing the line from page 89: ‘Thanks for giving me strength, mom. I love you.’ When I came across this line in the novel, my own reading of the character definitely shifted: as you said, Drnaso highlights the character’s humanity and evokes the reader’s compassion for him. I think this speaks to the toxic, polarising and impersonal nature of social media, where individuals online tend to view events and people in ‘black or white’/’good or bad’ terms, and thus find it easy to vilify individuals. In this way, our engagement with social media encourages us to think without nuance, complexity or, even, compassion for those on the other side of the screen. This of course works both ways; for Alex Jones-type characters like Douglas, as well as the likes of Sandra, the victim of tragedy. I think that Drnaso might have been trying to tease this out in pages 153-155 also, where Sandra reads out the online messages she’s recieved. We, as social media users, and likely the audience in the cafe, have probably witnessed some form of oline berating or attack and yet hearing such messages being read aloud is completely unnerving and uncomfortable. The act of reading these messages out loud bridges the disconnect between social media and reality. It makes all uncomfortable because all must acknowledge the fact that there is a human at the receiving end of such messages. You sum it up well at the end of your post by suggesting that this gives Sabrina ‘deeper levels of interpretability’ and acts as a warning to avoid being ‘similarly seduced’ into toxic and polarising modes of thinking, regardless of where you stand on such issues.

I appreciate the response, Emily. I am glad to hear you somewhat share in my potential sympathy towards Douglas, as I expect this to be a rare perspective (however, as you are aware, this is not to say that he can be forgiven for his textual behaviour). I absolutely agree with you on the polarising nature of social media, and believe that one’s tolerance for a difference in opinion has drastically decreased, particularly within the last decade. Relatedly, I think Drnaso’s text shows us the superficiality of many of our ‘issues’ through its representation of such genuinely traumatic events as 9/11 and American school shootings, demonstrating to us the worthlessness of many trivial contemporary ‘problems’. Your final point about our awkwardness around listening to trauma confessions or emotional issues is excellent, a point which once again shows the internet to be thoroughly detrimental in its removal of our ability to sympathise without dissociating as we are prone to. The silence in the room once Sandra reads out some of the messages she has received is very telling, and, notably, following this expectedly cathartic act, she tells her partner that she does not feel any better (155-6). This is likely due to the lack of emotional response she received, leaving her feeling as if average members of society were no longer capable of being compassionate (unless they have experienced something similar). Thanks again for your detailed comment, it will benefit my further reading massively!

I’m actually putting my finishing touches to my essay, and decided to return to your post for some inspiration about discussion around conspiracy theories. I particularly really like the way that you’ve grounded discussions of conspiracy in Sabrina within the real world, and the way you’ve also explored the mental reasoning and theorising behind such actions. I’m also really interested by the emphasis you have given Douglas as a character – I never gave much thought to his role in the narrative, but I particularly am intrigued as to how you discuss him as a potentially empathetic figure. I think especially in today’s age of conspiracy theories it’s incredibly easy to overlook the people behind these ideas as moustache-twirling villains, but paired with your psychological exploration of conspiracy theorists, and approach Douglas as a nuanced character, I’m very drawn to these ideas, and has genuinely made me reconsider Douglas as a more pivotal character within the narrative of the book.

Thank you for your comment, Jack. I hope my brief analysis was beneficial in some way. I definitely think our reading of Douglas is shaped by his disembodied nature, which gives him an air of being deific and omnipresent, thus adding to our suspenseful fear of him and his armed listeners. However, as you say, this just adds to the perception of him as a ‘moustache-twirling villain’, whereas he may just be a young man that has been similarly led astray (as Teddy almost was) and therefore deserves our equal compassion. This does not forgive some of his behaviour however, as he incites violence and delusion, fuelling the mental illnesses of people like him (whose numbers are increasingly rising alongside the growth of anonymous social medias), with Drnaso proving that such voices must ultimately be silenced to preserve the sanity of the public. Thanks again, I greatly appreciate your response. Your blog post was excellent (I didn’t comment as I wished to restore balance to some which were not so heavily responded to), and I am sure your essay will be equally innovative, if not more so!

Thanks James, you’ve definitely given me some food-for-thought with your points made about Sabrina!

Great post James. I’ve always been interested in conspiratorial thinking and how it seems to be endemic in American society in particular. I think you picked up on something key with Douglas’ service in the Gulf War. It definitely has a relation to the beginning of the modern militia movement in the US which dominates American conspiracy theories about a New World Order and a one world government. Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber, served in the Gulf War and he was obsessed with the government ‘encroaching on freedom’, and lots of the original militia members in the 1990s were also Gulf War veterans. I think there’s definitely a connection to be made between the ever increasingly militarised nature of American society and the prominence of conspiracy theories. Your reference to Oliver & Wood about how people are drawn into conspiracy theories when a conspiratorial narrative gives ‘voice’ to their ‘underlying predispositions’ is definitely an important aspect of it, not least for Teddy in Drnaso’s text. I’m thinking specifically about the long history of conspiracy theories in U.S. history and their often very political character. It goes as far back as the Anti-Masonic Party founded in New York in 1828 – a whole political party which was set up to fight ‘Freemasonry’, founded by prominent NY politicians. In that case it was became a vehicle for right-wing politics and embodied a lot of anti-elitist sentiment in NY at the time. Fascinating post.

I loved your examination of the psychological damage, especially the paranoia, caused by conspiracy culture. I think particularly about the physical spaces we see in the book and how they can be a reflection of the characters minds. The interiors and the exteriors, the places Calvin goes too and visits – the relationship between character and space, the consistent emptiness and bleakness of mundane detail. The spaces are empty and cavernous. The apartment the beginning is completely devoid of personality – it’s entirely empty and almost exactly the same at the end when he “clears out” his stuff.