Laoise McWilliams

‘Who am I? And how can I be that person?’

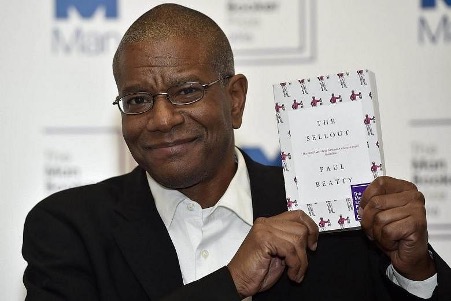

These two questions form a central motif in Beatty’s 2015 The Sellout sustaining an interrogation into identity throughout the novel. The narrator, Me or Bonbon, is introduced to the soothing nature of the questions by his father a psychologist sent to get a ‘psychotic motherfucker to lower his gun.’ His Father’s voice had ‘a way of relaxing the enraged and allowing them to confront their fears anxiety free.’ Beatty similarly employs a soothing authoritative voice to delve into key issues facing Black Americans in a ‘post-race’ society through his use of humour. By embedding humour into the fabric of the novel Beatty offers a dynamic narrative reflective of multifaceted nature of humans and emphasising societies unwillingness to substantively address race issues. In the prologue of the novel Bonbon on trial in the Supreme court states:

‘Your honour, I plead human.’

His objection to the binary negotiations of guilt instantly shatters ideas of typical human nature. He is neither guilty nor innocent with the simplistic and honest style of language imbuing the scene with a theatricality and humour. Naughton argues that by pleading human Beatty questions ‘the universalist ideal of an ordinary and irreducible humanity underlying and legitimising legal definitions of phrases like “human rights” or “crimes against humanity”.’ What we mean by human and an overarching sense of identity is presented as futile and exclusionary as the terms do not reflect Bonbon’s reality. Furthermore, the typical trappings of identity are stripped of Bonbon as he explains:

‘Like the entire town of Dickens, I was my father’s child, a product of my environment and nothing more. Dickens was me. And I was my father. Problem is they both disappeared from my life, first my dad, and then my hometown, and suddenly I had no idea who I was, and no clue how to become myself.’

The consumptive and encompassing language propels the notion that the grounding features of identity, place and family, are denied Bonbon and the population of Dickens. Markers of home and safety are usurped continually leaving the inhabitants in a state of identity crisis. Who they are is lost and progression doesn’t exist within typical linguistic terms. Beatty has created a framework to allegorise the experience of Black people as ‘notions of human identity itself as universal or unchanging may be recognised as a historical construct constituted by the exclusion, marginalisation and oppression of racial others.’ (Bennet & Royle) If Black identity is not included in universal ideals Beatty is pinpointing the failure of language and the repercussions of a loss of identification and belonging.

As a response to being ‘exiled to the netherworld of invisible L.A communities,’ Bonbon draws a border around the town. Through his diagram on his ‘empowerpoint’ he writes binaries such as:

‘WHITE AMERICA / DICKENS,’ ‘THE HOOD / NO MATTER HOW MANY TIMES REFERRED TO AS THE HOOD – NOT THE HOOD,’ and ‘THE BEST OF TIMES / THE WORST OF TIMES.’

Beatty is pinpointing the essential differences between the black community and the surrounding neighbourhood and deliberately portraying black life as a place in opposition to those around it tapping into stereotypes and tropes created by a white-centric narrative. However, he does so through humour and with a creative playful tactic. Beatty himself asserts that ‘Humour is vengeance’ to satirise or mock the harsh reality is presented as an affective form of rebellion. The essential humour does not distil the seriousness of the content as even Bonbon reflects ‘I was more serious about this than I thought’ and felt that the border invoked an ‘implication of solidarity and community’ even though ‘it was just a line.’ The border offers a space of control and importance, it invokes a sense of belonging which whilst humorous it re-establishes a sense of community. Similar to the relaxing tone Bonbon’s father used to ‘make the client feel important, to feel that he or she is in control of the healing process.’ Bonbon’s border is a psychological tool to help rebuild identity compounded by humour that exemplifies the rage and sense of loss experienced by Bonbon.

At the end of the novel Bonbon reflect that ‘Silence can be either protest or consent, but most of the time it’s fear.’ Whilst throughout the novel Bonbon focuses primarily on external markers of identity such as mottos, borders, and signage he distils fear through the use of humour. The novel concludes with Bonbon explaining:

‘I’ve whispered ‘Racism’ in a post-racial world.’

And in doing so ironically ‘managed to racially discriminate against every race in the world all at the same time.’ The act of whispering correlates with soothing, he exposes the fragility of societal structures and the ideological delicacy of America and the fault lines hindering identity and belonging. In doing so Beatty fulfils Frank Wilderson III’s request for ‘something that celebrates the absoluteness of rage’ yet this rage is presented through calming terms and humour. Beatty reflects on the rage and loss by using his humour as a form of vengeance he writes ‘if an increasingly pluralistic America ever decides to commission a new moto, I’m open for business.’

Bibliography:

Aaron Robertson, The Year Afropessimism Hit the Streets?:A Conversation at the Edge of the World, 27 August 2020

Beatty, Paul. 2016. ‘The Sellout.’ (Germany: Oneworld Publications)

Beatty, Paul. 2008. Hokum: An Anthology of African-American Humor. (United States, Bloomsbury Publishing)

Bennet, Andrew & Royle, Nicholas. 2016. ‘An Introduction To Literature, Criticism and Theory’ (Oxon: Routledge

Gerald David Naughton. 2023 “‘Pleading Human’ in Paul Beatty’s The Sellout”, Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 64:3, 443-452, DOI: 10.1080/00111619.2022.2047879