A history of racism in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (2014)

In 2017 the #MeToo movement was booming across social media, following the onslaught of allegations against film producer Harvey Weinstein. Many big-name celebrities came forth online to share their own stories and show solidarity in the face of sexual abuse, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Lawrence, and Uma Thurman to name a few. American actress Alyssa Milano encouraged the use of the hashtag in October 2017, writing that ‘If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote “Me Too” as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem’. With such big stars leading the movement we now, six years later, associate #MeToo with Hollywood.

However, the #MeToo movement was actually birthed on MySpace in 2006 by activist Tarana Burke, an African American woman who used her own history of sexual violence to support and empower other young girls in marginalised communities. Despite receiving accolades from Time magazine as a female activist and ‘silence breaker’ in 2017, Burke’s name and intention has been lost among the names and stories from (predominantly white) Hollywood stars. Only a year later, Burke claimed that ‘The No.1 thing I hear from [black, Hispanic and Native American women] is that the #MeToo movement has forgotten us.’ She added, ‘We are the movement, and so I need you to not opt out of the #MeToo movement…Stop giving your power away to white folks’ (qtd. in Riley, usatoday.com).

‘We are the movement …

(2018)

Stop giving your power away to white folks.’

Christelle Ram uses Burke and the #MeToo movement as a key example in her essay, ‘Black Historical Erasure’ (2020). Ram broadens out the affair by reminding us that ‘The #MeToo movement was partly inspired by the widespread sexual violence experienced by slave women and men’ (25). Here, Ram asserts that sexual violence is inherently a racial issue, having roots in slave history as a ‘tool of violence and dominance’ (26). The erasure of black voices amidst the 2017 #MeToo movement therefore displaces both the history of the movement and the individuals it was made for. The slave women who endured this violence lacked the agency to have ‘their narratives or stories reported or recounted’ (26); the black, Hispanic and Native American voices of the #MeToo movement in this seemingly ‘post-racial’ society have similarly had their narrative and stories usurped by the affluent white voice.

The 2017 #MeToo movement took place three years after the publication of Claudia Rankine’s book, Citizen: An American Lyric (2014), and yet the events of the movement speak to the themes explored in Rankine’s book. Her lyric is concerned with issues surrounding memory and erasure, as well as the body and violence. As early on as page 7, when describing a racial ‘slippage’ between two young close friends, Rankine writes that ‘your fatal flaw [is] your memory’. Soon after this she describes a racially charged instance between two people in a car, a moment which ‘you drive straight through…acting like this moment isn’t inhabitable, hasn’t happened before, and the before isn’t part of the now’ (10). In these instances, Rankine is interested in exploring a form a racism very different to the sexual violence enacted upon black female bodies; rather, she speaks to ‘ordinary’ or ‘intimate moments’ of day-to-day life where racism raises its head in surprise (Mormorunni 6). Rankine exposes this form of ‘casual’ or ‘acceptable’ racism as having sprouted from a deep and longstanding history of racism, rooted in slavery. As the reader works their way through, and is pulled into, these intimate and ordinary moments they become increasingly aware of the fact that the ‘before’ is still very much a part of the ‘now’; that ‘the body has memory’ (28), in fact there is an ‘historical self’ (14), and that the past cannot be put behind you as it is ‘buried in you’ (63).

Rankine is able to quite literally pull the reader into these scenarios through her ‘disorienting pronoun play’ (Mormorunni 10) where she conflates the ‘you’ and ‘I’ of the story, making her own experience ours (11). Who the ‘you’, ‘I’, ‘he’, ‘she’, or ‘they’ refers to is never quite clear, making the reader do the work to decode the scenario and further implicate the reader in their involvement in the unfolding moment. However, the pronoun play does more than pull the reader into the racist scenario: these fractured pronouns point towards a fractured sense of identity for the black individual living against ‘a sharp white background’ (Rankine 52-3). A number of times throughout the book Rankine refers to this feeling of ‘displacement’ (153), the ‘feeling [that] you don’t belong so much to you’ (146).

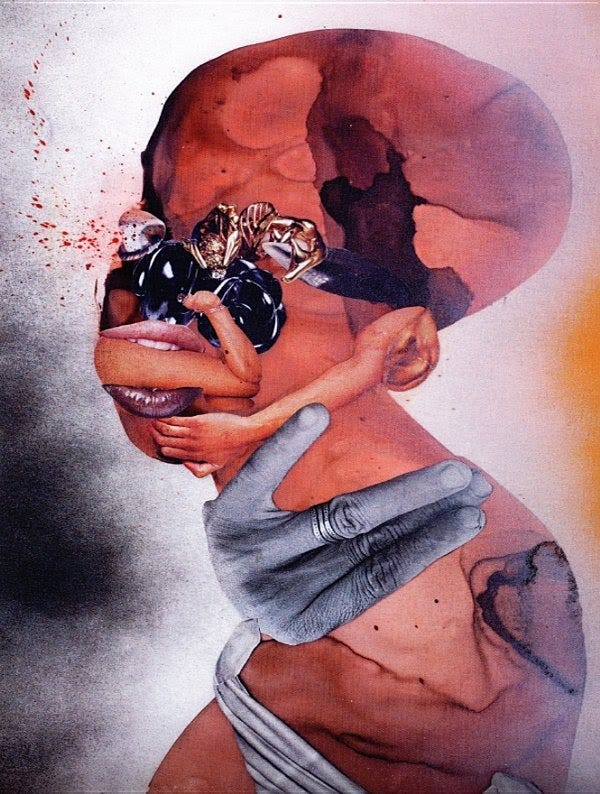

I find that this concept is best explored through the art Rankine choose to include in the book, namely Kate Clark’s Little Girl (19) and Wangechi Mutu’s Sleeping Heads (147). Rankine states that these pieces were important to her work as they ‘performed, enacted, and depicted something ancient that I couldn’t or didn’t want to do in language’ (qtd. in Clark, kateclark.com). Both pieces bring together that which doesn’t belong together, they are ‘wrong’ and appear disturbing to a certain level. Clark’s Little Girl sculpture, which depicts a black girl’s face attached to a taxidermized infant caribou, is particularly interesting to me as it speaks to a number of themes explored throughout the lyric.

The uncanny or ‘Unheimlich’ nature of the sculpture mirrors the narrator’s feeling of displacement from oneself, whilst also evoking the sense that one is hunted, weak, and defenceless. Most importantly, however, for Rankine it reminds her that her ‘historical body on this continent began as property no different from an animal’. She goes on to say; ‘So when someone says, “I didn’t know black women could get cancer,” which was said of me, I see that I am not being seen as human’ (qtd. in Clark). Ultimately, for Rankine the casual and acceptable racist ‘slippages’ that she encounters in ordinary day-to-day life cannot be detached from the longstanding history of racism that is rooted in slavery. Little Girl speaks to both the present, seemingly ‘ok’ racism that sees her as something slightly different to human, and to the brutal history of slavery, the violent treatment of black people as literal objects and animals, of which the latter stems from. (Left: Little Girl, Kate Clark 2008)

Using an array of written and visual art forms, Citizen is able to express the belief that racism is not only ever present in society but is, in its ‘lesser’ and more acceptable forms, still rooted in the legacies left from slavery. For many like Rankine, to believe in a ‘post-racial America’ is to ignore this legacy and history, as if it does not still impact the lives of those who live in a society formed from it. The usurpation of the #MeToo movement by the white affluent voice provides a contemporary example of how an inherently racial issue can be stripped of its history and thus displace the victims of that history. Rankine poignantly ends her book with The Slave Ship, pointing towards the truth that all forms of contemporary racism starts and ends with the legacy of slavery.

Bibliography

- Clark, Kate. ‘Cultural Collaborations’. USA: kateclark.com, 2022. (Online resource, https://www.kateclark.com/cultural-collaborations).

- Clark, Kate. Little Girl. 2008.

- Ram, Christelle. ‘Black Historical Erasure: A Critical Comparative Analysis in Rosewood and Ocoee Rosewood and Ocoee’. Honours Programme Thesis. USA: Rollins College, 2020. (Online resource, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors/121).

- Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. UK: Penguin Random House UK, 2014.

- Riley, Rochelle. ‘#MeToo founder Tarana Burke blasts the movement for ignoring poor women.’ USA Today News, 16 November 2018. (Online resource, https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/11/16/tarana-burke-metoo-movement/2023593002/).

- Mormorunni, Cristina. ‘The Trauma of Racism in Translation: Making the Personal Universal through Language, Point of View and a Raced Aesthetic’. USA: TerraMar, 2017. (Online resource, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://terramarconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Trauma-in-Translation.pdf)

- Mutu, Wangechi. Sleeping Heads. 2006.

- Turner, Joseph Mallord William. The Slave Ship. circa 1840.

The connection drawn between the MeToo movement, its “affluent white voice” and the lived black experience and history of abuse and violence is something that is really interesting in this post. What I found particularly striking here was your section on the use of specific pronouns in Claudia Rankine’s text, how “she conflates the ‘you’ and ‘I’ of the story, making her own experiences ours (11)”. It led me to consider how the white voice is always made louder than the black voice and how in this instance, giving the pronoun ‘you’ to her reader, Rankine cleverly places readers inside the story. Sometimes the reader may be white, which creates and mirrors the tension that exists in the real world where the white experience stands on the shoulders of the black experience, like the MeToo movement and how white Hollywood actors were able to make it their own despite its actual origins. I think the way that readers are drawn in through the conflation of pronouns is engaging on both a creative level and in a way that encourages certain audiences to reflect on the experience they are placed in, how it relates to their own experience, and how difference of race can be highlighted depending on the race of the reader. The irony of putting a white person in the story of a black person links interestingly to the real-life situations where white people consistently take the spotlight away from black bodies and mark it as their own.

Thanks for your comment Eimear! I’m really glad you found my blog post interesting and clear. I really like how you describe the white voice being louder than the black and, particularly, how ‘the white experience stands on the shoulders of the black experience’; this was exactly what I was trying to explore by bringing the MeToo movement into the discussion. Your final comment that Rankine’s pronoun play ‘take[s] the spotlight away from black bodies’ sums it up well, as it is the physical black body that Rankine draws attention to time and time again throughout the book.

Emily, I found your post incredibly well researched and detailed! Your point regarding the uncanny nature of the sculpture, and its alignment with the historical notion of property was particularly interesting. Ideas of memory come to the fore; the past is evoked, though not directly, rather through feeling and bodily experience. As you suggest, Rankine’s inclusion of Little Girl works in-tandem with her exploration of microaggressions – it reflects the experience of being ‘othered’. Later in the text, Rankine writes “What else to liken yourself to but an animal, the ruminant kind?” (60). Rankine’s reference to the “ruminant kind” parallels her inclusion of Little Girl; a “ruminant” animal refers to a grazing mammal, in turn harking towards notions of inescapability (60). Rankine hints at the inescapability of racial injustices and incidents, whilst dually harking towards a demand for change and justice, as reflected in the last line of Citizen (2014), “It was a lesson” (159).

Your discussion on the true origins of the “Me Too” movement was very insightful. I think you’re completely right that although it does encourage solidarity, it encourages it among a select group of people. In this way, it erases and marginalises the experience of so many other people. Your analysis on the images was also very enlightening particularly the fact that the inclusion of the painting “The Slave Ship” dispels the notion that we are living in a “post-race society”. I think this is Rankine’s purpose in writing this text is to show that the prejudices and marginalisation that existed in America’s past are just as prevalent now.

I found it really interesting how you contextually have drawn the novel back even further into recent history with the #MeToo movement – I wasn’t aware of the extended history of the movement, so I found it very insightful. I also like how you’ve drawn this into the overarching narrative of Citizen, and made it incredibly relevant regarding the erasure of black identity and actions. My question is can these movements co-exist? If the presence of the 2017 #MeToo overshadows the historical movement by black people, surely the suggestion is not? But also, the modern MeToo movement has made great strides in assisting people too. It’s a complex question I’m torn about. On a separate note, I really love the use of the word “uncanny” – reading Citizen always felt strange because there is a sense of strangeness throughout the text, and perhaps uncanny is the only way to describe it. Drawing it back to visual art forms is also a very interesting comparison to make too – it helps amplify the novel’s strange and abstract tone at times.

Hi Emily! I really enjoyed reading your blog, and your discussion about the origins of the #MeToo movement was really interesting and perceptive. The long and well-documented history of white celebrities co-opting and appropriating the work of activists of colour makes solidarity only seem possible with the most privileged and loudest group. The affluent white voice ringing louder than the voices of people of colour is evident in Rankine’s writing. Your focus on the use of pronouns was very clever and insightful. The protagonist ‘you’ and her sense of invisibility as a woman of colour, when white people fail to properly acknowledge her, draws many similarities to Burke being lost among white celebrities.

I loved your blog Emily! I particularly loved your links to the different art forms that are used throughout the lyric. I love how you picked up on how Rankine ends her book with The Slave Ship, and the point you raise that this is still the truth and that all forms of contemporary racism starts and ends with the legacy of slavery. The point on the ‘othering’ of blackness and the ‘Unheimlich’ was fascinating, and raises questions on narrator’s feeling of displacement from oneself.