Laoise McWilliams

‘Who am I? And how can I be that person?’

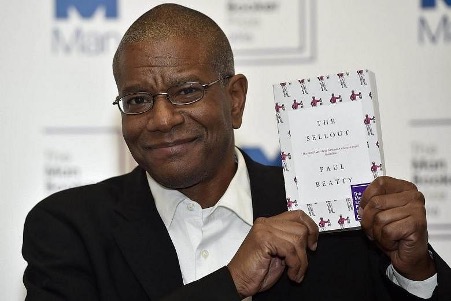

These two questions form a central motif in Beatty’s 2015 The Sellout sustaining an interrogation into identity throughout the novel. The narrator, Me or Bonbon, is introduced to the soothing nature of the questions by his father a psychologist sent to get a ‘psychotic motherfucker to lower his gun.’ His Father’s voice had ‘a way of relaxing the enraged and allowing them to confront their fears anxiety free.’ Beatty similarly employs a soothing authoritative voice to delve into key issues facing Black Americans in a ‘post-race’ society through his use of humour. By embedding humour into the fabric of the novel Beatty offers a dynamic narrative reflective of multifaceted nature of humans and emphasising societies unwillingness to substantively address race issues. In the prologue of the novel Bonbon on trial in the Supreme court states:

‘Your honour, I plead human.’

His objection to the binary negotiations of guilt instantly shatters ideas of typical human nature. He is neither guilty nor innocent with the simplistic and honest style of language imbuing the scene with a theatricality and humour. Naughton argues that by pleading human Beatty questions ‘the universalist ideal of an ordinary and irreducible humanity underlying and legitimising legal definitions of phrases like “human rights” or “crimes against humanity”.’ What we mean by human and an overarching sense of identity is presented as futile and exclusionary as the terms do not reflect Bonbon’s reality. Furthermore, the typical trappings of identity are stripped of Bonbon as he explains:

‘Like the entire town of Dickens, I was my father’s child, a product of my environment and nothing more. Dickens was me. And I was my father. Problem is they both disappeared from my life, first my dad, and then my hometown, and suddenly I had no idea who I was, and no clue how to become myself.’

The consumptive and encompassing language propels the notion that the grounding features of identity, place and family, are denied Bonbon and the population of Dickens. Markers of home and safety are usurped continually leaving the inhabitants in a state of identity crisis. Who they are is lost and progression doesn’t exist within typical linguistic terms. Beatty has created a framework to allegorise the experience of Black people as ‘notions of human identity itself as universal or unchanging may be recognised as a historical construct constituted by the exclusion, marginalisation and oppression of racial others.’ (Bennet & Royle) If Black identity is not included in universal ideals Beatty is pinpointing the failure of language and the repercussions of a loss of identification and belonging.

As a response to being ‘exiled to the netherworld of invisible L.A communities,’ Bonbon draws a border around the town. Through his diagram on his ‘empowerpoint’ he writes binaries such as:

‘WHITE AMERICA / DICKENS,’ ‘THE HOOD / NO MATTER HOW MANY TIMES REFERRED TO AS THE HOOD – NOT THE HOOD,’ and ‘THE BEST OF TIMES / THE WORST OF TIMES.’

Beatty is pinpointing the essential differences between the black community and the surrounding neighbourhood and deliberately portraying black life as a place in opposition to those around it tapping into stereotypes and tropes created by a white-centric narrative. However, he does so through humour and with a creative playful tactic. Beatty himself asserts that ‘Humour is vengeance’ to satirise or mock the harsh reality is presented as an affective form of rebellion. The essential humour does not distil the seriousness of the content as even Bonbon reflects ‘I was more serious about this than I thought’ and felt that the border invoked an ‘implication of solidarity and community’ even though ‘it was just a line.’ The border offers a space of control and importance, it invokes a sense of belonging which whilst humorous it re-establishes a sense of community. Similar to the relaxing tone Bonbon’s father used to ‘make the client feel important, to feel that he or she is in control of the healing process.’ Bonbon’s border is a psychological tool to help rebuild identity compounded by humour that exemplifies the rage and sense of loss experienced by Bonbon.

At the end of the novel Bonbon reflect that ‘Silence can be either protest or consent, but most of the time it’s fear.’ Whilst throughout the novel Bonbon focuses primarily on external markers of identity such as mottos, borders, and signage he distils fear through the use of humour. The novel concludes with Bonbon explaining:

‘I’ve whispered ‘Racism’ in a post-racial world.’

And in doing so ironically ‘managed to racially discriminate against every race in the world all at the same time.’ The act of whispering correlates with soothing, he exposes the fragility of societal structures and the ideological delicacy of America and the fault lines hindering identity and belonging. In doing so Beatty fulfils Frank Wilderson III’s request for ‘something that celebrates the absoluteness of rage’ yet this rage is presented through calming terms and humour. Beatty reflects on the rage and loss by using his humour as a form of vengeance he writes ‘if an increasingly pluralistic America ever decides to commission a new moto, I’m open for business.’

Bibliography:

Aaron Robertson, The Year Afropessimism Hit the Streets?:A Conversation at the Edge of the World, 27 August 2020

Beatty, Paul. 2016. ‘The Sellout.’ (Germany: Oneworld Publications)

Beatty, Paul. 2008. Hokum: An Anthology of African-American Humor. (United States, Bloomsbury Publishing)

Bennet, Andrew & Royle, Nicholas. 2016. ‘An Introduction To Literature, Criticism and Theory’ (Oxon: Routledge

Gerald David Naughton. 2023 “‘Pleading Human’ in Paul Beatty’s The Sellout”, Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 64:3, 443-452, DOI: 10.1080/00111619.2022.2047879

This blog post touched on a number of topics within Beatty’s novel and was wide-ranging in its scope. At the beginning of your post I found it interesting how you compared the father’s soothing voice to the ‘soothing, authoritative voice’ of Beatty. As you have demonstrated, I find that it is Beatty’s humour that allows his voice to be described as ‘soothing’, due to its unabashed boldness. The novel is littered with examples of this bold humour, not least of all in the opening pages. In the Prologue alone Beatty facetiously addresses racial stereotypes (‘This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything’, 1); racist tropes (‘“Some of my best friends are monkeys,” she said accidentally, 5); and, the n-word, accompanied with the harsh ‘-er’ ending (12). Beatty immediately makes the reader aware of his reluctance to shy away from these issues and, perhaps in a far-reaching and abstract way, reminds me of Bonbon’s experience of guilt. Sitting in the Supreme Court, Bonbon waits for ‘that familiar, overwhelming sense of black guilt’ (17) but instead finds relief in being a black person who has ‘actually done something wrong, because that relieves [him] of the cognitive dissonance of being black and innocent’ (18). The way in which Bonbon’s crime relieves and ‘soothes’ him, for the worst, seemingly inevitable thing has happened to him, reminds me of how the reader is relieved and ‘soothed’ by Beatty’s blunt humour: in a book about contemporary Black America the racist stereotypes, tropes and slurs are addressed immediately, in a humorous way. The reader, perhaps particularly the highly self-conscious white reader, is at first gobsmacked by the boldness of Beatty’s humour but then settles into the relief of not having to ignore or tiptoe around the topic of race. It is as if Beatty soothes his readers by theoretically addressing the elephant in the room. Like Bonbon’s criminality and guilt, the worst has happened; the racist jokes and words have been said. As you concisely demonstrated and quoted, Bonbon and Beatty have ‘whispered ‘Racism’ in a post-racial world’. The post ends, having come full circle, with a great point about the act of whispering correlating to both the act of ‘soothing’ as well as the ‘fragility’ and ‘delicacy’ of American societal structures. Your post raises much more to discuss surrounding the issue of identity, however I have no more words left!

Paul Beatty’s use of humour throughout ‘The Sellout’ is rather ambiguous when it comes to analysis, and one is often left wondering if it is appropriate to laugh at the comical moments (heightened by the text’s tense concluding comedy club scene). However, this is precisely where your blog becomes incredibly beneficial. You provide a reading of Beatty’s humour early into your piece, becoming particularly interesting when you associate said humour with one’s psychological process. While it is an uncomfortable point to discuss, I thoroughly agree that Western society’s inability to beneficially discuss the contemporary African American condition shines through in the text. Your point on Bonbon’s entrapment (both in terms of his society and identity) leads to much further analysis, and the correlation between Beatty’s more contemporaneous novel and Whitehead’s heavily historically-based piece comes through here, Bonbon in a sense sharing in Cora’s environmental desensitisation, however in a vastly different context. This continues into your further analysis of black displacement, which shows once again that, despite the abolition of slavery almost two centuries ago, not much has changed for the African American community in terms of their lack of identity, as you make clear through your reference to Bennet and Royle. To revert to humour, however, I found Beatty’s own description of humour as vengeance, highlighted in your blog, to be highly beneficial to my understanding of the intention of humour in the text. I support the idea that humour doesn’t take away from the true, antiracist messages throughout the text, and actually find humour to be a highly effective ploy by Beatty in keeping the reader engaged and thus aware of contemporary Western issues around racism. This is a very academically prompting piece!

Great blog-post on the humour of rage – as a means of exploring the absurdity of claims about the US as a ‘post-racial’ society. As you show us, Beatty explores with wincing precision the realities of segregation which in Dickens at least have never gone away. I also really liked your use of Wilderson’s remark – ‘something that celebrates the absoluteness of rage’ – and I wondered here whether there was scope to think about Wilderson’s work on Afropessimism and your claims about the human and humanity in Beatty’s novel. For if Wilderson argues that the human is a category that is denied to Black subjects (‘Blacks do not function as political subjects’ ) because the human is category is defined by or through its negation or repudiation of blackness, then how might we think about what Beatty is seeking to do in the novel? One answer is that The Sellout constitutes some kind of retort to the bleakness or pessimism of Wilderson’s claims and that humour in the novel is tied to an effort to reclaim or rework some notion of the human without falling into the trap of a liberal-humanist universalism.

In a novel wherein humour can be at times ambiguous, and a challenge to circumnavigate, your blog post has helped provide some great insight into Beatty’s co-option and subversion of humour – and this point in particular rings true of this sentiment:

“By embedding humour into the fabric of the novel Beatty offers a dynamic narrative reflective of multifaceted nature of humans and emphasising societies unwillingness to substantively address race issues”.

Continuing to draw on comedy, the comedy club scene acts as an allegory for the novel. Within the scene, a black comedian makes a joke, and a largely white audience laughs – he states, “this shit ain’t for you” (287). Some may espouse the sentiment; individuals may read The Sellout, and feel similarly, and as such, suggest that the book must be safeguarded against a certain kind of readership. Yet, Beatty does better, and upends this sentiment, by having BonBon consider who the comedy is for. Throughout the text, Betty raises admirable questions alike ‘who is the comedy for?’, yet he eviscerates any chance of finding an answer, and instead opts for an ambivalence to everything surrounding the ‘self’.

I found your analysis of the objection to the binary confines of law very interesting. The terms “guilty” or “non-guilty” do not reflect BonBon’s experience so instead he “pleads human”.Wilderson states in his book AfroPessimism and Its Discontents that the world’s binary frame for anti-Blackness isn’t white people versus black people but humans versus slaves. In this case, slave means any black person and human as any privilege white person. By pleading human, BonBon removes himself from the binary terms that serve to restrict him.

I really enjoyed the discussion around borders. I recently read Shinkel’s work “State Work and the Testing Contours of Citizenship”. This work discusses how borders simultaneously demonstrate yet weaken power. It shows that the area has a limit of power but within that space, that area is theirs; it enacts a sense of ownership. I think this is BonBon’s motivator as all his life events have happened around him and to him as a result of being in a white-centric narrative but he has felt on the periphery. Through creating boundaries, he can get Dicken’s on the map which gives him a sense of ownership in a life that he has never had much control over.