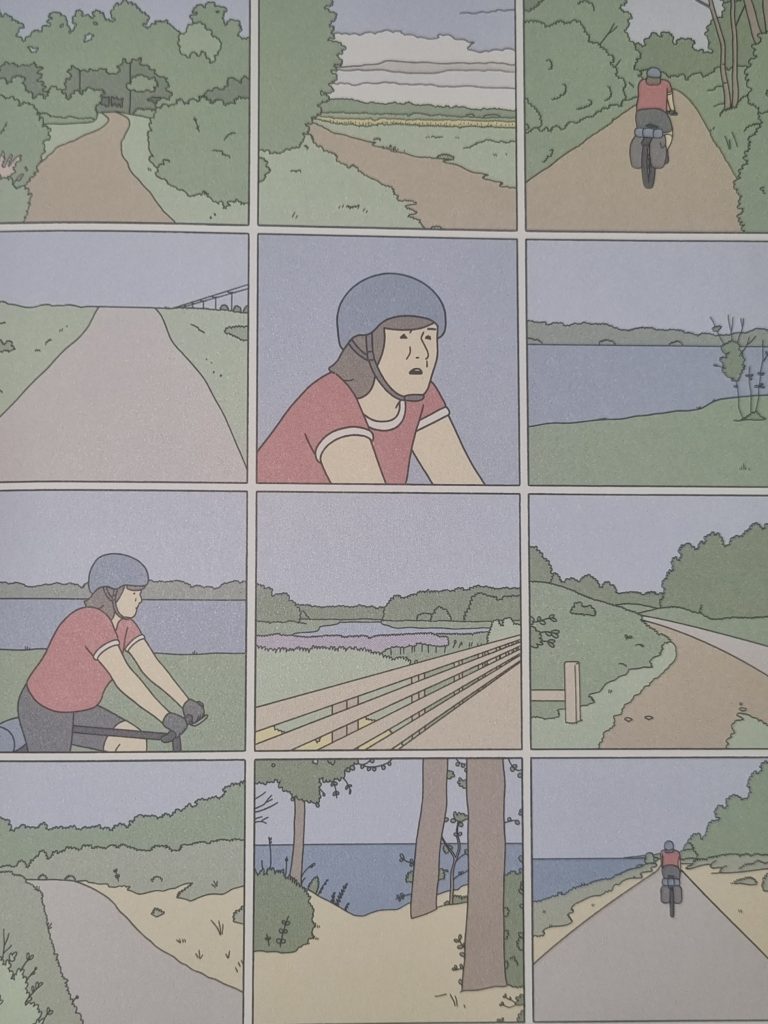

Throughout Ling Ma’s novel Severance, the protagonist Candace experiences the demise of all her relationships, such as the loss of her parents, the end of her romantic relationship with her boyfriend, and her eventual departure from the other survivors during the End. While Candace demonstrates a reluctance to let go of some of these relationships, exemplified through the maintenance of her boyfriend’s retainer in the mouthwash solution after their breakup, or through her communication with her deceased mother throughout the novel, the relationship she finds most difficult to sever is the one she has with capitalist society.

This is constant throughout the novel, and even by the end of the text Candace is in a clear state of denial about the downfall of modern society; she fantasizes about the purpose of the city and a participation in its ‘impossible systems’, which breed work and routine. In the end, Candace, unable to accept a new way of life, makes her way towards the city in search of emotional fulfilment as well as survival.

“To live in a city is to consume its offerings. To eat at its restaurants. To drink at its bars. To shop at its stores. To pay its sales taxes. To give a dollar to its homeless.” (page 290).

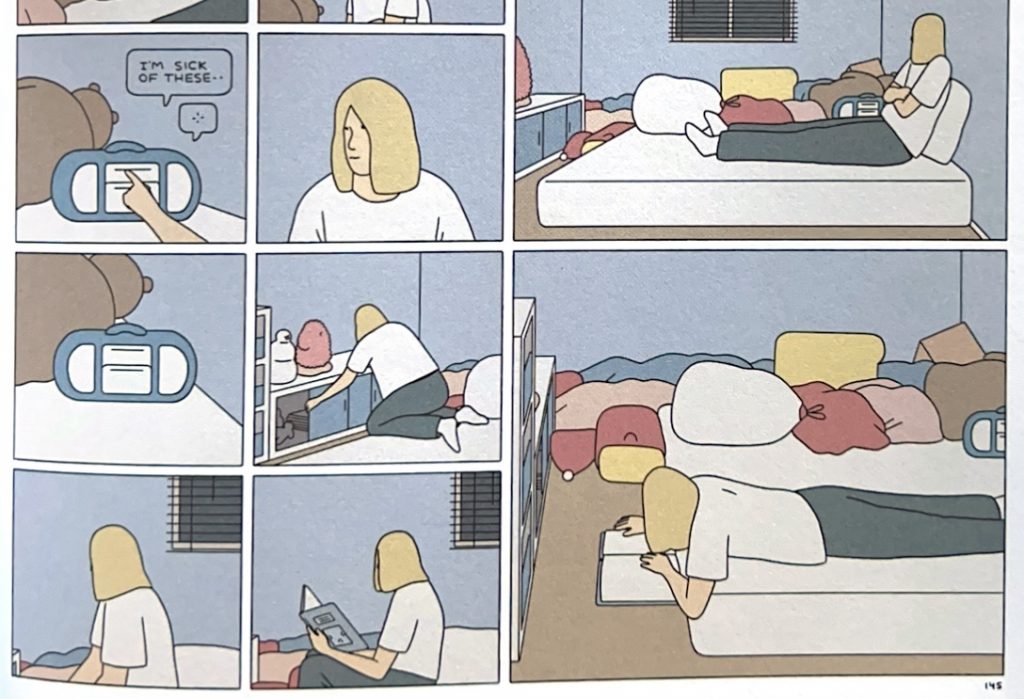

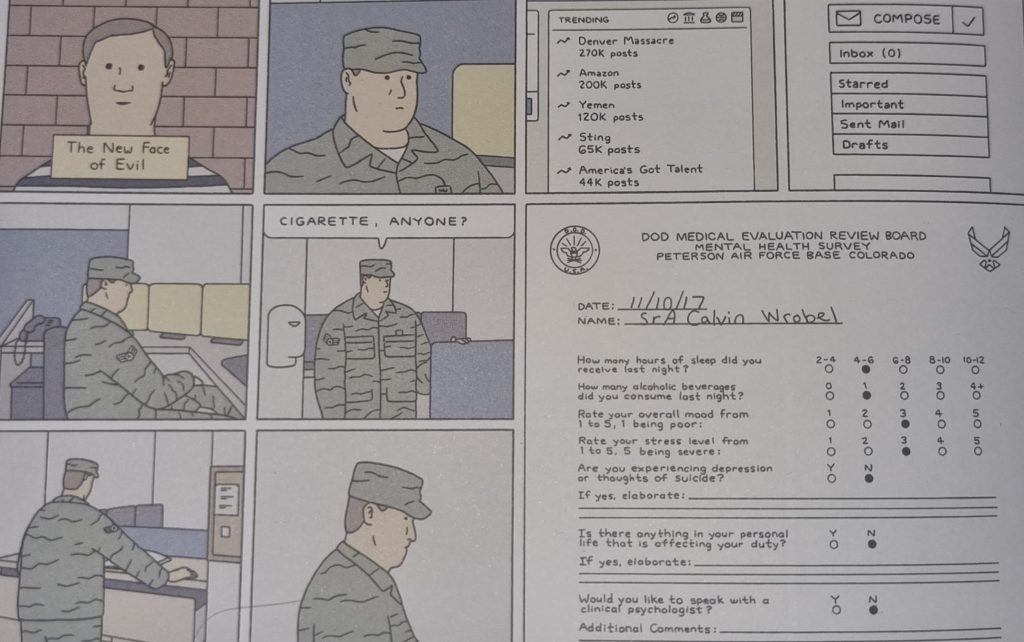

Candace’s reluctance to let go of her capitalist mindset is justified partly in the novel by Ma’s portrayal of waste culture and the overproduction which takes place under capitalism. Unlike typical apocalyptic narratives, there is no scarcity of resources for Candace and the other survivors, who have access throughout the text to bottled water, beer, drugs, and packaged foods.

“There were so many candy options: marbled jaw-breakers, Bananaramas, Skittles, M&Ms, Wicked Watermelons, Hot Chews, Hot Tamalees, Reese’s Pieces, Good & Plentys” (165).

Is it any wonder Candance maintains her loyalty to capitalism when her surroundings remain crudely emblematic of her previous life?

Ma also satirises this surplus through Candace’s offerings of luxury goods to her parents through the spiritual realm, who she imagines combing through the abundance.

“I imagined that it would be more than they would ever need, more than they knew what to do with, even in eternity”. (106).

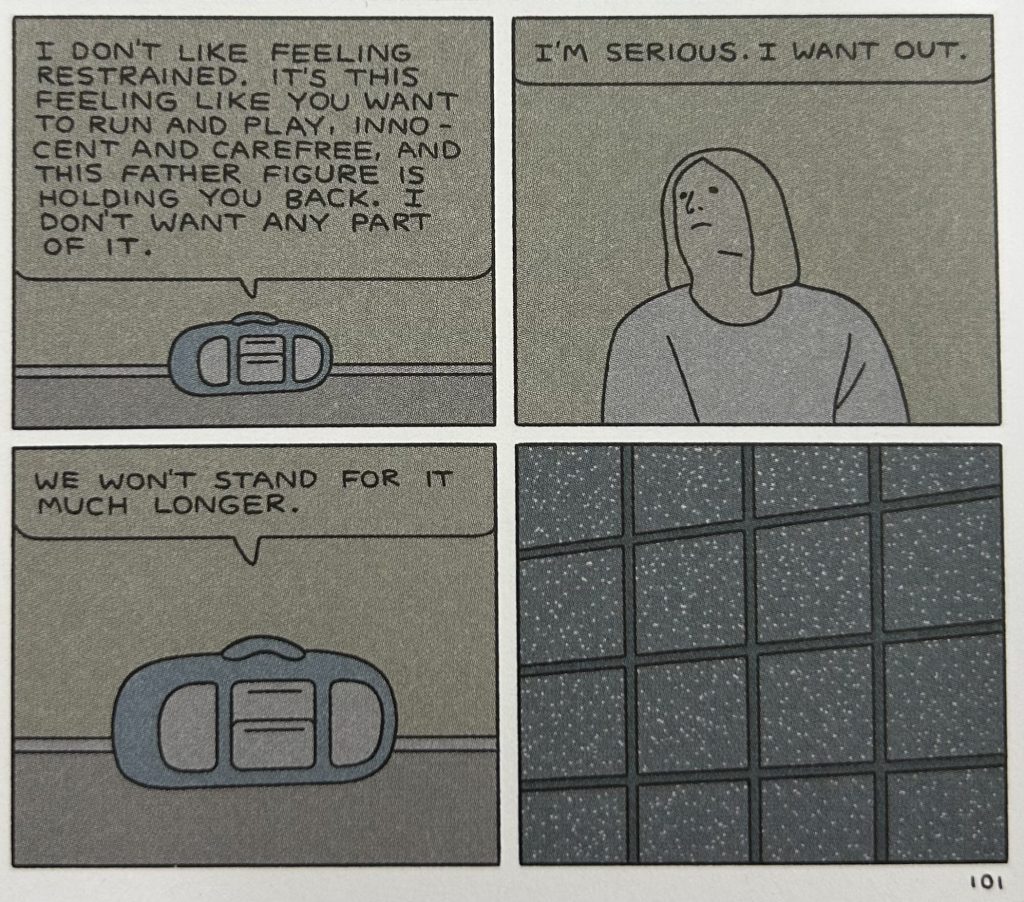

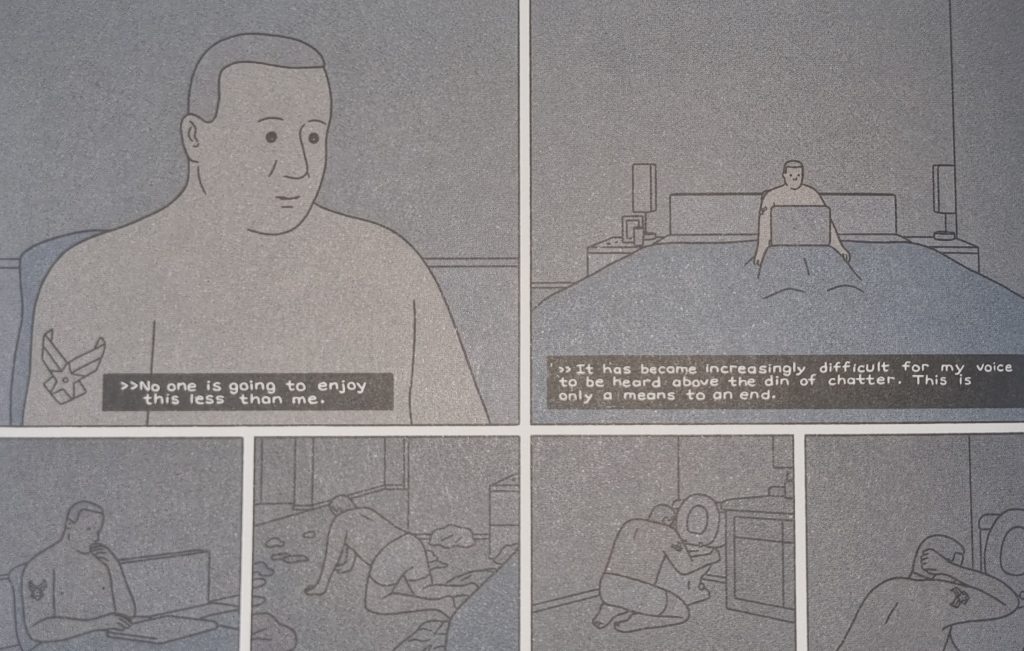

Throughout the novel it also becomes increasingly harder to distinguish Candace from the fevered as her routines become monotonous and pointless. Even after it becomes clear Spectra is no longer functioning as a corporation, with the office deserted and unable to produce goods, Candance changes out of her commuting trainers into a pair of office flats before starting her shift. She also admittedly functions on instinct when opting for a receipt after drawing out her final pay check, despite the fact it is now clear even to Candace herself that her working life in New York has come to an end. These habits mimic those of the fevered and in this way the fevered serve as an extended metaphor throughout the novel for enslavement to modern day capitalism. This is most obviously conveyed in Candace’s imprisonment in the L’occitane store at the Facility -a physical embodiment of the mental binds she refuses to shed.

“I was a creature of habit, as it turned out.” (262)

The Culture Industry

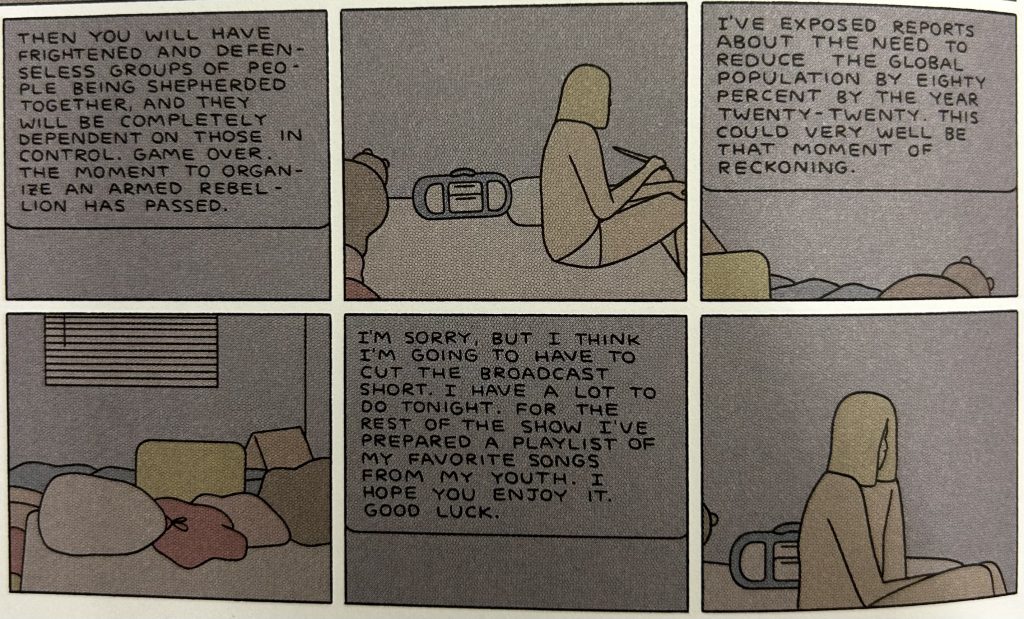

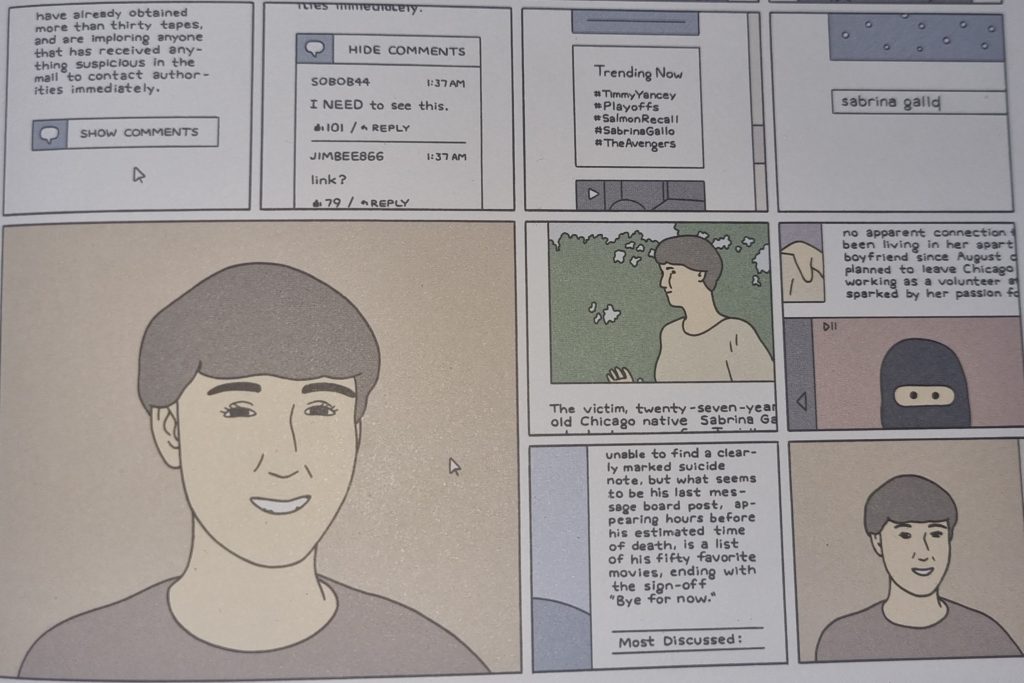

Candace’s reluctance to rid herself of a capitalist mindset can be explained by drawing parallels between Ma’s Severance and Adorno and Horkenheimer’s theory of Culture Industry in the Dialectic of Enlightenment. This is the theory that popular culture works similarly to a factory in producing goods, which are used to manipulate and create a society of mass passivity. The Culture Industry, according to Adorno and Horkenheimer, provides standardized mass goods for every member of society under the guise of individualism, so that it’s impossible to escape the industry –“something is provided for everyone so that no one can escape”(Adorno and Horkenheimer, 97). Even in entertainment, which is described as “the prolongation of work under late capitalism,” there remains constant advertisement so that leisure can never be achieved (Adorno and Horkenheimer, 109).

The Culture Industry pervades the novel and is displayed proficiently by Ma through the acts of Lane’s fevered neighbour, who flicks through television channels mindlessly and without critical thought.

“T-Mobile was offering a new no-strings attached carrier plan. She laughed. Neutrogena Blackhead Eliminating Cleanser, blasting blackheads all over your face. She laughed. The new Lincoln Centre Town Car. French’s Mustard. The latest Macbook. She laughed.” (156).

In Severance, Candace’s desperation to cling to her familiar capitalist life, and the loss of relationship with those around her is demonstrative of the detrimental effects of the Culture Industry -on human connection, on survival instincts, and on individual thought.

“Leisure, the problem with the modern

condition was the dearth of leisure”. (199).

References

Primary text

Ma, Ling. Severance. Text Publishing. 2018.

Secondary resources

Cambridge Dictionary | English Dictionary, Translations Thesaurus.” Severance, dictionary.cambridge.org/. Accessed 20 Nov. 2023. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/severance#google_vignette

Adorno, Theodor and Max Horkenheimer. “Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Dialectic of Enlightenment , Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1947, pp. 97–109.