By Fleur Howe

“With all due respect, you don’t look like you’ve been babysitting tonight.”

Appearance and dress underpin Emira’s social power, and lack thereof, in Kiley Reid’s novel Such a Fun Age (2019). Accused of kidnapping the child she babysits, Emira is told she does not ‘look’ like a babysitter. Calling to question what a babysitter is supposed to look like – or rather how a woman of colour is expected to present herself. It is undeniable that Emira was accused not just because she was with a white child at night, but because she was not dressed in ‘uniform’. This incident signifies a not so micro, microaggression that results in ‘constant reminders that you don’t belong, that you are less than, that you are not worthy of the same respect that white people are afforded’ (Oluo, 165).

“She wouldn’t have gotten in trouble that night if she’d been wearing uniform.”

(Reid, 228)

Uniform not only represents the black woman’s necessity to be presentable, but also represents the not so invisible traces of slave relations. Alix dresses Emira in a uniform with the family name on it to instate a sense of ownership over her child’s babysitter. ‘At least I’m not still requiring a uniform for someone who works for me so I can pretend like I own them’(Reid, 227), Emira is branded with her employers name in a display that labels her as acceptable or safe to the kind of privileged white people that harassed her when she was not in uniform. For the ‘shabby black person might be read as dishevelled, wild and threatening’ (Dabri 2019, 26). Out of uniform, in her own clothes Emira is threatening because she is not visibly white or white-adjacent to her employer.

Equally, Emira’s uniform signifying her as property underpins the class and wealth disparity between her and her white employers, a disparity which ‘reveal[s] the effects of accumulated inequality and discrimination, as well as differences in power and opportunity, that can be traced back to the inception of the United States’ (Dabri 2021, 122). Alix is ironically aware, and embarrassed of presenting her privilege in front of Emira ‘she took the tags off clothes and other items immediately’, ‘Alix no longer felt comfortable leaving out certain books or magazines’ (Reid, 138). She hides her spending habits as if hiring Emira is not in itself a signifier of her privilege. Their relationship portrays this engrained power imbalance and is emblematic of slavery in the United States, Alix’s childhood home even being described as having ‘plantation columns standing out front’ (Reid, 108). Alix effectively owns Emira, her poor attempt at closing the class barrier between them by hiding her expenses only signifies Alix’s lack of accountability, not her allyship or sympathy towards her black employee.

Emira is plagued by the necessity for the black woman to be constantly presentable. Tamra, Alix’s friend is condescending towards Emira about her braids ‘I’m guessing you’re afraid to go natural’ (Reid, 164) While Tamra is, from her perspective, supporting Emira’s right to wear her hair in its natural state; Tamra is simultaneously highlighting her ignorance and privilege by insinuating Emira’s fear of wearing her natural is purely cosmetic. Emira is not granted the privilege to appear anything but acceptable in the eyes of a white person, the conflict in the supermarket asserts this as fact.

Whilst being shabby makes Emira a threat, Alix pretends to be less wealthy ‘pretending – in front of Emira – that she was about to eat leftovers’, highlighting how ‘the carefree insouciance of shabbiness does not invoke the same social costs for a white person: their lack of effort will be afforded a value perhaps elevated to chic’(Dabri 2019, 26). Alix’s pretence is an attempt to lower herself to be closer to Emira’s social standing, but in doing, so she affirms that she views Emira as lesser.

Emira’s boyfriend Kelley is has an ignorant understanding of racial discrimination, his limited perspective leads him to think about race only when he witnesses discrimination. Emira asks him to ‘remember we have different experiences’ (Reid, 194) his outrage at her uniform highlights this. His comment ‘You should get to wear your own clothes with people who deserve you’(Reid, 190) is ignorant to how when she wears her own clothes she is subjected to oppression and harassment. Emira’s uniform represents the inescapable necessity to present herself in a certain way, a way a white man cannot understand. ‘The white body is not subject to the same regulatory procedures as the body racialised as black’ (Dabri 2019, 26) Kelley goes to work in a ‘t-shirt’, and ‘will never have to even consider working somewhere that requires a uniform’ (Reid, 191) Not only does Kelley not have to work a lower wage job like Emira, but he does also not have to uphold a certain presentability to be respected. Even for Emira’s birthday she is gifted ‘interview shirts’ (Reid, 234) from her friend, indicating that no matter the job, no matter her position she will still have to uphold a certain white-pleasing appearance.

The conflict that underpinning the entire novel is the representation of the conjunction between microaggressions and appearance. The relationship between presentability and the perception of black people as inherently threatening and unprofessional. Dabri argues that ‘until white people are prepared to see us as ‘innocent’ … racism is present’ (2021, 121), asserting that no matter what Emira does, she is not innocent in the eyes of a white person. Emira therefore highlights that to be safe, and be considered safe, she must present herself as white normative, or owned by a white person.

Works Cited:

Primary:

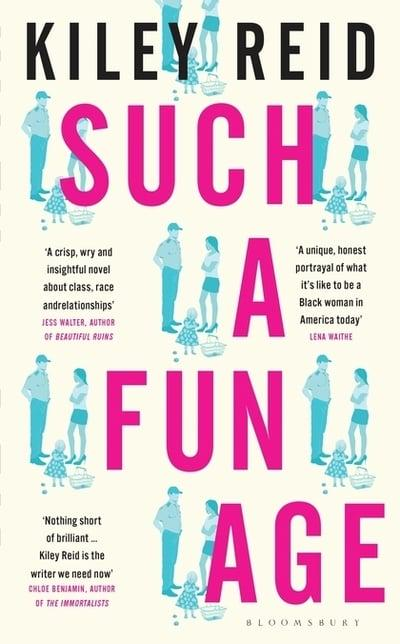

Kiley Reid, Such a Fun Age. Bloomsbury, 2019. Print

Secondary:

Dabiri, Emma. Don’t Touch My Hair. Penguin Books, 2019. Print

Dabiri, Emma. What White People Can Do next: From Allyship to Coalition. Penguin Books, 2021. Print

Oluo, Ijeoma. So You Want to Talk about Race. BASIC Books, 2020. Print

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/31/books/review/such-a-fun-age-kiley-reid.html

You’ve given us a lot to think about in terms of the complex links between roles, stereotypes and race – and how the visibility and indeed performativity of race marks sameness and difference. The fact that Emira is not dressed as a nanny or servant and is misrecognised by the white security guard marks the first of many mis-recognitions or, as you say, microaggressions that Reid explores to such devastating effect. The fact that Alix and indeed Kelley are unaware of the ways they mis-recognise or mis-represent Emira is of course the point, as you detailed so well. But I wonder if there might be scope to think about how Reid examines Emira’s responses to these moves to frame her in a set of limiting roles or subject-positions? What do her refusals and her awkwardness (and silence) in the face of power tell us? Here Yao’s work in Disaffected – and her moves to identify counter-strategies to she calls the ‘liberal politics of recognition’ – might be of interest. Emira’s resistance is careful and even subdued but her refusal to succumb to the limits Alix and Kelley seek to impose does seem to be worthy of further investigation.

Thank you for your comment, I think the question you pose regarding Emira’s silence is really interesting. I believe her silence and awkwardness are used to represent the silencing of black voices in a white space. The novel itself perpetuates this standard by focusing so heavily on the voices on Alix and Kelley.

Your blog post made me reconsider the ways in which representation and appearance tie in with race. You highlight the different interactions that are supposedly only about representability, and yet they are actually about race and class. The examples you provide made me think about the performativity of race; how Alix hides a corporate agenda behind her own ‘activism’, how Emira is supposed to dress while she’s working, how she should wear her hair, how she should appear on TV, how she cannot be a babysitter because she wearing a short dress and heels, and how Alix pretends to eat leftovers to bridge the distance between Emira and Alix’s backgrounds. It becomes abundantly clear that race is not just a matter of skin colour, it’s about performing different roles that are accepted in predominantly white spaces. I was also very interested in comments on the themes of innocence and ownership in this novel. Alix and Kelley were absolutely insufferable at times, and sometimes I wished that their voices would be silenced, but their perspectives did provide an insight into the uncomfortable truths that are linked to race, innocence and ownership, and in that way they were important to the narrative.

I really enjoyed reading your interesting post on uniform in Such A Fun Age. Something I found particularly compelling in your post was that the polo shirt Alix makes Emira wear – embroidered with her business slogan – possesses racist undertones of white ownership. Even more sinsterly, in the novel, we learn that when Alix was young, her family “purchased the services” of a “light-skinned black woman” called Mrs Claudette to work as a nanny and housekeeper in their huge house with “planation columns”. Later, Reid returns to this topic when Kelley criticises Alix: “of course you’re hiring black people to raise your children and putting your family crest on them. Just like your parents”. As you perceptively point out in your post, Reid therefore makes the invisible historical traces of slave relations, visible. While Mrs Claudette wears a uniform imprinted with a “family crest”, Emira’s shirt bears the name of Alix’s business, MeToo. In this sense we can see how the vestiges of racism persist over generations. By drawing attention to this shift from old, overt forms of racial ownership to an inisidious, corporate-friendly racism, Reid unveils a nuanced and subtle contemporary manifestation of racism, enmeshed with economic, capitalistic structures.

I find your post really interesting in terms of the idea of black people having to manipulate their own appearances in order to satiate a white population. The idea of black people having to appear as “white-adjacent” sounds bizarre but the way you have put it in context here really shows how this is a daily lived experience for black people in a seemingly “post-racial” society, which we know is just a society that is often racist in an out-right way or perpetuated by microaggressions which you touch on here. Your points about how Emira’s appearance is judged through white eyes, whether that’s Alix or Kelley through their forced efforts to come off as an ally of hers really brought to light how they value what they think is acceptable more than what Emira herself thinks. The idea that she shouldn’t have to wear a uniform speaks to Kelley’s cringeworthy forced activism which really just shows how valuable he sees his own opinion as with regards to the rights of black people. Overall I think you have done well to unveil the “not so micro, microaggression[s]” that permeate through the novel through uniform.

Hi Fleur! This is a truly fascinating blog post that made me reconsider how appearance and race factor in employment. The external behaviour of Alix’s progressiveness is shown to be a facade, the irony of hiring a black nanny to help raise her child like her parents did before her. Using the LetHer Speak polo as an unofficial babysitting uniform is a detail that uncannily mirrors the way her parents made their hired caregiver, Claudette, wear a polo with the family’s last name, Murphy, stitched across its back.