A history of racism in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (2014)

In 2017 the #MeToo movement was booming across social media, following the onslaught of allegations against film producer Harvey Weinstein. Many big-name celebrities came forth online to share their own stories and show solidarity in the face of sexual abuse, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Lawrence, and Uma Thurman to name a few. American actress Alyssa Milano encouraged the use of the hashtag in October 2017, writing that ‘If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote “Me Too” as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem’. With such big stars leading the movement we now, six years later, associate #MeToo with Hollywood.

However, the #MeToo movement was actually birthed on MySpace in 2006 by activist Tarana Burke, an African American woman who used her own history of sexual violence to support and empower other young girls in marginalised communities. Despite receiving accolades from Time magazine as a female activist and ‘silence breaker’ in 2017, Burke’s name and intention has been lost among the names and stories from (predominantly white) Hollywood stars. Only a year later, Burke claimed that ‘The No.1 thing I hear from [black, Hispanic and Native American women] is that the #MeToo movement has forgotten us.’ She added, ‘We are the movement, and so I need you to not opt out of the #MeToo movement…Stop giving your power away to white folks’ (qtd. in Riley, usatoday.com).

‘We are the movement …

(2018)

Stop giving your power away to white folks.’

Christelle Ram uses Burke and the #MeToo movement as a key example in her essay, ‘Black Historical Erasure’ (2020). Ram broadens out the affair by reminding us that ‘The #MeToo movement was partly inspired by the widespread sexual violence experienced by slave women and men’ (25). Here, Ram asserts that sexual violence is inherently a racial issue, having roots in slave history as a ‘tool of violence and dominance’ (26). The erasure of black voices amidst the 2017 #MeToo movement therefore displaces both the history of the movement and the individuals it was made for. The slave women who endured this violence lacked the agency to have ‘their narratives or stories reported or recounted’ (26); the black, Hispanic and Native American voices of the #MeToo movement in this seemingly ‘post-racial’ society have similarly had their narrative and stories usurped by the affluent white voice.

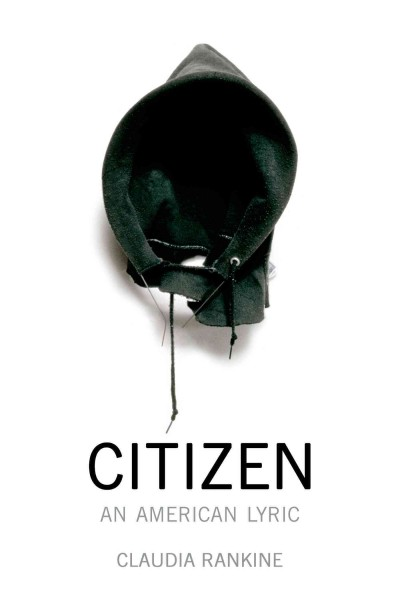

The 2017 #MeToo movement took place three years after the publication of Claudia Rankine’s book, Citizen: An American Lyric (2014), and yet the events of the movement speak to the themes explored in Rankine’s book. Her lyric is concerned with issues surrounding memory and erasure, as well as the body and violence. As early on as page 7, when describing a racial ‘slippage’ between two young close friends, Rankine writes that ‘your fatal flaw [is] your memory’. Soon after this she describes a racially charged instance between two people in a car, a moment which ‘you drive straight through…acting like this moment isn’t inhabitable, hasn’t happened before, and the before isn’t part of the now’ (10). In these instances, Rankine is interested in exploring a form a racism very different to the sexual violence enacted upon black female bodies; rather, she speaks to ‘ordinary’ or ‘intimate moments’ of day-to-day life where racism raises its head in surprise (Mormorunni 6). Rankine exposes this form of ‘casual’ or ‘acceptable’ racism as having sprouted from a deep and longstanding history of racism, rooted in slavery. As the reader works their way through, and is pulled into, these intimate and ordinary moments they become increasingly aware of the fact that the ‘before’ is still very much a part of the ‘now’; that ‘the body has memory’ (28), in fact there is an ‘historical self’ (14), and that the past cannot be put behind you as it is ‘buried in you’ (63).

Rankine is able to quite literally pull the reader into these scenarios through her ‘disorienting pronoun play’ (Mormorunni 10) where she conflates the ‘you’ and ‘I’ of the story, making her own experience ours (11). Who the ‘you’, ‘I’, ‘he’, ‘she’, or ‘they’ refers to is never quite clear, making the reader do the work to decode the scenario and further implicate the reader in their involvement in the unfolding moment. However, the pronoun play does more than pull the reader into the racist scenario: these fractured pronouns point towards a fractured sense of identity for the black individual living against ‘a sharp white background’ (Rankine 52-3). A number of times throughout the book Rankine refers to this feeling of ‘displacement’ (153), the ‘feeling [that] you don’t belong so much to you’ (146).

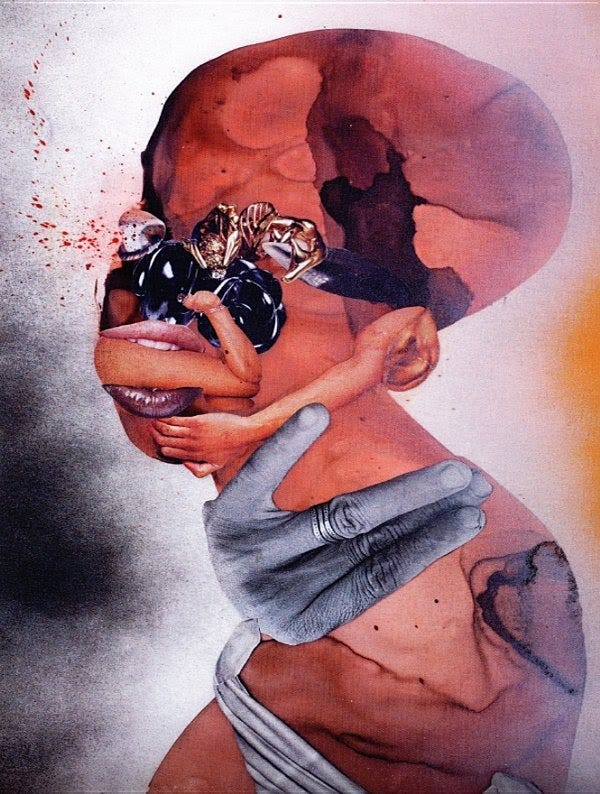

I find that this concept is best explored through the art Rankine choose to include in the book, namely Kate Clark’s Little Girl (19) and Wangechi Mutu’s Sleeping Heads (147). Rankine states that these pieces were important to her work as they ‘performed, enacted, and depicted something ancient that I couldn’t or didn’t want to do in language’ (qtd. in Clark, kateclark.com). Both pieces bring together that which doesn’t belong together, they are ‘wrong’ and appear disturbing to a certain level. Clark’s Little Girl sculpture, which depicts a black girl’s face attached to a taxidermized infant caribou, is particularly interesting to me as it speaks to a number of themes explored throughout the lyric.

The uncanny or ‘Unheimlich’ nature of the sculpture mirrors the narrator’s feeling of displacement from oneself, whilst also evoking the sense that one is hunted, weak, and defenceless. Most importantly, however, for Rankine it reminds her that her ‘historical body on this continent began as property no different from an animal’. She goes on to say; ‘So when someone says, “I didn’t know black women could get cancer,” which was said of me, I see that I am not being seen as human’ (qtd. in Clark). Ultimately, for Rankine the casual and acceptable racist ‘slippages’ that she encounters in ordinary day-to-day life cannot be detached from the longstanding history of racism that is rooted in slavery. Little Girl speaks to both the present, seemingly ‘ok’ racism that sees her as something slightly different to human, and to the brutal history of slavery, the violent treatment of black people as literal objects and animals, of which the latter stems from. (Left: Little Girl, Kate Clark 2008)

Using an array of written and visual art forms, Citizen is able to express the belief that racism is not only ever present in society but is, in its ‘lesser’ and more acceptable forms, still rooted in the legacies left from slavery. For many like Rankine, to believe in a ‘post-racial America’ is to ignore this legacy and history, as if it does not still impact the lives of those who live in a society formed from it. The usurpation of the #MeToo movement by the white affluent voice provides a contemporary example of how an inherently racial issue can be stripped of its history and thus displace the victims of that history. Rankine poignantly ends her book with The Slave Ship, pointing towards the truth that all forms of contemporary racism starts and ends with the legacy of slavery.

Bibliography

- Clark, Kate. ‘Cultural Collaborations’. USA: kateclark.com, 2022. (Online resource, https://www.kateclark.com/cultural-collaborations).

- Clark, Kate. Little Girl. 2008.

- Ram, Christelle. ‘Black Historical Erasure: A Critical Comparative Analysis in Rosewood and Ocoee Rosewood and Ocoee’. Honours Programme Thesis. USA: Rollins College, 2020. (Online resource, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors/121).

- Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. UK: Penguin Random House UK, 2014.

- Riley, Rochelle. ‘#MeToo founder Tarana Burke blasts the movement for ignoring poor women.’ USA Today News, 16 November 2018. (Online resource, https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/11/16/tarana-burke-metoo-movement/2023593002/).

- Mormorunni, Cristina. ‘The Trauma of Racism in Translation: Making the Personal Universal through Language, Point of View and a Raced Aesthetic’. USA: TerraMar, 2017. (Online resource, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://terramarconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Trauma-in-Translation.pdf)

- Mutu, Wangechi. Sleeping Heads. 2006.

- Turner, Joseph Mallord William. The Slave Ship. circa 1840.