Marie Sallé seminar

Mistriss SALLÉ toujours errante,

Et toujours vivant mécontente …

Mistress Sallé, forever wandering and forever discontented …

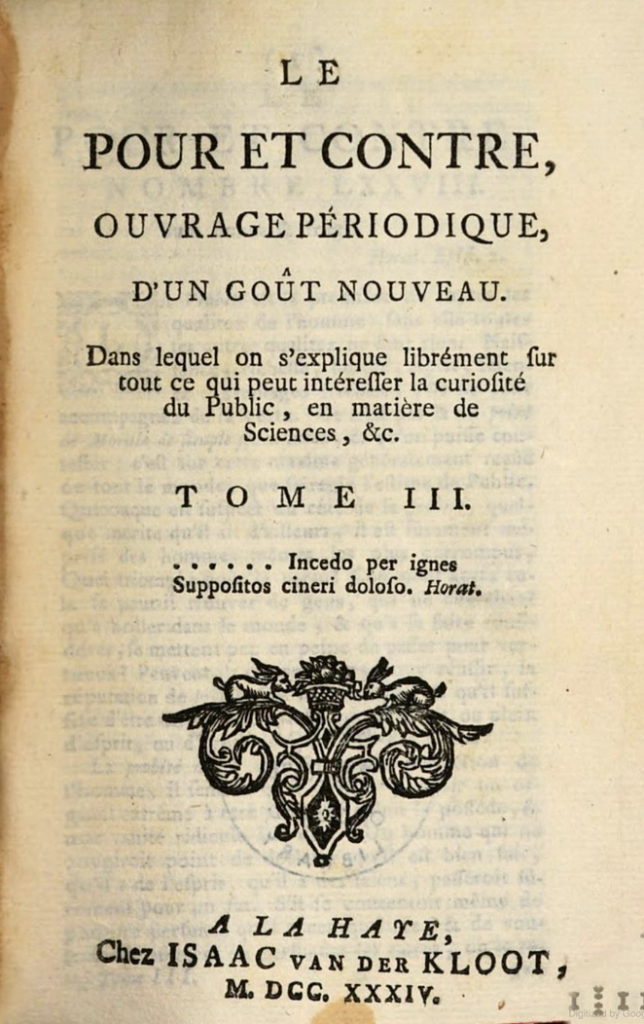

Shortly after Marie Sallé’s return to Paris in the summer of 1735, at the end of what turned out to be her last season in London, the Abbé Prévost’s journal, Le Pour et Contre, gave an account of an incident at Covent Garden that would certainly have explained her reason for leaving London in a state of discontent. This incident had supposedly occurred during a performance of the ballet scenes in Handel’s new opera Alcina, choreographed by Sallé herself:

People unashamedly hissed her [onstage] in the theatre. The opera Alcina was being performed. Mademoiselle Sallé had composed a Ballet, in which she took the role of Cupid, a role she danced in male attire. It is said that this attire ill-suits her and was apparently the cause of her fall from grace. [Emphasis added.]

On n’a pas eu honte de la siffler en plein théâtre. On jouait l’Opéra d’Alcine. Mademoiselle Sallé avait composé un Ballet, dans lequel elle se chargea du rôle de Cupidon, qu’elle entreprit de danser en habit d’homme. Cet habit, dit- on, lui sied mal, et fut apparemment la cause de sa disgrâce.1)

These events are widely assumed to have taken place at the première of Alcina on 16 April 1735; indeed, the Biographical Dictionary of Actors, following Prévost, states as a fact that on that date she was hissed by members of the rival opera company from the King’s theatre.2)

A pirated edition of Le Pour et Contre in the Hague had already published a different report of her dissatisfaction with England, followed by an epigram, two lines of which appear above as my epigraph: “Mademoiselle Sallé, unable to appear in England with the same satisfaction as before, when she received the applause of the Court and the City, has resolved to abandon the English and return to France. I am told that she has indeed left and is expected to arrive in Paris at any moment. Here is an Epigram on the subject of her return:

EPIGRAM on the Return of Mademoiselle Sallé

Mlle SALLÉ forever wandering,

And living forever discontented,

Still deafened by the sound of hissing,

Heavy of heart, light of purse,

Comes home, cursing the English,

Just as, on leaving for England,

She had cursed the French.

Mademoiselle Sallé ne pouvant plus paraitre en Angleterre avec la même satisfaction que ci-devant, lorsqu’elle recueillait les applaudissements de la Cour et de la Ville, a résolu d’abandonner les Anglais et de retourner en France. On me mande qu’elle est effectivement partie, et qu’on l’attend à Paris à tout moment. Voici une Epigramme qu’on a faite sur son retour.

EPIGRAMME sur le retour de Mademoiselle Sallé

Mistriss SALLÉ toujours errante,

Et toujours vivant mécontente,

Sourde encor du bruit des sifflets,

Le cœur gros, la bourse légère,

Revient, maudissant les Anglais,

Comme en partant pour l’Angleterre

Elle maudissait les Français.3)

This news item must have been written around mid-June (NS) because on 2 July 1735 (NS) in Paris, les nouvelles à la main [manuscript news-sheets] carried a report which appears to show knowledge of this pirated Hague edition of Le Pour et contre:

La Sallé has come back from England, as discontented with the English as she was with us when she left. Here is an epigram that depicts her perfectly …

La Sallé est revenue d’Angleterre, aussi mécontente des Anglais qu’elle l’était de nous quand elle partit. Voici une épigramme qui la peint au naturel …

The news-sheet reproduces the epigram with a slightly different second line: ‘Et qui vit toujours mécontente’ [‘And who lives forever discontented’].4) According to Prévost’s account, the hissing incident strongly suggested that Sallé, once the idol of London society, had fallen out of favour with it. This situation had been foreshadowed by other observers. In a letter of 9 January 1734 Mattieu Marais noted:

The English, who know little about dance, are growing tired of Sallé and say they had enough of her last year, and the ladies find her prissy [pimpesouée] and hoity-toity.

Les Anglais, qui se connaissent peu en danse, se lassent de la Sallé et disent qu’ils en ont eu assez il y a un an, et les dames anglaises la trouvent pimpe-souée et faisant la milady.5)

The word ‘pimpesouée’ implies a woman who plays ‘hard to get’ and it may be that Sallé’s impeccable private life was partly responsible for the ladies’ resentment of a mere dancer whose moral standards were higher than their own. In early 1735, Prévost had printed some English verses indicating that Sallé had aroused displeasure not only for her financial success but, more dangerously, for expressing a low opinion of the English:

Miss Sallé too (late come from France)

Says we can neither dress nor dance.

Yet she, as is agreed by most,

Dresses and dances at our cost.

She from experience draws her rules

And justly calls the English fools.

For such they are, since none but such

For foreign Jilts would pay so much.6)

In the following I propose to re-examine the supposed Cupid incident and suggest an alternative explanation for what happened.

First, it is important to note that, other than in Prévost (whose wording –‘it is said’ and ‘apparently’—indicates that he is writing at second or third hand), there is no reference to the Cupid incident in any other source. It is nowhere mentioned in the London press or in any contemporary French or English correspondence – including that of John Rich and the inveterate gossip Lord Hervey, who would surely have commented on it. As for the suggestion that the hissing on this occasion came from a rival company, Sallé seems to have been on good terms with dancers from the other theatres; in fact, the London Daily Post and General Advertiser had reported on 17 March 1735 that

The Celebrated Monsieur [George] Denoyer and Mademoiselle Salle, by Permission of the Masters of the two Theatres Royal, … agreed to dance together at each other’s Benefit.

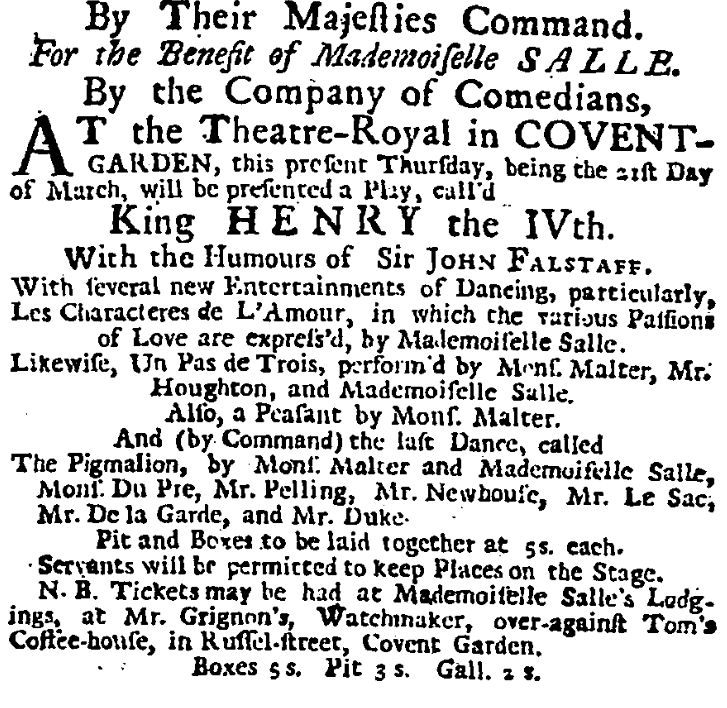

The idea that hissing could have been provoked by Sallé’s costume as one of the fluttering cupids in Alcina’s garden is, in my view, equally far-fetched. In the London seasons of 1733-4 and 1734-5, travesty roles for women in dance, often as cupids or petits-maîtres, were commonplace, as can be seen from these selections from two seasons’ playbills in The London Stage.

Covent Garden, 16 March 1734. The Nuptial Masque or The Triumphs of Cupid and Hymen. ‘Cupid – Miss Norsa, the first time of her appearing in boy’s clothes.’

Drury Lane, 18 March 1734. ‘Minuet by Mlle Grognet (in Boy’s Cloaths);’ Prince of Wales present.

Covent Garden, 18 March 1734. ‘A Courtier by Miss Norsa in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Goodman’s Fields, 25 March 1734. ‘An Epilogue of thanks spoke by Mrs Roberts in Man’s Cloaths.’

Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1 April 1734. ‘Minuet by Mlle Grognet in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Covent Garden, 6 April 1734. ‘Mrs Kilby, the first time of her appearing in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Covent Garden, 29 April 1735 ‘Harlequin by Miss Norsa Jr., the first time of her appearance on any stage.’

Haymarket, 5 May 1735. Grognet benefit. ‘The Wedding (new) by Mlle Mimi Verneuil and Mlle Grognet in Man’s Clothes.

Covent Garden, 20 May 1735. ‘Afterpiece Minuet by Mlle Grognet in Men’s Cloths, and Miss Baston.’

York Buildings, 3 June 1735. ‘A Minuet by Miss Norsa in Boy’s Cloaths and Miss Oates.’

Haymarket, 9 July 1735. Aaron Hill Zara. Epilogue spoken ‘by Miss ___ in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Click here for an image of the actress Peg Woffington in a trousers role (London, 1746).

However, in dance (as opposed to opera) this kind of travesty was almost exclusively the preserve of very young girls and women.7) It was, for example, a specialty of Manon Grognet (‘la petite grognette’ as Mathieu Marais called her in 1733), who was currently dancing in travesty as a petit-maître at the Little Haymarket Theatre – but, as Marais had written, specifically contrasting her dancing with that of Sallé, ‘it’s a different kind of dancing, and there will be enough for everyone [c’est une autre danse, et il y en aura pour tout le monde].’8) What he was surely referring to was the difference between the ‘belle danse’ of the Opéra-trained Sallé and the sprightly commedia style that Grognet would have learned at the fairs.) As an adult, Sallé (aged twenty-six in 1735) never danced in male attire, and nothing in her entire adult career in London or Paris lends a shred of credibility to the idea that this woman of impeccable taste and judgment would have played a young male Cupid, so soon after the refined grandeur of her recent ground-breaking appearances as Galatea in Pygmalion, Ariadne in Bacchus and Ariadne, a Bridal Virgin in Apollo and Daphne, and the Bridal Nymph in A Nuptial Masque.

How, then, did this unlikely story arise? I believe there may be a clue in a letter from Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, to Diana, Duchess of Bedford, dated 24 June 1735, telling of an incident which did indeed take place at Covent Garden during a performance of Alcina. The King attended performances of this opera both on the opening night, 16 April, and on 14 May with the Queen and Princess Amelia. Since nothing unseemly was reported about the opening night (it surely would have been publicly noticed then), the incident recounted by the Duchess must have taken place on 14 May. While the Duchess could not be bothered to know the name of the performer in question, Sarah McCleave has identified her as Marie Sallé:

The famous dancing woman (I do not know her name) in the opera, the audience were so excessive fond of her that they hollered out “encore” several times to have her dance over again, which she could not do, because as she was coming on again, the King made a motion with his hand that she should not. At last the dispute was so violent that to put an end to it, the curtain was let down, whereby the spectators lost all after the third act.9)

The Duchess’s letter provides evidence not only that Sallé danced in Alcina until 14 May but, more importantly, that a full month after the première of the opera, far from being out of favour, Sallé was still immensely popular. As Alcina has only three acts, the Duchess’s meaning is unclear, but it seems likely that the incident took place at the end of the second act in the ballet of good and bad dreams, probably the ‘Entrance of pleasant dreams’ [Entrée des songes agréables], which Handel borrowed from the ballet he had written for Sallé in Ariodante in January 1735. The King’s gesture was clearly one of impatience, indicating that he wanted the evening to end soon. On the following day, 15 May, he was to prorogue parliament and on 17 May he would eagerly set out for Hanover and the arms of his mistress. He had sat through two acts and his mind was already elsewhere.

As the Duchess makes clear, the audience’s anger at the King’s peremptory dismissal of the popular dancer was so violent that the performance had to be brought to an end. Hissing there certainly was, and Sallé was indeed obliged to leave the stage, not because of her costume (which audiences over the three previous weeks had already seen without comment), but, according to the Duchess of Marlborough, in obedience to a gesture from the King which most of the audience would not have seen. Could it be that the noisy outburst at this aborted performance on 14 May was thought by some (especially those who heard of it at second-hand) to have been directed not against the King but against Sallé herself when she attempted to return to the stage to take her encore? Might it even be that her entrée was not a solo and that a cupid or cupids en travesti entered with her, adding to the confusion?

This explanation may perhaps be supported by the opening of the already quoted news item from the pirated Hague edition of Le Pour et contre:

Parisians have learned with a joy that is neither shocking nor insulting to Mademoiselle Sallé, of the unfortunate accident[10] that befell her recently [emphasis added] in London, since this insult seemed to them to predict the prompt return of this famous dancer.

Les Parisiens ont appris avec une joie qui n’a rien de choquant ni d’insultant pour Mademoiselle Sallé, le fâcheux accident qui lui est arrivé en dernier lieu [emphasis added] à Londres, puisque cet affront leur semblait pronostiquer le prompt retour de cette fameuse Danseuse.

This report seems to me entirely consistent with the incident described by the Duchess of Marlborough. The report that Sallé was being less favourably received than before by the Court (the King?) and the City (the raucous audience?), makes the ‘unfortunate incident’ sound very recent, far more like the ‘violent dispute’ which happened on 14 May than something which has hitherto been presumed to have taken place on 16 April and of which there is not a single mention in the English press.

Since the Earl of Egmont, a friend and confident of both King and Queen, noted in his journal for 14 May, ‘In the evening I went to Handel’s opera called Alcina’, it might seem odd that he made no mention of any disturbance. However, earlier in the day, he had had a long discussion with the Bishop of Salisbury concerning the unstable state of international affairs, and the King’s apparent indifference to it. The Bishop warned Egmont that ‘Sir Robert [Walpole] sees his situation and is very uneasy at it, and so is the Queen. […] It is a great misfortune the King is made believe the people’s affections are warm to him, none daring to tell him the truth.’11) Egmont might, then, have found nothing newsworthy in a rowdy demonstration against the monarch and in favour of a much-loved dancer.

Sallé, however, may well have interpreted the King’s gesture as an unexpected sign of sudden royal disfavour, and she might even have taken the ensuing raucous demonstration to be directed against her rather than against the King. After the performance on 14 May there is not a single known mention of her by name in the London press or contemporary correspondence concerning the remainder of the Covent Garden season. There were altogether eighteen performances of Alcina, ending with a royal command performance for Queen Caroline on 2 July, but Sallé cannot have been dancing in London on 2 July 1735, or at any point after mid-June at the latest, for one very simple reason. What seems to have been hitherto overlooked is the crucial fact that Britain did not adopt the Gregorian revisions to the calendar until 1752, and until then the date in England (Old Style) was eleven days behind the date in Catholic Europe (New Style). Sallé must have already been in Paris well before 2 July (New Style) for the news of her arrival to reach the news-sheets and inspire the mocking epigram. The journey from London to Paris could take over a week, often ten days or more, depending on the state of the seas and the roads. This means that at the very latest Sallé must have left London around mid-June (OS) and performances of Alcina must therefore have continued without her.12) It could even be that Sallé walked out of Covent Garden immediately after the ‘unfortunate incident’ of 14 May; her ‘empty purse’ mentioned in the mocking verses would be the result of the loss of salary for the remaining nine performances. This view is supported by the fact that, when Alcina was revived, in November of the 1736-7 season, it was without either Sallé or the dances.

Sallé’s behaviour may seem an over-reaction to what might best be described as an unfortunate concatenation of misunderstandings. But it was in keeping with her hypersensitive and headstrong character. There has been no previous discussion of the fact that every one of Sallé’s seasons between 1730 and 1735 ended abruptly in some kind of irregular incident, violent altercation, and/or illness — Paris in August 1730; London in May-June 1731; Paris in November-December 1732; London in May 1734; London in May-June 1735. The nouvelles à la main dated 25 August 1730 reported that she and one of the directors (Claude-François Leboeuf) had argued on the stage of the Opéra, perhaps even coming to blows.13) In London, where she remained from November to the end of the 1730-31 season, Sallé received a glittering royal benefit on 25 March 1731. However, her name disappeared from the playbills from 3 May until 1 June, when there was a single announcement of ‘Dancing by Mlle Sallé’; then Rich’s company moved to Richmond, and Sallé, presumably, went back to France. No explanation seems to exist for this rather odd, month-long hiatus. In her letter to the Duchess of Richmond in 1731, Sallé made it abundantly clear that she did not like John Rich, whom she described as ‘a rude and unjust man at whose hands I have suffered too much ill treatment [un homme impoli et injuste, dont j’ai souffert trop de mauvais traitemens].’14) The last two lines of the epigram written about her two years later – ‘Just as on leaving for England/ She had cursed the French’ — would seem to be further confirmation of the fact that Sallé had left Paris in October 1733 in unpleasant circumstances. On 24 May 1734, Pygmalion and Bacchus and Ariadne were advertised, as ‘being the last Time of the Company’s performing this Season‘ (Daily Journal). However, according to Rich’s Register the audience was dismissed, ‘by reason Madem Sallé wou’d not come to the House.’15)

Whatever exactly happened in 1735, it is clear that the ‘unhappy incident’ (‘fâcheux accident’) was the culmination of a number of unfortunate events, and one from which she did not recover. It affected her health: Voltaire, who saw her soon after her return, wrote on 15 July to Sallé’s ardent but frustrated admirer, Nicolas-Claude Thiériot, ‘So, you are avenged; your nymph has lost her beauty [Vous voilà donc vengé de votre nymphe; elle a perdu sa beauté].’16) Sallé had not, however, lost the admiration of audiences in both countries. The pirated Pour et contre had recorded the ‘joy’ with which Parisians looked forward to her return:

It is not yet known whether she will dance at the Opéra, and the public display an impatience about this which does her credit.

On ne sait encore si elle dansera à l’Opéra,et le public témoigne là-dessus une impatience qui lui fait honneur.

The Daily Journal of Tuesday 5 August (OS) reported that, to the delight of all Paris, Sallé was to dance in the new opera Les Victoires Galantes, the original title of Fuzelier-Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes, premiered on 23 August 1735 (NS). It added,

We do not mind what shall be done upon the Rhine by Marshall Coigny, or in Lombardy by Marshall Noailles, but what Mademoiselle Sallé will perform on the stage of Paris.17)

The fact that her activities were the object of so much speculation may simply be the result of her ‘celebrity’ status, enhanced by prurient interest in the ‘virtue’ (i.e., chastity) of a mere dancer and perhaps also by the very unpredictability that I have been describing. Judges as severe as Voltaire seem to have been charmed by her charismatic personality. Proof that she still had a loyal following in London is suggested by the report in the Grub Street Journal for 19 August 1736 that Desnoyer, ‘the famous Dancer at Drury-lane theatre,’ had gone to Paris ‘by order of Mr. Fleetwood [the theatre manager]’ to try to hire Sallé for the winter season – something that certainly does not suggest any dimming of her star. But the hopes of Desnoyer and Fleetwood were to be disappointed.

Did Sallé ever return to England? Dacier notes that some of her contemporaries thought this, though he could find no evidence of it.18) An unsubstantiated and uncorroborated account, written some ten years after the event it claims to describe, was included in an anonymous article (Mémoires d’un Musicien) which appeared in three numbers of the Journal Encyclopédique in May-June 1756, just a month before Sallé’s death in obscurity:

Mlle Sallé, the French dancer in whom the most respectable morals were united with the rarest talents, caused admiration on the London stage for graceful qualities which the English had not hitherto seen, and which are created and acquired only in France. I had known her there; she seemed most content to receive me, and I was witness to her unhesitating sacrifice of over a thousand louis which ought to have accrued from her engagement with Handel, even though she was solicited by the greatest lords in London to break it off, which a caprice led them to speculate would be more desirable.

Mlle. Sallé, Danseuse Françoise, qui scavoit unir les moeurs les plus respectables aux plus rares talens, faisoit assez admirer sur le Théâtre de Londres des graces que les Anglois n’avoient pas encore connues, & qui ne naissent, & ne peuvent s’acquerir qu’en France. Je l’y avois connue, elle parut fort aise de me voir, & je fus temoin du sacrifice qu’elle n’hésita point de faire de plus de mille Louis qui auroient dû lui revenir de son engagement avec Hendel, quoique sollicité par les plus grands Seigneurs de Londre de le rompre, pour en prendre un nouveau avec un entrepreneur qu’un caprice leur faisoit esperer plus agréable.19)

In a 1996 article by David Charlton and Sarah Hibberd, these few lines became the subject of scholarly speculation on the possibility of Sallé’s return to London, a discussion taken up and amplified by Sarah McCleave.20) Whatever the facts of this matter may be, one thing is clear: after leaving London in June 1735, Marie Sallé was never again to dance on the English stage.

Dr Robert V Kenny is Honorary Fellow in French Studies in the University of Leicester. His full-length study of Sallé’s uncle François Moylin (Francisque) and his travelling theatre companies in England and France will be published by Boydell and Brewer early in 2025.

The next post will be a report on an aspect of Sarah McCleave’s ‘Fame and the Female Dancer’ project.

Lola Montez stimulated a considerable posthumous cultural legacy, remaining a subject of interest in places where she’d lived and performed (including Germany, France, USA, Australia) – but also in places she’d never been. This blog post will highlight a small selection of the works in various media inspired by this controversial performing artist.

Coverage of Montez in the press throughout the 1860s remained fairly intense. The London-based weekly, the Era, had by the time of Montez’s death become a regular source of information on all matters theatrical. Its two-column obituary of Montez (10 February 1861), reproduced from the New York Herald of 21st January demonstrates the range of response that Lola inspired. This obituary was swift to point out her personal faults (“Lola … managed to quarrel with everybody she met”), and to dismiss her skills as a performer (“As an artist she was good for nothing.”). Her début at New York’s Broadway theatre took place “to a crowded house, nearly all men. Everybody was disappointed in her dancing and appearance.” Such was the culture of the time that even Montez’s thinness was cast as a moral issue, a product of her “fast living and incessant smoking”. The Herald/Era is most positive when discussing Lola’s career as a lecturer, as she “attracted large audiences, her manner being very prepossessing, and her delivery excellent.” It also recognized that “Lola was very generous to people about her, and would share her last meal with a friend.” Indeed, at her untimely death Lola was surrounded by friends who “cared for her, and mourned her loss”.1)

Montez had the perfect combination of qualities to sustain her celebrity status: some sympathetic attributes, some marked personal flaws, and a tremendous charisma combined with enough capacity as an entertainer to make herself known in the public sphere. By the end of the decade, she was remembered in a nostalgic manner by Paris’s Le petit Figaro, which in its gossip column (“Causeries”) of 22 June 1869 cast her as “une pauvre errante” (a poor erring one) and the leading player in a piece on actresses who’d managed affairs with royalty. In reviewing her Paris years, it suggested Lola’s engagement as a dancer at the Porte de Saint-Martin was secondary to the negative role that she, as a beautiful woman, was obliged to assume — of selling her charms (“Elle … vendu ses charmes au plus offrant … pour en venir jouer un de ces rôles negatifs dans nos théâtres. Singularité de la vie des belles.”) Of her Bavarian sojourn and subsequent exile, the paper tartly observed that to keep a single, defenceless woman out of the region the garrison’s forces at Munich were doubled.2) And so Le petit Figaro mentions Lola’s capacity to wreak havoc while poking fun at authority for its overblown response to her. In effect, the Parisian press (as did the Anglo-American) traded in on Montez’s fabulous life to generate material, but did not feel so obliged to adopt the moral high ground. As for the Antipodean press, the name of Lola Montez generated the most coverage during her decade as a traveling dancer (the 1850s, some 1000 references), with a similar level of exposure in the decade of her death.3)

As was the case in her life, so it was in death: any purportedly biographical publication about Mme Montez was assuredly a blend of the fictional and of her equally fabulous reality. The tone of the publications reflected the nature of the society in which they were generated — and the role Lola played within that milieu. And so in Germany during or shortly after her Munich period a study of her relationship with the Jesuits, and also of her political significance, came out in print.4) In America – where as a fervent Christian Lola spent her final months in relative seclusion and sobriety – within six years of her death the Protestant Episcopal Society for the Promotion of Evangelical Knowledge had published The Story of a Penitent: Lola Montez. By the early 20th century her persona as an adventuress held a particular appeal in the Anglophone world — as her place within William Rutherford Hayes’s 1908 biographical compilation Seven Splendid Sinners suggests.

Lola has also stimulated a considerable number of creative works in a range of media. Novels, films, a musical, and songs dating into the second decade of the 21st century demonstrate her abiding capacity to generate interest. Some of these works draw on her actual adventures; others create entirely fictional episodes that use the name of Lola Montez to represent an uninhibited adventuress.5)

Sometimes one work might spawn another in a different medium. In 1918 Robert Heymann (1879-1946) adapted and directed a silent film “Lola Montes” on a novel by Adolf Paul (1863-1943), with Leopoldine Konstantin (1886-1965) in the title role. Paul’s novel also led to further Lola-inspired films including The Palace of Pleasure (1926; directed by James Flynn) and Lola Montez: One mad kiss (1930, directed by Marcel Silver and James Tinling). Max Ophuls’s final film, Lola Montès of 1955 is described on YouTube as “a magnificent romantic melodrama, a meditation on the lurid fascination with celebrity, and a one-of-a-kind movie spectacle” (criterioncollection). The trailer gives us a wonderful glimpse of incidents many of which would not have had to rely on fiction, although Lola’s stint as a circus performer in the film was imagined rather than quasi-biographical. Indeed, ‘The Circus’ has become the title for a suite of music by Georges Auric from the film.

A 1958 musical with music by composer Peter Stannard and lyrics by Peter Benjamin was broadcast on Australian television in 1965, with a particular hit in the song ‘Saturday Girl‘; a CD was released in 2000, with a one-off 60th anniversary production in 2018 by David Spicer. Lola has also inspired the occasional popular song from musicians working in markedly different styles — including the ‘Latin Folk Exotica’ of Elisabeth Waldo’s 1969 ‘The Ballad of Lola Montez‘ on her Viva California album and the groove metal number ‘Lola Montez‘ on Volbeat’s 2013 album Outlaw Gentlemen and Shady Ladies (Universal). In 2017, an acoustic folk concoction ‘The Countess Lola Montez’ was written and performed by Norman and Nancy Blake on Brushwood Songs and Stories (Plectrafone Records).

Lola Montez has attracted and sustained this attention due to her unconventional personal life and behaviour; her characteristic audacity and flair would also have lent sparkle to her performances on stage. The compelling stories surrounding this difficult but fascinating woman have created and sustained her celebrity for over 150 years.

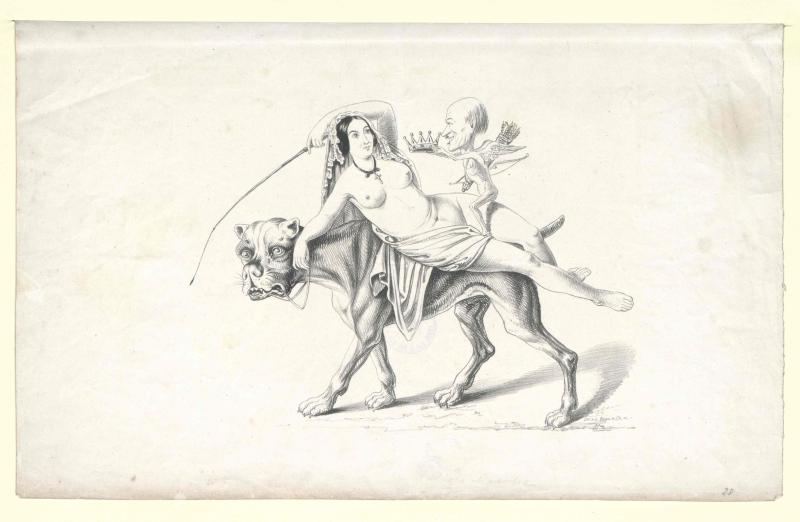

A naked Lola Montez dominating the dwarfed King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Artist not identified. Austrian National Library, Austria – Public Domain. Europeana.

The next post will report on the progress of Fame and the Female Dancer.

The first known reference to Lola in the Antipodean press marked one of her violent escapades – an event that nearly landed her in prison. Under the title ‘A Dancer in Trouble’, The Australian for 24 August 1844 inaccurately described our subject as the nineteen-year-old Mlle Montez, a Spanish dancer and the daughter of a deceased Spanish General, “who has for some time been much admired … for her great talent, is likely to be put in prison for some time.” Whilst in Berlin she attended the ‘grand Review’ on horseback, and when her horse was alarmed by some firing and “rushed amongst the suite of the two sovereigns”, she reacted badly to a gendarme who had struck her horse a blow with his sabre – striking the man across the face with her whip. Lola was subsequently issued with a summons that she reportedly (according to this ‘Letter from Berlin’) tore up. Lola was then arrested “for having manifested marks of disrespect to the orders of justice” – a charge which could have carried a sentence of 3-5 years’ imprisonment. The Adelaide Observer (12 October 1844) repeated the tale in a section of material on ‘Spain’. For nearly three years thereafter the Antipodean papers apparently chose not to run stories concerning Mlle Montez – until she elected to pen a letter concerning her origins, originally addressed to the Paris-based publisher Galignani. This missive found its way into The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser of 25 August 1847:

I was born in Seville in the year 1823. My father was a Spanish officer in the service of Don Carlos; my mother, a lady of Irish extraction, was born at the Havannah, and married for a second time to an Irish gentleman, which I suppose is the cause of my being called Irish, and sometimes English, ‘Betsy Watson ,’ ‘Mrs James’, &c. &c. I beg leave to say that my name is Maria Dolores Porres Montes, and I have never changed that name. As for my theatrical qualifications, I never had the presumption to think I had any; circumstances obliged me at a more advanced age than usual, in consequence of the misfortunes of my family, to adopt the stage as a profession – which profession I have now renounced for ever, having become a naturalized Bavarian, and intending in future making Munich my residence. …

Lola Montez, Munich, March 31. [1847] as reproduced in https://trove.nla.gov.au/, accessed 15 July 2023.

The Maitland Mercury distanced itself from presenting this letter as factual reportage, asserting “We do not answer for its authenticity.” (Indeed, the sterling archival research of Bruce Seymour has established beyond doubt that Lola’s origins were 100% Anglo-Irish.1) But as a crafted story of origin this is intelligent in addressing inconvenient biographical details (her identity as ‘Mrs James’ is explained away) while making a bid for her readers’ sympathy (“I never had the presumption … in consequence of the misfortunes of my family …”). Lola is distancing herself from her theatrical career – possibly trying to open doors that would be closed to a mere actress – but subsequent events pushed her back onto the stage, probably not at all unwillingly.

Lola’s connection to king Ludwig I of Bavaria and a series of Bavarian scandals which she generated excited much press coverage in the late 1840s; typical is an oft-repeated report of 32 persons arrested for creating a disturbance when Lola, forced to leave Bavaria as its revolution erupted, passed through Hamburg.2 In Australia, Lola’s consequent celebrity status is affirmed when The Sydney Morning Herald (first among many broadsheets to do so) advised its readers of

Handsomely Framed Engravings Just Landed, in Salacia. Mr Edward Salomon, will sell by auction, at his Rooms, George-Street, Tuesday May 30, at 11 o’clock … [including] Lola Montez – a beautiful engraving in maple and gold frame …

Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 1848 in https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/

This was followed by another well-circulated report of king Ludwig’s abdication “into temporary retirement with Lola Montez” (The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 July 1848). The inaccuracy of this story was revealed before the month was out, as the Hobart Courier for 29 July 1848 – under the heading ‘Lola Montez and her new admirer’ – recounted her association with Robert Peel 3rd Baronet, “our Charge d’Affaires in Berne”, with whom Lola – described as a “fair and fiery fury” – is seen promenading on a daily basis, followed by a varied train of gentlemen, girls, and children. Peel, with an “aim to be conspicuous” surely equaled by the object of his admiration, even hosted a dinner for her to which the English ambassador had been invited.

Montez’s bigamous marriage with George Trafford Heald was the next event to receive multiple coverage, led by The Sydney Morning Herald on 20 November 1849. By 11 January 1850 the Melbourne Argus broadcast Lola’s origins as Miss Eliza Gilbert, a former attendee of a boarding school in Monkwearmouth (Sunderland). Eliza’s former drawing teacher Mr Grant remembered a “beautiful and elegant child”, but one who demonstrated an “indomitable self-will”. This revelation did not prevent the Irishwoman from being received as the persona ‘Lola Montez’ when she arrived in Australia some five years later – although the Argus would maintain a critical stance in its subsequent coverage of her. The Antipodean press was engaging with Montez as a personality rather than as a performing artist – until The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser for 13 August 1853 reprinted a review of one of her Californian performances as ‘American News’. The level of interest that Montez could generate on a stage is evident in this account:

Seldom is actress or artist greeted with such a house as was the renowned Countess of Landesfeldt last evening at the American. The building was literally stowed with human beings. …the people … were impatient till [Lola Montez] appeared. In the character of Yelva, Madame Lola’s powers of pantomime were exhibited, and she portrayed the sufferings of the orphan with a great deal of truthfulness and effect … Following this came … the Dance. The dance was what all had come to see, and there was an anxious flutter and an intense interest as the moment approached … She was greeted with a storm of applause, and then she executed the dance, which is said to be her favorite, and has won for her much notoriety. The Spider Dance is a very remarkable affair. It is thoroughly Spanish, certainly, and it cannot be denied that it is a most attractive performance. As a danseuse, Madame Lola is far above mediocrity. Indeed, some parts of her execution was truly admirable. She was heartily applauded … [and] is sure to have fine success with us …

Alta California of 28 May, reproduced 13 August 1853, found in https://trove.nla.gov.au/.

Australia, by finally acknowledging Montez as a performer, joined other nations in expressing a fascination with her pièce de resistance – the Spider Dance. In 1853, a ball organised by G Pickering of Sydney promised “all the late polkas – and especially Lola Montes’ Spider Dance, which is just now creating such a sensation in Europe and California.”3 Lola brought this sensation to Australia in the latter months of 1855; the sensations that the Argus of Melbourne (20 September) chose to record were shock (“a public exhibition of this kind”) and moral condemnation – the latter directed at any of the theatres who chose to let Montez perform (“they have no right to insult respectable ladies by inviting their attendance”). The Hobart Courier (25 September 1855) gleefully reproduced this journalistic exemplar of moral outrage alongside an eloquent letter Lola had penned in response, in which she reasonably pointed out that the tarantella is a national dance performed by all classes of Spaniards; she is not attempting to cater for a “morbid taste for immoral representations”, but rather views the dance as a piece of “high art”. Montez’s readiness to engage with the press and her skill at identifying the best possible angle from which to present herself promoted her fame as a professional in tandem with renewing her status as a celebrity. In the image below Adelaide-based artist John Michael Skipper (1815-1883) depicts Lola the professional rendering the Spider Dance with vivacity and grace. The featured image for this blog is the same artist’s take on Lola the celebrity – engaging in the provocative act of being a woman who dared to smoke in public.

And yet Lola’s departure from San Francisco for Australia on the Fanny Major (6 June 1855) with a self-assembled theatre company apparently had generated no press coverage at her destination.4 Her Antipodean coverage picked up suddenly and in a sustained manner from 23 August 1855, with her company’s début performance at the Royal Victoria theatre, Sydney, in “the deeply-interesting drama”, Lola Montez in Bavaria (Sydney Empire, 23 August 1855). Lola gained a favorable review for her acting from the Sydney and Sporting Review (25 August 1855), which opened by remarking: “This extraordinary and gifted being made her appearance … before the most crowded audience that was ever jammed into the Victoria.” Noting that her notoriety did not prevent her from eventually winning over a “particular” American public, the paper continued by observing,

the Lola Montes of reality, [is] a different personage fromthe Lola Montes of notoriety.Her entrée was modest and elegant, and throughout the long performance she played with a mingled fervour, grace, playfulness, and pathos that fully gained the favour of all.…. We glory in the boldness of the woman who … challenges her tale to be gainsaid.She not only vindicates her character during that particular career, but appeals to history to confirm her statement …

Reproduced in https://trove.nla.gov.au/, accessed 14 July 2023.

Lola invariably attracted partisan press coverage, in large part because her celebrity status permeated nearly every account we have of her. Her Antipodean period saw performance successes and failures, the rupture of many professional alliances (she broke with her original company some months into the tour), and the tragic loss of her married lover the actor Frank Folland on the return journey to the USA.5 On her arrival Stateside Lola cultivated a profile as a public lecturer. In this pursuit she was quite successful, as her capacity to engage and fascinate was in this format perhaps less compromised by technical limitations (as compared with her dancing or acting). Lola’s final American years were also marked by her fervent interest in Christianity, by accelerating poor health, and an early death on 17 January 1861 in New York City. Despite the sad brevity of her existence, the eventful life and career of ‘Lola Montez’ continued to exert a fascination that is still evident in our own time.

The next post will consider the posthumous reception of Lola Montez.

Lola’s determination to try her luck in America demonstrated her capacity to take on new challenges and her quest for adventure. In her initial four-year sojourn to that country (1851-1855), she traversed a goodly span of the still-expanding United States, developing her skills as an actress and a lecturer while still remaining active as a ‘Spanish dancer’. This blog will focus on the kind of reception she attracted, particularly in the print media.1) Lola had already been an occasional subject of interest in the American press since her London début, where her persona as a “Spanish danseuse who has created a great sensation” was lauded for demonstrating a “bewitching” softness and suppleness (Daily Evening Transcript, Boston, 29 July 1843). Symptomatic of her status as a celebrity, Lola received more intense coverage during her turbulent period in Munich. Philadelphia’s Public Ledger offered a terse account of the Munich riots that served mainly to apportion blame:

Lola Montez the dancer, by her impudent conduct and unpopularity, has occasioned a riot at Munich which compelled her to leave.2

Public Ledger (Philadelphia), 20 March 1848

Lola’s peregrinations since fleeing Munich eventually led her to Paris by late March 1851. She subsequently prepared her return to the stage, placing herself under the tutelage of dancer turned impresario Charles Mabille, who choreographed a tarentella as well as Bavarian, Hungarian, and Tyrolean dances for her. She made important contacts with Americans such as Edward Payson Willis, younger brother of the editor and author Nathanial Parker Willis; Lola also intrigued James Gordon Bennett, editor and publisher of the New York Herald – who would lead his peers in providing Montez with what amounted to free publicity throughout her American period. The younger Willis had encouraged Lola to make an American tour; she duly made provision for this when, on 26 August 1851, she signed a six-month contract with the Parisian-based agents Roux et cie (later reneged in favour of Payson Willis). On 12 September Lola offered a private preview of her repertory at the Jardin Mabille, before undertaking what would be her final European tour through parts of France, Belgium, and what is now Germany.3)

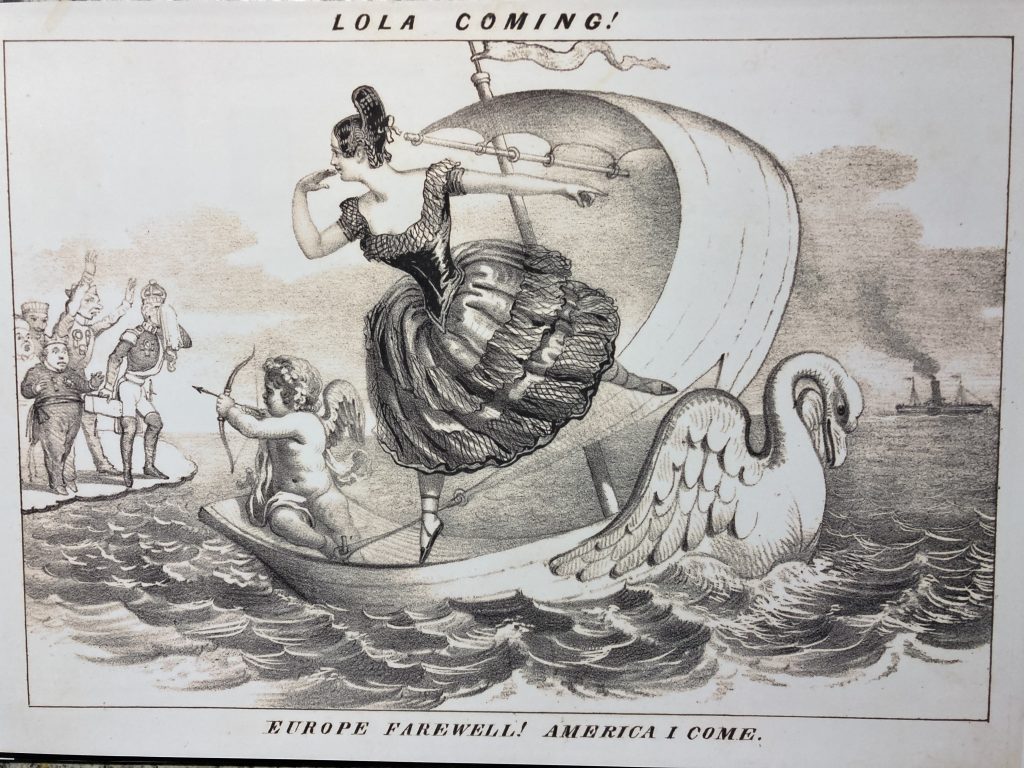

Lola’s arrival Stateside was already anticipated. On 22 August 1851, the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel and Gazette dismissed her as a “notorious courtesan concerning whose probable visit to this country much has been said of late”. By the time Lola had disembarked the Humboldt in New York city on 5 December 1851, her arrival had also attracted the attentions of thespian-turned-caricaturist David Claypoole Johnston (1798-1865). Johnston was inspired to comment on Lola’s capacity to disrupt and to stimulate through a pair of images: directly below we have ‘Lola coming!’ which depicts a pert dancer aloft a departing boat, cheerily saluting a group of variously stunned or bereft men of high station, including an openly distraught king Ludwig (presumably the weeping figure with handkerchief).

Johnstone also marked Lola’s arrival with ‘Lola is come!’ (see featured image, above). News editor Bennett takes pride of place to our right, in what would have been the best seat in the house for enjoying Lola’s “bewitching” postures up close — and for determining whether she sported knickers or not. We have an anonymous puritan in the audience, showing both disapproval (through the tract in his hand) and fascination (the expanded iris of his one visible eye as he stares through his fingers at the audacious dancer). It is not known whether the stage manager to the left – keenly anticipating his acquisition of 50% of the proceeds – is Broadway Theatre manager Thomas Barry (at whose theatre Lola made her American début on 29 December 1851) or merely a figure representative of his profession.4)

Lola’s performances attracted both advance notices and reviews in the press. Of the latter, one of the more favourable notices lauded her “great ability” in the pantomime sections of the ballet, Betley the Tyrolean, claiming Montez the equal to the “versatile and expressive mime artist” Céline Céleste. (Céleste had toured the US on several occasions, most recently in 1851.) 5) Montez’s dancing made an impression as “decidedly unique and original”; her acting displayed a capacity to make an ungratefully-written character appear interesting although her voice lacked projection in its upper range. As to her person, Montez of the “remarkably beautiful” eyes also possessed a “good” figure, “incomparably graceful” action and a “most radiant” smile. (The Mississippi Free Trader, 26 January 1853). On 19 January 1851 , the same paper had already reported on Lola graciously sharing the tributes and bouquets of an enthusiastic audience with her colleagues; this action endeared her to the audience still further.

Tonight she will perform a pas seul … [she] will be original. She copies from no one; she is herself alone.

Mississippi Free Trader (Natchez), 19 January 1853, p. 2

Whether Lola’s authenticity as a performer was mirrored in her off-stage persona is debatable. The generosity she displayed on the Natchez stage may have been calculated to stimulate positive publicity, but if so was certainly not a one-off: the “much beloved” Lola had been reported offering “unbounded” acts of charity to the poor whilst resident on Lake Geneva in 1848; in 1852, she offered a charitable performance for the Disabled firemen at Philadelphia’s Walnut theatre. For the latter act she was rewarded with a formal presentation that was duly recorded in the press.6) And while her regrettable temper underpinned her most audacious actions – including her tendency to brandish whips, pistols, or poison when editors or theatre managers treated her unfavorably 7) – she also demonstrated genuine courage, as this anecdote regarding an encounter with a group of army officers reveals:

Lola Montez is bound to keep herself before the public. It is related that while she was in Montreal she visited a well-known confectionary establishment on Notre-Dame street, and while there was annoyed by the entrance of several young army officers, who, under the pretence of buying something, gazed pertinaciously and unpleasantly at her. After submitting awhile, Lola walked up to the mistress of the saloon and asked, “Madam, how much do these persons owe you?” Her only answer at first was a look of surprise, but on the question being repeated, she was told “One shilling and sixpence.” “Here it is, then,” said Lola, “I would not wish that these gentlemen should lose a single copper in gratifying their curiosity by staring at me.” The officers retreated in confusion.

Lowell Daily Citizen and News (Lowell, Massachusetts), 22 October 1857, p. 1

This tale also shows Montez harnessing her capacity to be unconventional to good effect: the socially aggressive officers could not have anticipated her response, nor could they find any answer to it apart from retreat. Within weeks of her arrival, a Milwaukee-based journal offered the following evaluation of Montez’s character:

She is daring, reckless, if you will, and is unwilling to be bound down by the ordinary rules of the social compact. If a gentleman should insult her, she would shoot him, and not expect any one to do it for her.

Wisconsin Free Democrat, 21 January 1852

After four years supporting herself while cultivating her celebrity status in the United States, on 6 June 1855 Lola left her final residence in San Francisco for pastures new — boarding the Fanny Major bound for Sydney.

The next post will consider Lola Montez’s reception in Australia.

The 1820 birth in Limerick of a daughter, Eliza Gilbert, to the recently-wed 14-year old Eliza Olivier and ensign Edward Gilbert would seem to augur nothing more than the swift maturation of a very young mother. And yet Eliza the younger would grow up to become one of the most notorious actress-dancers of the mid-nineteenth century. By adopting an entirely spurious Spanish identity as Lola Montez, this flamboyant Irishwoman cultivated an unconventional performance style and a completely unfettered persona both on and off stage. Her subsequent travels across three continents left a trail of abdication, bigamy, and scandalised spectators in her wake, exerting a fascination on the press and the public that has retained some traction even into the twenty-first century. This first in a series of blog posts will cover her youth and European career.

Eliza’s metamorphosis into the famed Lola Montez could not have been predicted. She was not born into a theatrical family – indeed, her mother, Eliza the elder, was the youngest of four children born of the Cork-based M.P. Charles Silver Olivier and one Mary Green. Olivier married an heiress the year Eliza was born (1805), but arranged that she and her elder sister were bound to a milliner so they could support themselves. Eliza instead fell for the British officer Edward Gilbert, whose own origins are unknown – but in any case his family had no contact with his young wife or daughter, for he and his young wife remained in Ireland until the toddler Eliza was around three years of age, at which time Gilbert arranged to join the Forty-fourth Foot Regiment in India. He would die shortly after arriving in India; in 1824 the widowed Eliza -married a young Scottish lieutenant, Patrick Craigie. Craigie’s posting to Meerut near Dehli in 1826 was the catalyst for sending the child Eliza back to Britain, where she would be cared for by Craigie’s family in Montrose, Scotland. From that time, the young Eliza had a fairly conventional upbringing including periods at different boarding schools. She would not see her mother again until 1837, when the latter arrived to collect her from a school in Bath with a view to taking her back to India to arrange a marriage from within Craigie’s regimental contacts.1) But the teen-aged Eliza instead eloped with a shipboard acquaintance of her mother’s, the lieutenant Thomas James. This marriage did take her back to India for a spell, but the couple were deeply incompatible, and the young Eliza fled what had become a violent union to return to Britain in October 1840. Her shipboard romance with George Lennox (nephew of the Duke of Richmond) was sufficiently public to ruin Eliza’s reputation before she arrived in London — where they carried on the affair until the summer of 1841. Thomas James would consequently sue Eliza for divorce – on terms that did not permit her to re-marry.2)

As a divorced woman, Eliza James’s prospects at that time were few, particularly given her tattered reputation. In 1842 she undertook study in acting, and then dance, with a view to a career on the stage. Her decision to specialise in Spanish dance – which saw her travel to Cádiz to further her training in that national style – acknowledged the impracticality of developing the necessary skills of a classical ballet dancer given her age.3) She returned to England in April 1843 with an invented identity as Maria Dolores de Porris y Montez, using her powers of manipulation to gain the sympathy of James Howard Harris 3rd Earl of Malmesbury, who lobbied theatre impresario Benjamin Lumley of Her Majesty’s Theatre London to feature Signora Montez on his stage. Lola made her stage début in London on 3 June 1843, in a carefully prepared début that saw Lumley invite the critic of the Morning Post to a rehearsal to garner support.4) Lola was duly given an advance billing in that paper (3 June 1843) as being “of the Teatro Real in Madrid”. The London Standard (5 June 1843) also gave a favorable review, describing the dancer as “the perfection of Spanish beauty” before describing her performance of a pas de caractère entitled ‘El Oleano’:

Presently this Andalusian Papagena lifts her arms, and the sharp merry crack of the castanet is heard. She has commenced one of the dances of her nation, and many a picquant grace does she unfold. She seems to extemporise a series of beautiful gestures. each delineating some saucy fancy, and involving a grouping of the limbs charmingly harmonious in design. Now she is haughty, scornful, and assuming, with her figure erect and majestic — now does she stoop on one knee and curve her arms in laughing, mockery over her head. She stamps pettishly with her foot, advances eagerly, then recoils– described quaint half circles with her foot, and archly salutes the house by tapping her castanets merrily together. As a matter of course she is encored, and the second dance appears, if possible, more capricious and prettily wilful than the first.

Standard (London), 5 June 1843, from 19th Century British Library Newspapers.

The critic went on to locate the débutante’s skills within the then-current schools of theatre dancing:

She is evidently a superior pantomimist, and understands the expression which may be evolved by bodily actions and the gesticulation of the limbs. Her play with her arms is quite beautiful, and the inflection of her wrists is free and graceful in the extreme. There is nothing angular in her posturing; her frame seems subservient to an artist-like will, and a suggestion is embodied with an immediate definition of elegance. Such an exhibition as El Olano [sic] of course does not develope [sic] the qualities of exhibitory dancing; it is essentially a pas de caractere, and its requisitions are of the body rather than of the feet; but it may be presumed that the dona has accomplishments even in this direction worth looking at. She has not quite the refinement of Fanny Elssler in her mode of executing the character steps, but she has an equal bouyancy [sic] of manner, and can present phases of satire and frolic to the eye just as happily. We have yet to see whether the comparison may be continued as regards the solemnities and activities of a pas seul …

Standard (London), 5 June 1843, from 19th Century British Library Newspapers.

All too soon Lola’s identity as the infamous adulteress Mrs James was recognised, and Lumley withdrew his support. Lola subsequently travelled across Germany – lobbying theatres and members of the nobility directly to gain opportunities to perform. She was a unruly guest to Prince Heinrich of Hamburg before moving on to theatres in Dresden and then Berlin.5) On her return to the German principalities from Warsaw and St. Petersburg she had a brief dalliance with the celebrated composer and pianist Franz Liszt (1844).6) Lola performed very briefly at the Paris Opéra, and also at the theatre Porte St. Martin. Attempts to establish herself in Paris were limited by her lack of technical capacity although her beauty and capacity to entertain were admired.7) Le Ménestrel was prepared to describe her appearances elsewhere as ‘successes’ and to acknowledge the preparations she made towards her 1844 début:

Mlle Lolla Montez se préparer par un travail de tous les jours sous la direction de M. Maze, ancien premier danseur de l’Opéra, à de nouveaux débuts. Cette second épreuve vaudra sans doute à la jeune et belle danseuse la confirmation des succès de Pétersbourg, Varsovie, Lisbonne, Londres, Berlin et Dresde. — Paris ne voudra pas avoir tort contre tant de capitales.

Le Ménestrel, 18 August 1844, p. 4 in RetroNews: La site de la press de BnF.

Lola’s prospects improved when she embarked on an affair with the influential journalist Alexandre Henri Dujarier, but her Paris interlude ended in tragedy when Dujarier was killed in a duel (March, 1846).8)

Lola then left Paris for the spas of central Europe, encountering Lizst again in Bonn. After an affair with diplomat Robert Peel ran its course, Lola formed the intention to seek employment in the theatres of Vienna. En route, she stopped in Munich – trusting that the 1846 Oktoberfest would yield some interesting opportunities.9) Here her conversational wit and her beauty utterly captivated King Ludwig I, and what was meant to have been but a brief sojourn extended to nearly 18 months, during which Lola did little dancing but spent rather more time stirring up social strife after Ludwig commissioned her portrait from Karl Joseph Stieler for his ‘Gallery of Beauties‘, installed her in a residence on the Barerstraße, and granted her the title of Countess of Landsfeld. By February 1848 Lola was driven from Bavaria, having been pursued by angry rioters incensed with the level of influence they perceived her to have over their King. By mid-March Ludwig I had abdicated, but his hoped for reunion with Lola was never to take place. Lola would eventually settle in Geneva for some months, before departing for London in November.10)

Unable to resume her theatrical career in city where her true identity was known, Lola eventually met a wealthy man eight years her junior, George Trafford Heald, and within weeks had contracted a bigamous marriage (on 19 July 1847) using her adopted identity. The resultant scandal compelled the couple to flee to the continent, but within three years they had parted ways (July 1850).11) Lola then sought to support herself through writing her memoirs (1851). She was also forming a plan to conquer America.

The next post will consider Lola Montez’s reception in America.

Marie Sallé (1709-1756) was an acclaimed French dancer who performed and created dances in venues as disparate as the Parisian foires, the patent theatres of London, and the Paris Opéra. She was the subject of a few portraits, two of which are of interest for the ways in which they were re-purposed after her retirement as a performer.

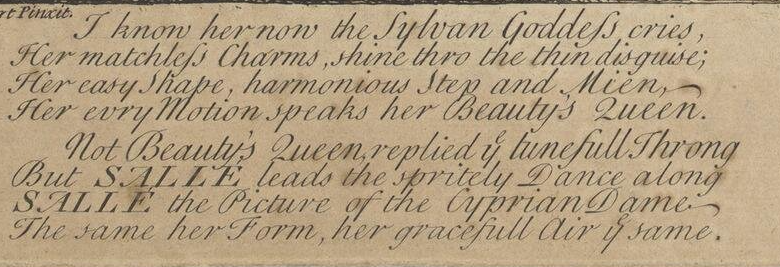

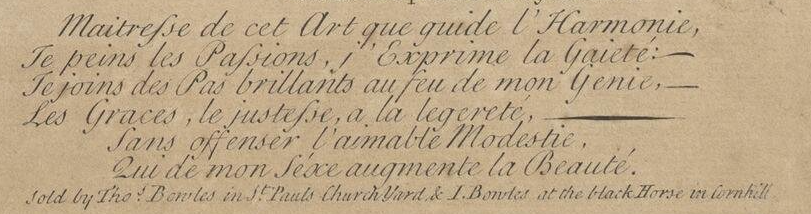

In 1732, after Sallé had reached the status of principal dancer at the Paris Opéra, her portrait was drawn by the fashionable artist Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). The Sallé painting was engraved and published by Nicolas de Larmessin (1684-1755), at that time the French royal family’s official portraitist. Lancret places Sallé within a ‘genre scene’ rather than producing a traditional portrait. Sallé, holding an attitude with great elegance, is in an outdoor setting that includes a temple of Diana on one side and a bevy of accompanying dancers on the other. Why the temple of Diana? According to James Hall, ‘the stern and athletic personification of chastity, is only one aspect of a many-sided deity’,1 but it is most probably the aspect being evoked here. Lancret’s subject is not a reference to any known role of Sallé’s, but rather promotes her carefully cultivated personal reputation.2 Voltaire – who supported Sallé by writing letters of introduction for her during the early years of his own career – wrote about this portrait in his correspondence to the writer Nicolas-Claude Thieriot during April-May of 1732. Voltaire saw the portrait in Lancret’s studio,3 and expressed a general dissatisfaction with the English verse attached to it by John Gay and Alexander Pope (‘not convenient’); nor did he approve of the French verse by Pierre-Joseph Bernard (‘not good’).4 All the poets celebrate Sallé’s virtue, although Bernard would later go on to slander Sallé’s name in a privately-circulating verse.5

The bilingual approach to the versification suggests that the dual publication of the engravings in both Paris and London was a plan from the outset. Sallé had performed in London during the 1730-31 theatre season and would return there for the 1733-34 and 1734-35 seasons, so her promotion through this elegant portrait would have been timely. Garnier’s engraving for the fraternal publishers Thomas Bowles II and John Bowles in London is a reverse of the original image.

Both the Paris (de Larmessin) and London (Garnier) engravings were re-purposed. A detail from de Larmessin (the figure of Sallé alone) would become – with the addition of some hand colouring – “Mlle. Sallé règne de Louis XV. d’après Lancret 1730” or plate 58 in an obscure series going by the title “Bureau des modes et costumes historiques.”6 Sallé’s name is still used in the title, although its function is simply to present her costume rather than celebrate her renown as an artiste.

The Garnier engraving also acquired colour in its afterlife as an image simply entitled ‘Dancing’. This was issued by the London-based publisher Robert Wilkinson sometime after he acquired John Bowles’s remaining stock on the latter’s death in 1779.7 Wilkinson evidently had found a niche in publishing images of theatre interiors and exteriors – the digital collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum London includes numerous such images as well as some of the publisher’s theatrical portraits. Wilkinson reissued images of theatre manager John Rich (1692-1761) as Harlequin and of the actor-manager David Garrick (1717-1779) under their own names, but appears to have decided that Sallé’s name would not prove a draw with purchasers over forty years after her final performance at Covent Garden Theatre.

Just as she was retiring from the Paris Opéra, a portrait of Sallé by Jean César Fenoüil was announced in the Mercure of January 1740. The image promotes Sallé as ‘La Terpsicore Françoise’: Terpsichore was the Greek muse of dance, and so this is a most fitting tribute to an acclaimed dancer at the end of her public career. Sallé’s biographer Émile Dacier makes a good case for the writer Titon du Tillet as a likely commissioner of this work.8 Sallé’s persona as a most virtuous woman is indexed in three ways.Verses by Paul Desforges-Maillard conclude by celebrating her expressive capacity as well as her self control: “Love is in her eyes, Virtue in her heart.”

The single turtle-dove in Sallé’s hand can evoke either chastity or love and constancy. The rose in her hair refers to an entrée ‘Les Fleurs’ which she created for Rameau’s opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (Paris Opéra, 1735). Sallé assumed the role of the Rose, queen of the flowers, who collectively endure an assault by the rude north wind Borée but are rescued by the gentle west wind Zéphire. Quite unusually, the action of this dance scene is supplied on the final page of the livret for the opera. Sallé may have wished to draw on the rose’s particular associations with the Virgin Mary — certainly the choice of flower by the painter is a reference to her role in the ‘Ballet des fleurs’ .

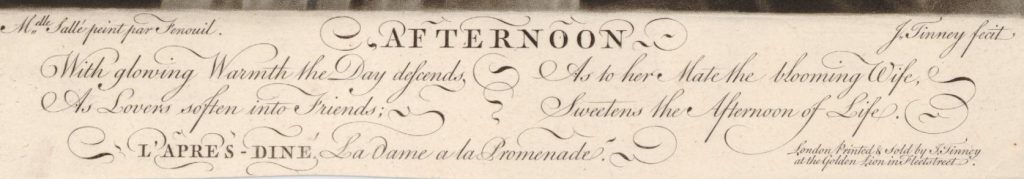

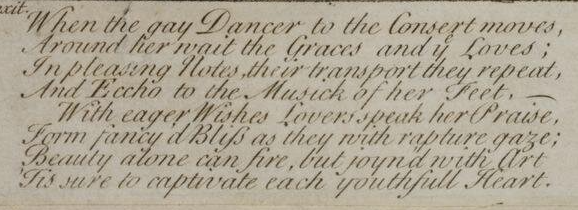

The engraver Petit repurposed this portrait, announcing the new work in the Mercure for July 1742 under the title “L’après-diné – la Dame à la Promenade“. Details such as a hat, necklace and bracelet have been added to the plate, while the attributions of artist and engraver have been retained but changed in format. The original engraving has: “Fenouïl pinxit” and “Petit Sculpt.”; the reissue has: “M.elle Sallé peint par Fenoüil” and “Gravé par Petit”. Before his death in 1761, an enterprising British engraver and seller John Tinney repurposed the image yet again as ‘Afternoon’ in a series of four images depicting the times of day. (According to the British Museum, the remaining three were taken from drawings by François Boucher.) ‘Afternoon’ is accompanied by a fresh poem that reflects its new function depicting a good wife in the afternoon of her life. Tinney retains the credit to the painter and Petit’s second title, while claiming for himself the role of engraver, ‘J. Tinney fecit.’

This re-purposing of images reflected the economic realities of the eighteenth-century print trade: engraved plates represented a considerable investment in time and money, and if they could be made to serve more than one purpose, so much the better. Sallé swiftly lost her celebrity status once she no longer performed at the Paris Opéra, and so the image represented more to its engraver Petit in its new guise. Sallé, although respected in her day as a performer and as a creator of dancers, appears to have lived a modest lifestyle – nor did her circumspect behaviour yield incidents which would render her of sustained interest on a personal level to a broader public.

1) Hall, James. ‘Diana’ in Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art second edition (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008), pp. 105-106 (p. 105). The symbolic interpretations of turtle-dove and rose in this blog are also derived from Hall.

2) For further on Sallé’s reputation see Sarah McCleave, ‘Marie Sallé a Wise Professional Woman of Influence’, Women’s Work: Making Dance in Europe Before 1800 (Studies in Dance History), edited by Lynn Matluck Brooks (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007), pp. 160-182.

3) Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, 14 April 1732 (new style). Lettre 462, Voltaire’s Correspondence, edited by Theodore Besterman (Geneva: Institute et Musée Voltaire, 1953), vol. 2, pp. 299-301.

4) Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, 26 May 1732 (new style). Letter 476, Voltaire’s Correspondence, volume 2, pp. 320-321 (p. 320).

5) Reproduced in McCleave, ‘Marie Sallé’, p. 165.

6) This is the only such plate I have discovered to date.

7) For Robert Wilkinson’s acquisition of Bowles’s stock, see the biographical note on the former at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG51109, accessed 7 December 2022.

8) Émile Dacier, Une danseuse de l’Opéra sous Louis XV. : Mlle Sallé (1707-1756) d’après des documents inédits (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1909), pp. 231-32. For a chatty letter from Sallé to du Tillet dated 27 October 1742, see Dacier pp. 243-247.

‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (Paris: Lancret and de Larmessin, [1732-1735]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

Alexander Pope and John Gay, “I know her now”. Detail from ‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (London: Thos. Bowles and I. Bowles, [1730s?]). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Pierre-Joseph Bernard, “Maitresse de cet Art”. Detail from ‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (London: Thos. Bowles and I. Bowles, [1732-1767]). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

‘Dancing’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret. (London: Robert Wilkinson, [1779-1827]). (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Paul Desforges-Maillard, “Les Sentimens aves les Graces”. Detail from ‘Mlle Marie Sallé La Terpsicore Françoise’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by Gilles-Edme Petit. (Paris: Petit, [1742]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

‘Mlle Marie Sallé La Terpsicore Françoise’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by Gilles-Edme Petit. (Paris: Petit, [1742]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

Anonymous, “With glowing warmth the day descends”. Detail from ‘Afternoon’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by John Tinney. (London: J. Tinney, [1740s-1761]). Copy: British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The next post will consider the Irish dancer Lola Montez (1820-1861).

By Sarah McCleave

Marie Madeleine Guimard (1743-1816) began her professional career as a member of the corps de ballet at the Comédie Française in 1758; within four years she was appointed to the Paris Opéra as danseuse seule en double et figurant. Guimard’s début season for the Opéra saw her assume the role of Terpsichore in Colin de Blamont’s ballet héroïque Les Fêtes grecques et romaines; her rendition of the muse of the dance was subsequently immortalised in Jacques-Louis David’s charming portrait taken in the mid 1770s. In 1766 Guimard – celebrated for her unparalleled grace and refinement as a performer – was promoted to danseuse seule. By the late 1760s she had also become a Parisian celebrity who exerted a particularly strong fascination on her public and the press until she retired in 1789.1 Guimard was highly visible as a talented performer, as an indulged mistress of powerful and well positioned men, as a society hostess, and as a fashion plate –- but also as a philanthropist, patron of the arts and workplace activist. These identities stimulated distinct responses from artists and writers that promoted and prolonged her celebrity status.

Guimard created some of her most noteworthy roles in the 1770s and ’80s. As the young and innocent Nicette in Maximilien Gardel’s La Chercheuse d’Esprit (1778) she avoids an unappealing mercenary match intended by her mother, instead acquiring the youthful and sympathetic Alain as her fiancée. Guimard’s performance impressed Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm with her spirit, delicacy, and natural grace.2 In Gardel’s Le premier navigateur, ou Le pouvoir de l’amour (26 July 1785) Guimard assumed the role of shepherdess Mélide. Newly wed to her beloved shepherd Daphnis, Mélide is separated from him in a great storm, and finds herself on a deserted island. Guimard’s affecting performance of the shepherdess’s utter despair (Act III, sc. 1) is captured in the print featured here. The accompanying verse declares that the virtuous, spirited and generous character of the dancer is united with a grace even more lovely than her beauty.

Elle unit les vertus, l’esprit et la bonté

A la grace plus belle encor que la beauté

Guimard attached herself to men of power and influence; her associations arguably strengthened her position within the Paris Opéra, and demonstrably enabled her to live a life of artistic influence and luxury up until the French revolution. Her artistic liaisons included Hyacinthe, the ballet master of the Paris Opéra’s dance academy; the composer Jean-Benjamin de La Borde, first gentleman in waiting to the King; and the dancer-choreographer Jean Dauberval. Her wealthy supporters included Charles de Rohan, Prince of Soubise and Jarente, Bishop of Orléans. The former’s wealth enabled the dancer to commission a luxurious Hôtel (completed 1770) designed by the King’s architect Claude Nicholas Ledoux. Soubise’s largesse enabled Guimard to establish herself as a society hostess who held thrice-weekly dinners, each for one of three distinct groups: men of influence; the artistic community; and a ‘fast set’ who wanted to indulge in all the sensory pleasures in luxurious surroundings.

A caricature of Guimard as voluptuous hostess to ‘Le Concert à Trois’ would seem to be a comment on her well-funded lifestyle – which typically was supported by more than one lover at a time. The verses attached to the exemplar held by the Institute nationale de l’histoire de l’art (INHA) expand on the charms of each male serenader:

Remarquons ce concert à trois Quel accord! quelle intelligence! Le financier Mondor fier d’en dicter les loix La main sur la pochette en marquer la cadence. L’Officier robuste, au poulmon vigoureux Donne du cor avec beaucoup d’adresse Jeune encore, mais flatté par un succès heureux Le jauvenceau Damis, sur sa flûte s’exerce. Anon., ‘Le Concert à Trois.’ Paris: Martinet, n.d. Institute national d’histoire de l’art (INHA), https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/idurl/1/52364, accessed 24 January 2023.

For those familiar with Guimard’s exploits, the ‘financier’ would be Soubise, the ‘officier robuste’ would be the dancer Dauberval, and the musician likely LaBorde. Guimard’s biographer Edmond de Goncourt – drawing on the Mémoires secrets volume 19 – suggests as much. But he describes a version of the print where the musician (Laborde) is brandishing a conductor’s baton, whereas the INHA exemplar sports a flautist. And the horn player (Dauberval) would in another exemplar (inspected by Goncourt) be replaced with a cleric labelled as the abbé de Jarente.3

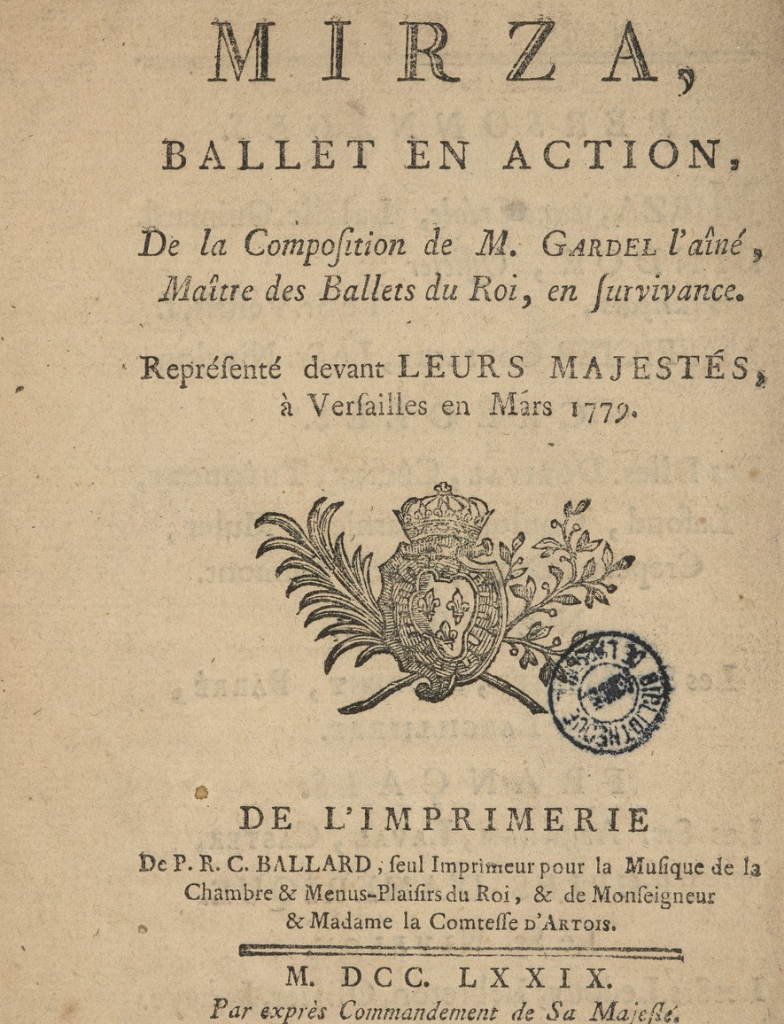

With the addition of these verses (not mentioned in Goncourt) we may have yet another version of this caricature. These can be read in reference to Guimard’s title-role in Gardel’s 1779 ballet Mirza, where she plays the daughter of a south-sea island’s Governor, going by the name of Mondor. (Mondor was played by Dauberval.) The French military – in which Mirza’s husband Lindor serves as an officer –

must quell an uprising of the native ‘savages’; the intercession of the wife of their chief (Mlle Heinel) saves Mirza, who in turn implores her father for clemency, thus saving the life of the ‘savages’’ chief. In the fourth act there is a festival that opens with cannon shot accompanied by military instruments, followed by a ‘Symphonie à grand Orchestre’. Mondor conducts a party of the French dignitaries to a banquet, in which a chorus celebrates the beauty and grace of Mirza, as well as her capacity to cultivate l’amitié.

And yet the names of the male figures in the caricature’s verses map even more closely onto a one-act comedy, Le Faux-Seing, ou l’Adroitte Soubrette, written by Agricol Lapierre-Châteauneuf and performed in Marseille, Avignon, and other locales in 1787. This publication of its text was announced in the Journal des théâtres for 28 January 1795. Lisette (the adroit soubrette) is trying to counsel the youthful and timid Damis in his suit of Lucile, who risks being affianced to the rich Mondor at the desire of her mother. Mondor dismisses the suit of his young rival in front of Lucile; the situation escalates until epées are nearly drawn and Lucile is obliged to separate the men. Damis cedes to Mondor. Lucile – who does not wish to marry Mondor under any circumstances – makes her mother promise not to force a choice of spouse on her. Lucile’s mother tells Mondor she will not oblige the marriage; he produces gold in the firm hope that financial inducement will grant his wishes.

The glasses worn by the Mondor character in the caricature are key to the next scene, in which due to the inadequacy of his lunettes he has Lisette write a letter to Lucile at his dictation, declaring his love and offering her his worldly goods. Lisette even signs the letter, putting the name of ‘Damis’ to it. Damis disavows the missive but is sufficiently emboldened to kiss Lucile’s hand. The piece ends with Mme Lisimon uniting the lovers and Mondor retiring in indignation. The critic reviewing the publication notes the similarity with this work’s Mondor and a character of the same name in Fausses Infidélitiés; Damis was likely inspired by le Timide, a comedy written by Paschali that was performed at the theatre of the Variétés (renamed the theatre of the Republique) six or seven years previous.4

Guimard was not directly connected with any of these works (apart from Mirza), but they add a context in which this caricature could have been understood by her contemporaries – who may have been tempted to compare her lovers with popular fictional characters. The penciled identification of ‘Mlle Guimard’ as the subject implies that at least one viewer readily associated the dancer with a situation where a voluptuous and well-off woman appears to be courted by three different men – each having different attributes to recommend them. Since 1789, Guimard had been married to the musician-dancer-writer

Jean-Étienne Despréaux, who may be represented by the ‘young still, flattered by a happy success’ flautist Damis in this print. Despréaux – some 15 years Guimard’s junior – would prove a congenial companion for her retirement years, notwithstanding that the couple would lose their court-established pensions and lived in very straightened circumstances during their final years together.

Although cast in ‘Le Concert à Trois’ as a good time girl relishing her life of luxury, Guimard was also known for her generous spirit and her capacity to use her good fortune to help others. March 1768 had seen a remarkable frost in Paris that brought attendant suffering with it. Guimard extracted 6000 francs from her lover Soubise (in lieu of an expected present of jewellery), added 2000 francs of her own money, and used these funds to distribute – in person – food and other necessities to the poor of her parish.3 This act of charity by a celebrated artiste from the Paris Opéra was the subject of a flattering caricature ‘Terpsicore charitable ou mademoiselle Guimard visitant les pauvres’ by an unknown contemporary. While we could dismiss this effort as a publicity stunt, Guimard’s actions at other junctures in her life display a genuine philanthropic spirit.

For example, she was a noted benefactor of artists. At the most direct level Guimard commissioned art work – such as the bust sculpture of herself by Gaetano Merchi (1747-1823) rendered in 1779. Her support of the young painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) extended to supporting his study abroad; this relationship remained of sufficient interest to become a featured illustration for the 1894 Christmas edition of L’Illustration.

Guimard – whose celebrity was largely extinguished by the turbulent events and the harsh values of the Revolution – again became a subject of reprinted images and magazine features from the mid nineteenth century. In a cultural milieu where the history of dance was a matter of interest, she regained some visibility due to her iconic status as the leading female dancer of her generation.

‘Marie Madeleine Guimard.’ 1840. Eugène Gervais after François Boucher. [Paris]: F. Chardon aîné. Source: BnF/Gallica. Accessed 24 January 2023.

‘Terpsichore charitable.’ 1780. A Paris, chez M. Delaporte, cour du Commerce, rue des Cordeliers. Source: BnF/Gallica. Accessed 13 Dec. 2022. No artists are identified, either on the print or in the catalogue record.

‘Mlle Guimard dan le ballet du Navigateur.’ [1787]. Jean-François Janinet after André Dutertre. [Paris]. Source: New York Public Library. Accessed 29 January 2023.

‘David chez la Guimard.’ 1894. L’Illustration Numéro de Noël, Décembre, p. 9.

The next post will consider the dancer-choreographer Marie Sallé (1709-1756).

By Sarah McCleave

Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo (1710-1770) is acclaimed as a female dancer who took on the most challenging aspects of contemporary dance technique, displaying a capacity to render jumps, entrechats (jumps with crossed feet), turns and beaten steps at a level normally confined to her male peers. Initially trained by her father in her native city of Brussels, the support of the Princesse de Ligne took Camargo to Paris where she studied under the famous Françoise Prévost. Father and daughter assumed a joint appointment at the theatre in Rouen before returning to the Paris Opéra in 1726 where Marie-Anne enjoyed a glittering career spanning 25 years – interrupted by a six-year sabbatical (1734/5-1740) at the behest of her then lover Louis de Bourbon, Comte de Clermont. Camargo rounded off her career with engagements at each of London’s patent theatres, dancing at Drury Lane theatre during the 1750-51 season and at Covent Garden theatre for the following two seasons.

It would be easy to fill several blogs with tales from Camargo’s colourful private life, but this would be to overshadow her considerable professional achievements.1 Of the anecdotes surrounding her, that of an early triumph at the Paris Opéra is worth repeating because it encapsulates the traits for which she became famed as a performer. The event occurred when she was a young dancer, and had been relegated to the corps de ballet notwithstanding a highly successful début on 5 May 1726. Camargo saw an opportunity when David Dumoulin missed his entry for a solo as a demon. According to the musicologist and critic François-Henri-Joseph Blaze (1784-1857):