Marie Sallé (1709-1756) was an acclaimed French dancer who performed and created dances in venues as disparate as the Parisian foires, the patent theatres of London, and the Paris Opéra. She was the subject of a few portraits, two of which are of interest for the ways in which they were re-purposed after her retirement as a performer.

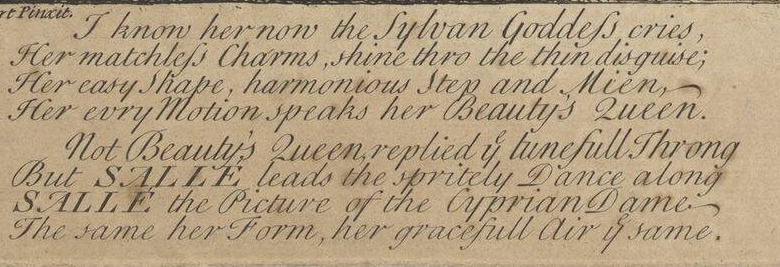

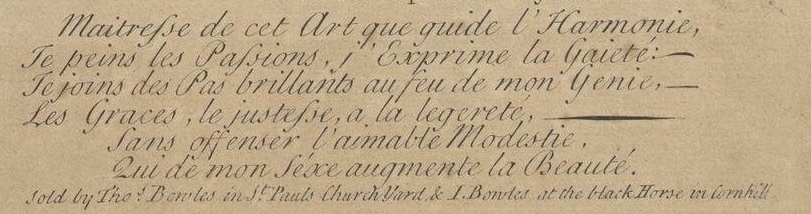

In 1732, after Sallé had reached the status of principal dancer at the Paris Opéra, her portrait was drawn by the fashionable artist Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). The Sallé painting was engraved and published by Nicolas de Larmessin (1684-1755), at that time the French royal family’s official portraitist. Lancret places Sallé within a ‘genre scene’ rather than producing a traditional portrait. Sallé, holding an attitude with great elegance, is in an outdoor setting that includes a temple of Diana on one side and a bevy of accompanying dancers on the other. Why the temple of Diana? According to James Hall, ‘the stern and athletic personification of chastity, is only one aspect of a many-sided deity’,1 but it is most probably the aspect being evoked here. Lancret’s subject is not a reference to any known role of Sallé’s, but rather promotes her carefully cultivated personal reputation.2 Voltaire – who supported Sallé by writing letters of introduction for her during the early years of his own career – wrote about this portrait in his correspondence to the writer Nicolas-Claude Thieriot during April-May of 1732. Voltaire saw the portrait in Lancret’s studio,3 and expressed a general dissatisfaction with the English verse attached to it by John Gay and Alexander Pope (‘not convenient’); nor did he approve of the French verse by Pierre-Joseph Bernard (‘not good’).4 All the poets celebrate Sallé’s virtue, although Bernard would later go on to slander Sallé’s name in a privately-circulating verse.5

The bilingual approach to the versification suggests that the dual publication of the engravings in both Paris and London was a plan from the outset. Sallé had performed in London during the 1730-31 theatre season and would return there for the 1733-34 and 1734-35 seasons, so her promotion through this elegant portrait would have been timely. Garnier’s engraving for the fraternal publishers Thomas Bowles II and John Bowles in London is a reverse of the original image.

Both the Paris (de Larmessin) and London (Garnier) engravings were re-purposed. A detail from de Larmessin (the figure of Sallé alone) would become – with the addition of some hand colouring – “Mlle. Sallé règne de Louis XV. d’après Lancret 1730” or plate 58 in an obscure series going by the title “Bureau des modes et costumes historiques.”6 Sallé’s name is still used in the title, although its function is simply to present her costume rather than celebrate her renown as an artiste.

The Garnier engraving also acquired colour in its afterlife as an image simply entitled ‘Dancing’. This was issued by the London-based publisher Robert Wilkinson sometime after he acquired John Bowles’s remaining stock on the latter’s death in 1779.7 Wilkinson evidently had found a niche in publishing images of theatre interiors and exteriors – the digital collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum London includes numerous such images as well as some of the publisher’s theatrical portraits. Wilkinson reissued images of theatre manager John Rich (1692-1761) as Harlequin and of the actor-manager David Garrick (1717-1779) under their own names, but appears to have decided that Sallé’s name would not prove a draw with purchasers over forty years after her final performance at Covent Garden Theatre.

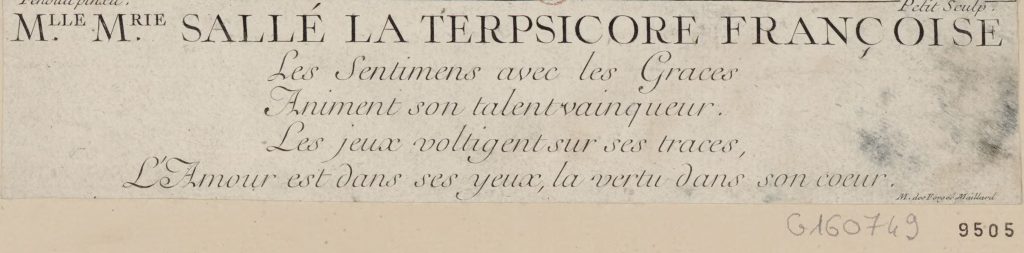

Just as she was retiring from the Paris Opéra, a portrait of Sallé by Jean César Fenoüil was announced in the Mercure of January 1740. The image promotes Sallé as ‘La Terpsicore Françoise’: Terpsichore was the Greek muse of dance, and so this is a most fitting tribute to an acclaimed dancer at the end of her public career. Sallé’s biographer Émile Dacier makes a good case for the writer Titon du Tillet as a likely commissioner of this work.8 Sallé’s persona as a most virtuous woman is indexed in three ways.Verses by Paul Desforges-Maillard conclude by celebrating her expressive capacity as well as her self control: “Love is in her eyes, Virtue in her heart.”

The single turtle-dove in Sallé’s hand can evoke either chastity or love and constancy. The rose in her hair refers to an entrée ‘Les Fleurs’ which she created for Rameau’s opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (Paris Opéra, 1735). Sallé assumed the role of the Rose, queen of the flowers, who collectively endure an assault by the rude north wind Borée but are rescued by the gentle west wind Zéphire. Quite unusually, the action of this dance scene is supplied on the final page of the livret for the opera. Sallé may have wished to draw on the rose’s particular associations with the Virgin Mary — certainly the choice of flower by the painter is a reference to her role in the ‘Ballet des fleurs’ .

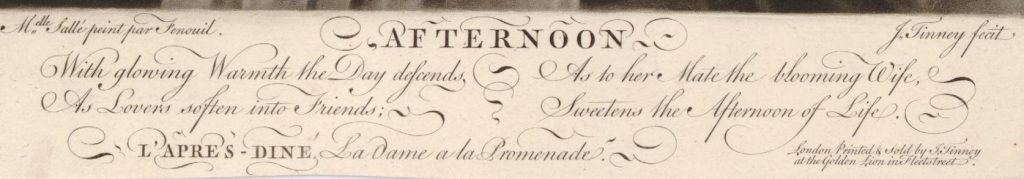

The engraver Petit repurposed this portrait, announcing the new work in the Mercure for July 1742 under the title “L’après-diné – la Dame à la Promenade“. Details such as a hat, necklace and bracelet have been added to the plate, while the attributions of artist and engraver have been retained but changed in format. The original engraving has: “Fenouïl pinxit” and “Petit Sculpt.”; the reissue has: “M.elle Sallé peint par Fenoüil” and “Gravé par Petit”. Before his death in 1761, an enterprising British engraver and seller John Tinney repurposed the image yet again as ‘Afternoon’ in a series of four images depicting the times of day. (According to the British Museum, the remaining three were taken from drawings by François Boucher.) ‘Afternoon’ is accompanied by a fresh poem that reflects its new function depicting a good wife in the afternoon of her life. Tinney retains the credit to the painter and Petit’s second title, while claiming for himself the role of engraver, ‘J. Tinney fecit.’

This re-purposing of images reflected the economic realities of the eighteenth-century print trade: engraved plates represented a considerable investment in time and money, and if they could be made to serve more than one purpose, so much the better. Sallé swiftly lost her celebrity status once she no longer performed at the Paris Opéra, and so the image represented more to its engraver Petit in its new guise. Sallé, although respected in her day as a performer and as a creator of dancers, appears to have lived a modest lifestyle – nor did her circumspect behaviour yield incidents which would render her of sustained interest on a personal level to a broader public.

References

1) Hall, James. ‘Diana’ in Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art second edition (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008), pp. 105-106 (p. 105). The symbolic interpretations of turtle-dove and rose in this blog are also derived from Hall.

2) For further on Sallé’s reputation see Sarah McCleave, ‘Marie Sallé a Wise Professional Woman of Influence’, Women’s Work: Making Dance in Europe Before 1800 (Studies in Dance History), edited by Lynn Matluck Brooks (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007), pp. 160-182.

3) Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, 14 April 1732 (new style). Lettre 462, Voltaire’s Correspondence, edited by Theodore Besterman (Geneva: Institute et Musée Voltaire, 1953), vol. 2, pp. 299-301.

4) Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, 26 May 1732 (new style). Letter 476, Voltaire’s Correspondence, volume 2, pp. 320-321 (p. 320).

5) Reproduced in McCleave, ‘Marie Sallé’, p. 165.

6) This is the only such plate I have discovered to date.

7) For Robert Wilkinson’s acquisition of Bowles’s stock, see the biographical note on the former at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG51109, accessed 7 December 2022.

8) Émile Dacier, Une danseuse de l’Opéra sous Louis XV. : Mlle Sallé (1707-1756) d’après des documents inédits (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1909), pp. 231-32. For a chatty letter from Sallé to du Tillet dated 27 October 1742, see Dacier pp. 243-247.

Images

‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (Paris: Lancret and de Larmessin, [1732-1735]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

Alexander Pope and John Gay, “I know her now”. Detail from ‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (London: Thos. Bowles and I. Bowles, [1730s?]). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Pierre-Joseph Bernard, “Maitresse de cet Art”. Detail from ‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (London: Thos. Bowles and I. Bowles, [1732-1767]). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

‘Dancing’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret. (London: Robert Wilkinson, [1779-1827]). (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Paul Desforges-Maillard, “Les Sentimens aves les Graces”. Detail from ‘Mlle Marie Sallé La Terpsicore Françoise’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by Gilles-Edme Petit. (Paris: Petit, [1742]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

‘Mlle Marie Sallé La Terpsicore Françoise’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by Gilles-Edme Petit. (Paris: Petit, [1742]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

Anonymous, “With glowing warmth the day descends”. Detail from ‘Afternoon’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by John Tinney. (London: J. Tinney, [1740s-1761]). Copy: British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Next post

The next post will consider the Irish dancer Lola Montez (1820-1861).