OLIVE BALDWIN & THELMA WILSON

Image 1) ‘Nancy Dawson’, her hornpipe. From The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/49d8b010-3448-0131-1b38-58d385a7b928

Nancy Dawson had a seven-year career, dancing on the London stage from 1756 to 1763. She became a celebrity overnight in October 1759, when Covent Garden’s dancer Francis Miles fell ill and she replaced him as the performer of the hornpipe in the Newgate scene of the prisoners in chains in The Beggar’s Opera (1). Her popularity attracted the immediate attention of gutter journalists and print sellers. Dawson’s only speciality on stage was her hornpipe, so it is perhaps surprising to find that this dancer, with a short career and limited range, appeared in the 1888 edition of the Dictionary of National Biography, where she is described as ‘of shrewish temper, heartless and mercenary, and of notoriously immoral life’ (2). Moreover, between 1860 and 1958 she figured over thirty times in Notes and Queries, with various respectable contributors showing a strong interest in the more lurid aspects of her reputation, much of which seems to have been acquired long after her death.

Two very similar anonymous celebrity ‘biographies’ quickly appeared, The Genuine Memoirs of the Celebrated Miss Nancy D―n (London: R. Stevens, 1760) and The Authentic Memoirs of Celebrated Miss Nancy D*w*n (London: Tom Dawson, [1762?]) (3). A review of The Genuine Memoirs in the London Magazine; or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer of October 1760 dismissed the publication as ‘ridiculous, yet pernicious’ (p. 560), and indeed, like other catchpenny ‘memoirs’ of the time, it consists of a good deal of scurrilous invention. However, her supposed low-life origins and amours were generally accepted as fact until the editors of the Biographical Dictionary of Actors consulted Dawson’s will. Her father, William Newton, was not a pimp and porter, nor had her drunken mother died in a gutter, for he ran a stay-making business in the Covent Garden area and Nancy left suitable bequests to her father and to his wife, her ‘dear mother’.

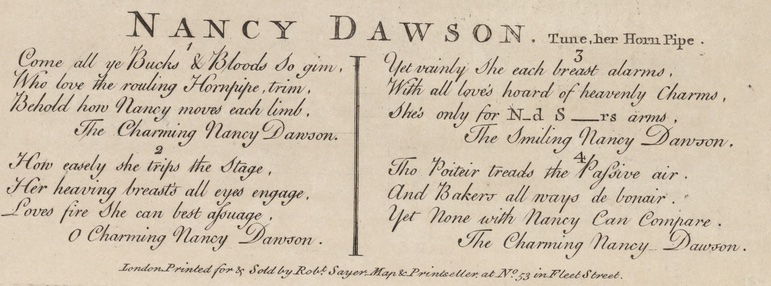

Prints of Nancy Dawson were rapidly produced. The Genuine Memoirs included a crudely executed frontispiece showing her dancing among the thieves in The Beggar’s Opera and prints for sale in the shops quickly followed. There were essentially two different images, one showing her about to begin her stage hornpipe (see Image 1, above) and one that is clearly based on Reynolds’s portrait of the courtesan Kitty Fisher (see Images 2-3, below). In both, she is wearing the straw hat that was part of her hornpipe costume. In time, assumptions as to her character came to be drawn from these prints. In February 1866 a correspondent to Notes and Queries described the image showing her about to dance on stage as depicting ‘a young lady of saucy appearance … in the act, apparently, of asking someone to walk in’, while in 2012 Kevin Bourque, in Blind Items: Anonymity, Notoriety, and the Making of Eighteenth-Century Celebrity assumed that the use of the image of Kitty Fisher showed that Nancy Dawson, too, was a notorious courtesan, rather than seeing it as a way of quickly and cheaply producing a print of a stage celebrity (4).

Kitty Fisher (Image 2, above) by Joshua Reynolds.

Nancy Dawson (Image 3, below) by Charles Spooner.

Three years before her first advertised stage appearance Ann [Nancy] Newton married James Dawson, a mariner, who seems to have soon disappeared from her life (5). The scandal associated with her in her lifetime arose from her affair with the popular comic actor Edward Shuter, which was repeatedly referred to in song lyrics and satires. The catchy tune to which she danced her hornpipe was named after her and verses in her honour were fitted to it, beginning ‘Of all the girls in our town … There’s none like Nancy Dawson’. Here ‘Shuter droll’ is represented as standing in the way of other lovers, while another set of verses (‘Come all ye bucks and bloods so grim’ — see Image 4, below) states ‘She’s only for N―d S―r’s arms / The smiling Nancy Dawson’. In 1763 G. A. Stevens, who had quarreled with Shuter, wrote a tedious general satire entitled The Dramatic History of Master Edward, Miss Ann, and Others, in which Nancy does not appear until page 137. The couple are shown quarreling and coming to blows, and this section of Stevens’s satire seems to have been responsible for the description of her character in the Dictionary of National Biography entry as shrewish and mercenary. The relationship between Nancy Dawson [Dawsonia] and Ned Shuter [Shuterius] also features in the anonymous satire The Battle of the Players (London: W. Flexney, 1762).

Image 4 ‘Nancy Dawson’, her hornpipe, detail from Image 1.

Nancy worked with Shuter from autumn 1757, when she joined the Covent Garden company (6), and it is likely that they were still lovers when they appeared in Dublin together in summer 1763, a few months before she left the stage. Her will was made in May 1767, a month before her death, and the Biographical Dictionary of Actors (BDA) states that she left Shuter a mourning ring but did not notice that she also left him ‘all my Money in the publick Funds belonging to the Glass Cases in both my parlours’ and asked for him to be one of the pall bearers at her funeral (7). She may, of course, have had other lovers but no names survive. Nancy Dawson seems to have kept her friends, for at her last benefit she danced a double hornpipe with John Walker, the Drury Lane dancer and dancing master who taught her the hornpipe (8). She asked for Walker to be a pall bearer and left mourning rings to him and his dancer wife.

To be continued.

Notes

1. For a full account of Nancy Dawson’s life and reputation, see Olive Baldwin and Thelma Wilson, ‘Nancy Dawson, her hornpipe and her posthumous reputation’, Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Theatre Research, 30.1-2 (2015), 55-71.

2. S.v. ‘Dawson, Nancy’ by A.V. [Alsager Richard Vian], in Dictionary of National Biography, edited by Leslie Stephen, 63 vols. (London: Smith, 1885-1900), vol. 14.

3. The Life of Lavinia Beswick, alias Fenton, alias Polly Peachum (London: A. Moore, 1728) is a similarly unreliable work about Lavinia Fenton, the first Polly in The Beggar’s Opera.

4. Kevin J. Borque, Blind Items: Anonymity, Notoriety, and the Making of Eighteenth-Century Celebrity, Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin (2012); Nancy Dawson was also paired with Kitty Fisher in Whore Biographies, vol.4, edited by Julie Peakman (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2006).

5. The marriage took place on 1 January 1753 (National Archives, Kew, Marriage records of the Fleet).

6. Will of Ann Dawson of Saint George the Martyr , Middlesex, 24 May 1767, PROB 11/929/346, National Archives, Kew.

7. I.C.B. Dear, and Peter Kemp, The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 376.

8. Nancy Dawson’s Cabinet of Choice Songs, being a collection of some of the most superlative, amatory, flash, luxurious, and dainty ditties, ever before printed (London: W. West, [1842?]). In the British Library catalogue, the author of the collection (C.116.a.45) is given as Nancy Dawson!

Images

- Anonymous. ‘Nancy Dawson’, her hornpipe. London: Robert Sayer, [c.1762]. Engraving. From The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/49d8b010-3448-0131-1b38-58d385a7b928. Accessed 24 August 2021. Public domain.

- Joshua Reynolds. ‘Miss Kitty Fisher.’ London: Robert Sayer, 1763. Mezzotint. London: Robert Sayer, [c. 1760]. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

- Charles Spooner. ‘Nancy Dawson.’ London: Robert Sayer, [c.1763]. Mezzotint. From The New York Public Library, https://nypl.getarchive.net/media/nancy-dawson-43e358. Accessed 24 August 2021. Public domain.

- Detail from Image 1, above.

Next post

‘The reputation of Nancy Dawson part 2’ will appear on 10 September 2021.