By Sarah McCleave

Lola’s determination to try her luck in America demonstrated her capacity to take on new challenges and her quest for adventure. In her initial four-year sojourn to that country (1851-1855), she traversed a goodly span of the still-expanding United States, developing her skills as an actress and a lecturer while still remaining active as a ‘Spanish dancer’. This blog will focus on the kind of reception she attracted, particularly in the print media.1) Lola had already been an occasional subject of interest in the American press since her London début, where her persona as a “Spanish danseuse who has created a great sensation” was lauded for demonstrating a “bewitching” softness and suppleness (Daily Evening Transcript, Boston, 29 July 1843). Symptomatic of her status as a celebrity, Lola received more intense coverage during her turbulent period in Munich. Philadelphia’s Public Ledger offered a terse account of the Munich riots that served mainly to apportion blame:

Lola Montez the dancer, by her impudent conduct and unpopularity, has occasioned a riot at Munich which compelled her to leave.2

Public Ledger (Philadelphia), 20 March 1848

Lola’s peregrinations since fleeing Munich eventually led her to Paris by late March 1851. She subsequently prepared her return to the stage, placing herself under the tutelage of dancer turned impresario Charles Mabille, who choreographed a tarentella as well as Bavarian, Hungarian, and Tyrolean dances for her. She made important contacts with Americans such as Edward Payson Willis, younger brother of the editor and author Nathanial Parker Willis; Lola also intrigued James Gordon Bennett, editor and publisher of the New York Herald – who would lead his peers in providing Montez with what amounted to free publicity throughout her American period. The younger Willis had encouraged Lola to make an American tour; she duly made provision for this when, on 26 August 1851, she signed a six-month contract with the Parisian-based agents Roux et cie (later reneged in favour of Payson Willis). On 12 September Lola offered a private preview of her repertory at the Jardin Mabille, before undertaking what would be her final European tour through parts of France, Belgium, and what is now Germany.3)

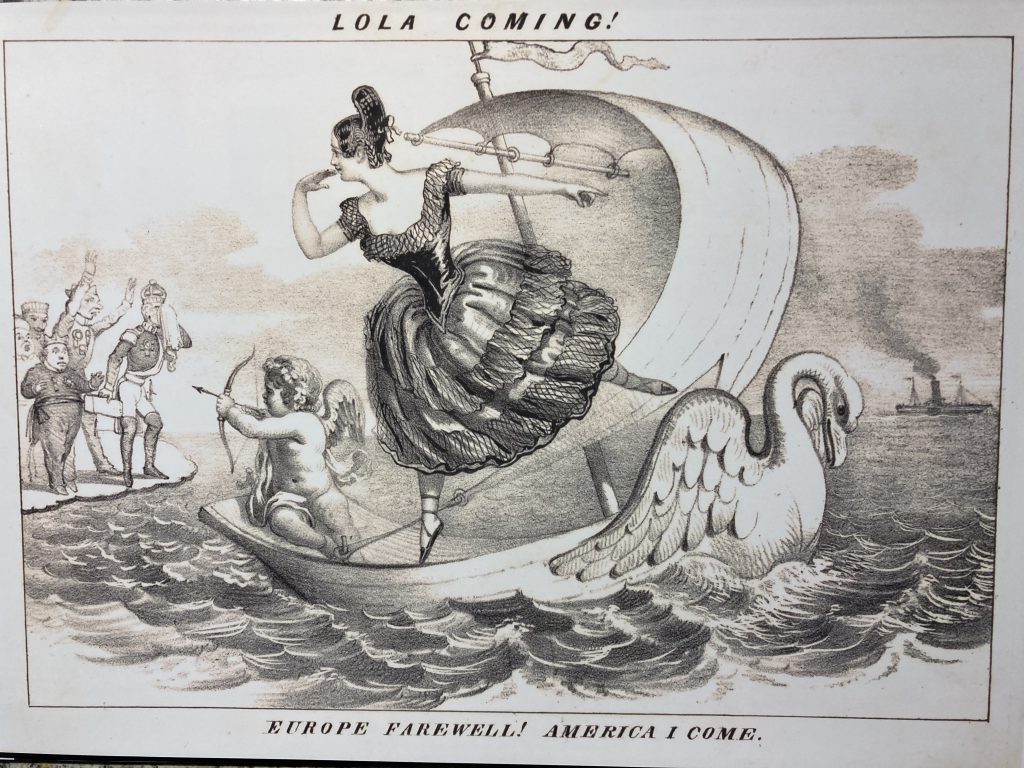

Lola’s arrival Stateside was already anticipated. On 22 August 1851, the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel and Gazette dismissed her as a “notorious courtesan concerning whose probable visit to this country much has been said of late”. By the time Lola had disembarked the Humboldt in New York city on 5 December 1851, her arrival had also attracted the attentions of thespian-turned-caricaturist David Claypoole Johnston (1798-1865). Johnston was inspired to comment on Lola’s capacity to disrupt and to stimulate through a pair of images: directly below we have ‘Lola coming!’ which depicts a pert dancer aloft a departing boat, cheerily saluting a group of variously stunned or bereft men of high station, including an openly distraught king Ludwig (presumably the weeping figure with handkerchief).

Johnstone also marked Lola’s arrival with ‘Lola is come!’ (see featured image, above). News editor Bennett takes pride of place to our right, in what would have been the best seat in the house for enjoying Lola’s “bewitching” postures up close — and for determining whether she sported knickers or not. We have an anonymous puritan in the audience, showing both disapproval (through the tract in his hand) and fascination (the expanded iris of his one visible eye as he stares through his fingers at the audacious dancer). It is not known whether the stage manager to the left – keenly anticipating his acquisition of 50% of the proceeds – is Broadway Theatre manager Thomas Barry (at whose theatre Lola made her American début on 29 December 1851) or merely a figure representative of his profession.4)

Lola’s performances attracted both advance notices and reviews in the press. Of the latter, one of the more favourable notices lauded her “great ability” in the pantomime sections of the ballet, Betley the Tyrolean, claiming Montez the equal to the “versatile and expressive mime artist” Céline Céleste. (Céleste had toured the US on several occasions, most recently in 1851.) 5) Montez’s dancing made an impression as “decidedly unique and original”; her acting displayed a capacity to make an ungratefully-written character appear interesting although her voice lacked projection in its upper range. As to her person, Montez of the “remarkably beautiful” eyes also possessed a “good” figure, “incomparably graceful” action and a “most radiant” smile. (The Mississippi Free Trader, 26 January 1853). On 19 January 1851 , the same paper had already reported on Lola graciously sharing the tributes and bouquets of an enthusiastic audience with her colleagues; this action endeared her to the audience still further.

Tonight she will perform a pas seul … [she] will be original. She copies from no one; she is herself alone.

Mississippi Free Trader (Natchez), 19 January 1853, p. 2

Whether Lola’s authenticity as a performer was mirrored in her off-stage persona is debatable. The generosity she displayed on the Natchez stage may have been calculated to stimulate positive publicity, but if so was certainly not a one-off: the “much beloved” Lola had been reported offering “unbounded” acts of charity to the poor whilst resident on Lake Geneva in 1848; in 1852, she offered a charitable performance for the Disabled firemen at Philadelphia’s Walnut theatre. For the latter act she was rewarded with a formal presentation that was duly recorded in the press.6) And while her regrettable temper underpinned her most audacious actions – including her tendency to brandish whips, pistols, or poison when editors or theatre managers treated her unfavorably 7) – she also demonstrated genuine courage, as this anecdote regarding an encounter with a group of army officers reveals:

Lola Montez is bound to keep herself before the public. It is related that while she was in Montreal she visited a well-known confectionary establishment on Notre-Dame street, and while there was annoyed by the entrance of several young army officers, who, under the pretence of buying something, gazed pertinaciously and unpleasantly at her. After submitting awhile, Lola walked up to the mistress of the saloon and asked, “Madam, how much do these persons owe you?” Her only answer at first was a look of surprise, but on the question being repeated, she was told “One shilling and sixpence.” “Here it is, then,” said Lola, “I would not wish that these gentlemen should lose a single copper in gratifying their curiosity by staring at me.” The officers retreated in confusion.

Lowell Daily Citizen and News (Lowell, Massachusetts), 22 October 1857, p. 1

This tale also shows Montez harnessing her capacity to be unconventional to good effect: the socially aggressive officers could not have anticipated her response, nor could they find any answer to it apart from retreat. Within weeks of her arrival, a Milwaukee-based journal offered the following evaluation of Montez’s character:

She is daring, reckless, if you will, and is unwilling to be bound down by the ordinary rules of the social compact. If a gentleman should insult her, she would shoot him, and not expect any one to do it for her.

Wisconsin Free Democrat, 21 January 1852

After four years supporting herself while cultivating her celebrity status in the United States, on 6 June 1855 Lola left her final residence in San Francisco for pastures new — boarding the Fanny Major bound for Sydney.

References

- For a most engaging use of press reports to forge a narrative of Lola’s American years, see Bruce Seymour, Lola Montez a Life (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), pp. 283-330. This blog has also conducted an independent investigation of America’s Historical Newspapers (Readex). All newspaper references in this blog are taken from this subscription resource.

- The Philadelphia Ledger returned to the subject of Lola whenever she became associated with violent scandal: see the article ‘Lola Montez and the Jesuits’ (3 May 1852) that reports on the forcible ejection of an Italian count from her suite at the Howard Hotel; the incident culminated in a pitched row between two groups of men that the paper was happy to report on while painting Lola as a vengeful harpy.

- These events are detailed in Seymour, pp. 268-279. While Seymour’s index tentatively attributes the poet Victor Mabille as Montez’s coach and choreographer, it seems far more likely that the dancer Charles Mabille (1816-1858) assumed this role.

- It is not possible to identify with confidence Lola’s contact from among several roughly contemporaneous actors known as Thomas Barry. The Irish actor-manager Thomas Barry (1743-1768) was born too late; Thomas Barry Sullivan (1821-1891) was not based in the US at the correct time. It is not known whether the Thomas Barry managing New York’s Broadway theatre in 1851 also managed a Boston theatre in 1856, see https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/8131256.

- For the review of Montez see Daily Evening Transcript (Boston), 18 March 1852. For the evaluation of Céline Céleste and her American dates, see J. Moody, 2006, Céleste [married name Céleste-Elliott], Céline [known as Madame Céleste] (1810/11–1882), actress and theatre manager. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 25 May 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/4987.

- For Lola’s actions in Lake Geneva, see the Daily Evening Transcript (Boston), 1 August 1848; for the Philadelphia episode, see the Public Ledger (Philadelphia), 2 February 1852.

- For two of her challenges to men of the press, see the Albany Evening Journal, 18 August 1853 and 16 December 1854; for a charge of assault and battery raised in regards to the manager of the Varieties theatre, see the Mississippi free Trader of 26 April 1853.

Next post

The next post will consider Lola Montez’s reception in Australia.