And then we’re all objects – the living and the dead. There’s no difference.

(95)

As she kneels over Kenji’s dead body, preparing to chop it up, Yoshie summarises for readers one of the central tenets of Natsuo Kirino’s disturbing Out, which is a plot driven by the author’s investigation and critique of life in modern Japan. In this novel, bodies are nothing more than an economic transaction in the world of baccarat clubs, bento-box factories and the bathrooms of your colleague’s house, where you can get your husband chopped up with a sashimi knife for a price.

Kirino truly succeeds in illustrating the dire conditions endured by her protagonists and using them as a vehicle to portray the soul-destroying effects of labour in contemporary Japan, and I see this largely being achieved by her complete (and literal) detachment of bodies from their autonomy and transforming them into something a little more “businesslike” (97).

(Natsuo Kirino for Makoto Watanabe)

The concept of ‘the body’ in the novel is so far removed from the humane that it is possible in Kirino’s imagining of the Tokyo suburbs that anybody can literally be belittled and reduced to nothing more than any other body, some mutilated flesh in a shopping bag in exchange for some 500,000 yen.

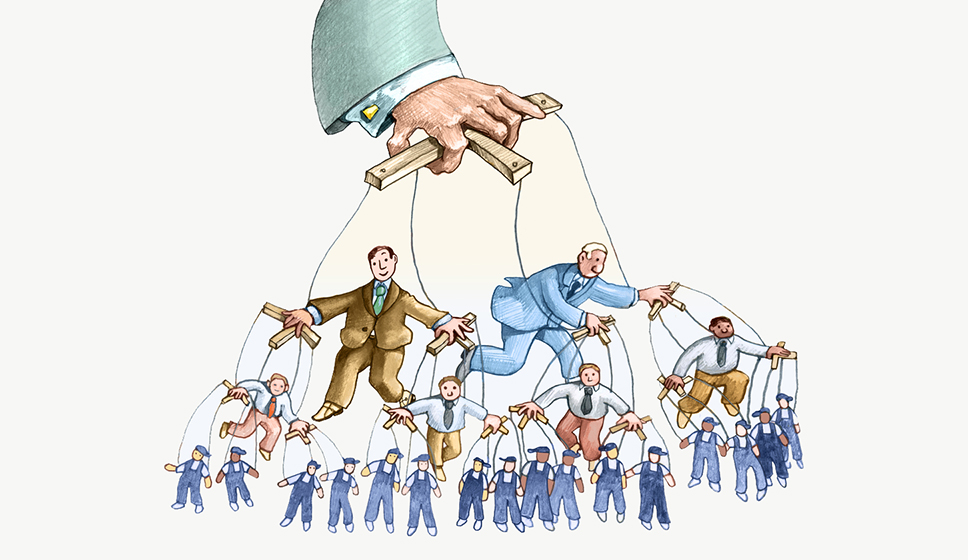

The transactions of bodies we see in this text reflect and critique the role they perform as a cog in the wheel of human capitalism in the industrial world of Japan. While reading this text, I felt Michel Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and biopower taking centre stage in how the Japanese culture of industry is illustrated as being powerful and having a central role in the lives and the survival of our characters. These characters work in dire conditions that see them “standing on the cold concrete floor” (Kirino 11) for hours at a time, with “a replacement filling in on the line” as they run for bathroom breaks. The characters are portrayed as having accepted this as their reality and have assumed a rather docile position in the workplace.

This was the secret to lasting at a place like this without ruining your health.

11

It seems that the factory views its staff as a body of work that makes up one labour force, working as a “team” (Kirino 11) to achieve mass production for low costs. This level of control is reminiscent of what Foucault said in one of his lectures at the Collège de France, that “a … seizure of power … is directed not at man-as-body but at man-as-species … a “biopolitics” of the human race” (Society Must Be Defended 243). Seeing the workers as nothing more than a “species” reduces them to little more than one singular body made valuable through the volume of production that it can achieve.

There’s a transaction at play here: the workers surrender their dignity and their humanity to the machine in exchange for low pay and, arguably, escape from their depressing home lives. The machine, in turn, exploits their ‘humanness’ and, with that, their capabilities to function as one large workforce in order to achieve maximum production.

Ben Anderson’s idea of “the ‘object-target’” (‘Affect and Biopower’ 28) is an interesting lens for this text and looking at how the central characters of Out pertain to and adhere to this definition uniquely because of their marginality, highlights the formative role they play in the “contemporary forms of biopower” (29) in industrial Japan. Readers are made starkly aware of how easily reduced human beings can be to a mass of life that is quantified and used as a resource for the state. Human life, as we see it in Out, has “become the ‘object-target’ for specific techniques and technologies of power” (Anderson 28).

In his observation here, Anderson is referring to the concept of biopower, which is slippery in its frustratingly variable definition but broadly translates to the power over life. I find it really intriguing how Kirino’s depiction of biopower and biopolitics does not give a blanket illustration of this control over Japanese lives. Rather, she offers nuanced insights into how biopower is engaged with very marginalised groups like the Brazilian-Japanese population and the four women that are the focal point of the plot.

… if your husband is white-collar, the wife is blue …

New york times

In an interview with the New York Times, Kirino remarks on how the status of the woman in Japanese society “inevitably remains a rung below” (French, “A Tokyo Novelist Mixes Felonies with Feminism”). It is interesting how Kirino’s writing asks readers to look between the lines here and see how industry in Japan takes advantage of these groups of people who are unable to upskill and are given no alternative but to work in unskilled labour. I believe this is why Masako seems to be given a central role in the novel as Kirino has noted that Masako “is a symbol of Japanese women who cannot be promoted in society … she could not climb the corporate ladder …” (Duncan, ‘Kirino Interview’).

Ultimately, this novel excels in showing its audience how industry in Japan is not only exploitative of human beings as a species, but also of these marginalised groups in society. The four women central to the plot are offered no place to turn to for comfort; their home lives are disastrous, and so I think what Kirino really achieves here is an illustration of how biopower can take real effect over a person’s, or, by extension, a woman’s life in this case and develops into “the ‘real subsumption of life’” (qtd. in Anderson 32).

There seems to be no break between the work life and the domestic in Kirino’s novel and I think this is excellently summarised in Yoshie’s defeatist statement: there really is no difference between the living and the dead in this society; each person is nothing but an object, a part in the machine that further propels the growth and expansion of biopower.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Kirino, Natsuo. Out. Vintage , 2006.

Secondary Sources:

Anderson, Ben. “Affect and Biopower: Towards a Politics of Life.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012, pp. 28–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41427926. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Duncan, Andrew. “Natsuo Kirino Interview.” Natsuo Kirino Interview | IndieBound.Org, www.indiebound.org/author-interviews/kirinonatsuo. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Foucault, Michel, et al. “Eleven 17 March 1976.” “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76, Picador, New York, New York, 2003, pp. 239–264.

French, Howard W. “A Tokyo Novelist Mixes Felonies with Feminism.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 Nov. 2003, www.nytimes.com/2003/11/17/books/a-tokyo-novelist-mixes-felonies-with-feminism.html.

This reading of Kirino’s ‘Out’ has shed light on some of the more complex aspects of the text, and shown its relatability to some of the other texts on the module. Your idea of the body as an economic transaction shows that the text is partially compatibility with Ling Ma’s ‘Severance’, each of these texts containing reference to Asian societies. Both of these texts staunchly warn the reader of the woes of capitalism, and the particular effect of this throughout ‘Out’ is made clear through your reference to the “soul-destroying … labour in contemporary Japan,” highlighting the “detachment of bodies from their autonomy.” This is relatable to the conditions of the workers discussed in Ma’s ‘Severance’, each working themselves to illness in maddening, repetitive conditions (as seen in the scenario involving Balthasar). I begin to see further comparisons as your blog continues, developing through reference to Foucault’s biopolitics in relation to such conditions. Your discussion of humankind being removed from the body and transformed into “species” brings to life the image of animalistic treatment of workers in such conditions (Asia being a particularly troublesome area in relation to child and sweatshop labour). Your concluding remark on Yoshie’s defeatist statement almost parallels the world of Ma, with ‘Severance’ showing both the living and the dead to be practically identical in her use of ‘Shen Fever’. This leads to the predominant question around the justification of the behaviour of the women throughout ‘Out’ – If the conditions of life are as terrible as described throughout both the text and your blog, then one cannot be faulted in holding a certain degree of sympathy for many of the characters. This post has been beneficial to my understanding of some of the text’s key messages, and shown ‘Out’ to be one of the most important novels of the twenty-first century!

I find it really interesting how you draw the comparisons between ‘Severance’ and ‘Out’ in terms of their related ethnic backgrounds, and how culture in the Asian continent regarding labour and capitalism influences the crises in their respective texts. Indeed, what both Ma and Kirino tease out in their equally disturbing yet vastly different novels is the idea that humans can never seem to escape capitalism; their lives are so deeply tangled and woven into its folds that to exist outside of its grips is impossible – in ‘Out’, it seems unattainable and a complete myth to achieve a comfortable and pleasant life, and in ‘Severance’, the time for that life has passed, and the likes of Candace and her ‘group’ are left to exist in the carcass of a typical embodiment of capitalism … a shopping centre. There exists within both of these texts an exploration of the ‘zombification’ of human life by capitalist structures like the factory space or the office space, how humans become what Kaiama Glover has described as a “thingified no-person” who is “reduced to its productive capacity” (Dillon “Zombie Biopolitics” 626) and an overall foreboding that even when the system collapses and the world is run riot with Shen Fever or an intense craving for a “Lunch of Champions” bento box, there is no entanglement from the capitalist web.

Excellent post on the targeting of human life in Kirino’s Out – the extent to which human are reduced to things or objects (which Yoshie first moots on or around p.95) and the implications of such a move. Kirino would seem to want to underscore the primacy of the economic realm here, at least in the first part of the novel which focuses very much on ‘the productive forces’ to use a Marxist term. The alienation of the workforce in these early chapters very much speaks to Marx’s thoughts on ‘estranged labour’ (i.e. the worker as alienated from themselves and the thing or object being produced). But I wonder how far the novel supports this Marxist reading and how gender and/or ethnicity enter the argument, along the lines you suggest. The relevance of Foucault’s understanding of biopolitics, as developed in these later lectures, is hard to deny but Foucault was by no means a Marxist and always sought to expand or extend his claims about power beyond the economic – a point that would seem to connect nicely to your argument about Out’s society-level object-targeting, to borrow Anderson’s phrase. To think about a reading of Out that moves carefully between Marx and Foucault is a daunting proposition but I think you’re already most of the way along this path.

..

I really enjoyed reading your interesting post Eimear! I like how you connected the novel with Foucault’s concept of biopolitics. In particular, you engage with Foucault’s thinking around the broadening of the rights of sovereignty in which the technologies of power became concerned with “man-as-species”, a change that emerged from the proliferation of species-discourses surrounding the administration of all life: death rates, fertility, life expectancy etc. As you point out, Kirino concieves of her female workers through such a biopolitical lens, transforming them into “one singular body” defined by their capacity to produce and generate earnings. In this sense, the women are demoted to the status of literal human capital. Kirino’s reification of the human into an object valued only for its economic utility is blatantly apparent in the women’s body-cutting business which, as you highlight, ascribes bodies with exchange value; life and death become transactional in the novel. Kiriono returns to this idea at the dramatic climax of her novel which finds Masako tied to a conveyor belt at the deserted, replica factor. Here Kirino offers an explicit critique of biopolitical control as Masako becomes, quite literally, a commodified product in the culture of death.

Eimear, I really enjoyed your blog post! Your conception and analysis of Kirino’s positioning of the body was incredibly insightful, in particular when you note “Seeing the workers as nothing more than a “species” reduces them to little more than one singular body made valuable through the volume of production that it can achieve”. As you go on to suggest, transaction comes to mind; Kirino situates the murder as another job, further defiling a sense of the ‘human’. The suggestion that the body-chopping is just another job enacts questions surrounding crime and sympathy. Do we view the body-chopping as a crime, that then spirals? Naturally, crime evokes legality, yet Kirino homes in on the moral aspect of the act. How are we positioned? I wonder whether we are we placed to sympathise with the women? Is Kirino successful in this positioning?

Your excellent discussion of biopolitics in Out illuminate the precarious distinction between an object and a human body. The idea of objects and dead bodies as non-human entities stretches into other domains that constantly redirect focus to the inhumane treatment of humans in the novel. Kirino seems to comment on the alienating forces of labour and describes the cold, empty lives of the factory workers. The characters’ lives are devoid of any positivity or warmth and I think that this results in a narrative that leaves no room for the interpretation of emotions or affect. In some ways, the dreadful circumstances become monotone and the reader grows accustomed to them. However, I do think that the combination of affect theory and Foucault’s biopolitics could be an interesting approach as well.

I was really interested by your discussion around bodies as nothing more than economic transactions and how the treatment of life and death is so removed from humane. The business-like approach that you picked up on really surprised me when I first read it. Amidst the graphic descriptions of meat and blood and how exactly the body was disposed of there is a frankness of dialogue that is so jarring given the circumstances : “It was a human being, but now it’s an object”. When reading this blog post, I was struck by the similarities to a later text on the module; Sabrina. The nonchalant attitude towards death is prevalent in both and how we have become so desensitised to violence. In “Out” this is for survival whereas in Sabrina it is learned through our cultural addiction to the online world.