And then we’re all objects – the living and the dead. There’s no difference.

(95)

As she kneels over Kenji’s dead body, preparing to chop it up, Yoshie summarises for readers one of the central tenets of Natsuo Kirino’s disturbing Out, which is a plot driven by the author’s investigation and critique of life in modern Japan. In this novel, bodies are nothing more than an economic transaction in the world of baccarat clubs, bento-box factories and the bathrooms of your colleague’s house, where you can get your husband chopped up with a sashimi knife for a price.

Kirino truly succeeds in illustrating the dire conditions endured by her protagonists and using them as a vehicle to portray the soul-destroying effects of labour in contemporary Japan, and I see this largely being achieved by her complete (and literal) detachment of bodies from their autonomy and transforming them into something a little more “businesslike” (97).

(Natsuo Kirino for Makoto Watanabe)

The concept of ‘the body’ in the novel is so far removed from the humane that it is possible in Kirino’s imagining of the Tokyo suburbs that anybody can literally be belittled and reduced to nothing more than any other body, some mutilated flesh in a shopping bag in exchange for some 500,000 yen.

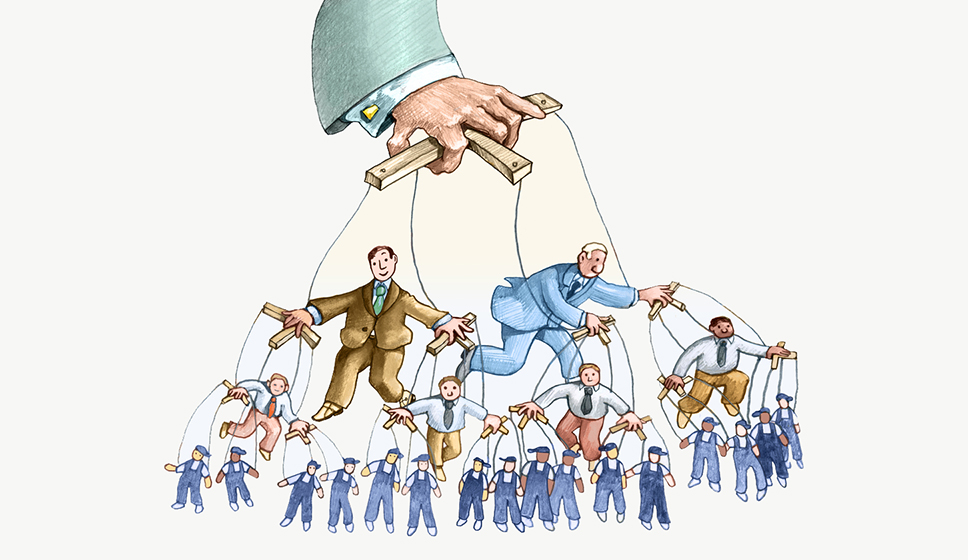

The transactions of bodies we see in this text reflect and critique the role they perform as a cog in the wheel of human capitalism in the industrial world of Japan. While reading this text, I felt Michel Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and biopower taking centre stage in how the Japanese culture of industry is illustrated as being powerful and having a central role in the lives and the survival of our characters. These characters work in dire conditions that see them “standing on the cold concrete floor” (Kirino 11) for hours at a time, with “a replacement filling in on the line” as they run for bathroom breaks. The characters are portrayed as having accepted this as their reality and have assumed a rather docile position in the workplace.

This was the secret to lasting at a place like this without ruining your health.

11

It seems that the factory views its staff as a body of work that makes up one labour force, working as a “team” (Kirino 11) to achieve mass production for low costs. This level of control is reminiscent of what Foucault said in one of his lectures at the Collège de France, that “a … seizure of power … is directed not at man-as-body but at man-as-species … a “biopolitics” of the human race” (Society Must Be Defended 243). Seeing the workers as nothing more than a “species” reduces them to little more than one singular body made valuable through the volume of production that it can achieve.

There’s a transaction at play here: the workers surrender their dignity and their humanity to the machine in exchange for low pay and, arguably, escape from their depressing home lives. The machine, in turn, exploits their ‘humanness’ and, with that, their capabilities to function as one large workforce in order to achieve maximum production.

Ben Anderson’s idea of “the ‘object-target’” (‘Affect and Biopower’ 28) is an interesting lens for this text and looking at how the central characters of Out pertain to and adhere to this definition uniquely because of their marginality, highlights the formative role they play in the “contemporary forms of biopower” (29) in industrial Japan. Readers are made starkly aware of how easily reduced human beings can be to a mass of life that is quantified and used as a resource for the state. Human life, as we see it in Out, has “become the ‘object-target’ for specific techniques and technologies of power” (Anderson 28).

In his observation here, Anderson is referring to the concept of biopower, which is slippery in its frustratingly variable definition but broadly translates to the power over life. I find it really intriguing how Kirino’s depiction of biopower and biopolitics does not give a blanket illustration of this control over Japanese lives. Rather, she offers nuanced insights into how biopower is engaged with very marginalised groups like the Brazilian-Japanese population and the four women that are the focal point of the plot.

… if your husband is white-collar, the wife is blue …

New york times

In an interview with the New York Times, Kirino remarks on how the status of the woman in Japanese society “inevitably remains a rung below” (French, “A Tokyo Novelist Mixes Felonies with Feminism”). It is interesting how Kirino’s writing asks readers to look between the lines here and see how industry in Japan takes advantage of these groups of people who are unable to upskill and are given no alternative but to work in unskilled labour. I believe this is why Masako seems to be given a central role in the novel as Kirino has noted that Masako “is a symbol of Japanese women who cannot be promoted in society … she could not climb the corporate ladder …” (Duncan, ‘Kirino Interview’).

Ultimately, this novel excels in showing its audience how industry in Japan is not only exploitative of human beings as a species, but also of these marginalised groups in society. The four women central to the plot are offered no place to turn to for comfort; their home lives are disastrous, and so I think what Kirino really achieves here is an illustration of how biopower can take real effect over a person’s, or, by extension, a woman’s life in this case and develops into “the ‘real subsumption of life’” (qtd. in Anderson 32).

There seems to be no break between the work life and the domestic in Kirino’s novel and I think this is excellently summarised in Yoshie’s defeatist statement: there really is no difference between the living and the dead in this society; each person is nothing but an object, a part in the machine that further propels the growth and expansion of biopower.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Kirino, Natsuo. Out. Vintage , 2006.

Secondary Sources:

Anderson, Ben. “Affect and Biopower: Towards a Politics of Life.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012, pp. 28–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41427926. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Duncan, Andrew. “Natsuo Kirino Interview.” Natsuo Kirino Interview | IndieBound.Org, www.indiebound.org/author-interviews/kirinonatsuo. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Foucault, Michel, et al. “Eleven 17 March 1976.” “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76, Picador, New York, New York, 2003, pp. 239–264.

French, Howard W. “A Tokyo Novelist Mixes Felonies with Feminism.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 Nov. 2003, www.nytimes.com/2003/11/17/books/a-tokyo-novelist-mixes-felonies-with-feminism.html.