The US government ignored prior warnings of the 9/11 attacks, to justify their subsequent Middle East invasions. ‘Climate change’ is a political (particularly Democrat) invention used to garner financial or ideological support. Medical vaccines are poisonous, causing fatal adverse effects, and are thus used to depopulate the earth. US mass shootings are staged performances to enforce gun control laws in governmental attempts to acquire deeper societal control.

These are but a few of the dangerous conspiracy theories that remain popular within twenty-first century discussions, believed by disconcertingly large quantities of individuals.

Many such conspiracies are upheld in America, by groups believing their government to be “…hijacked by external/foreign powers … looking to promote a ‘New World Order’,” whilst holding: “In order to facilitate this [Order] … the government is interested in undermining the power of those who oppose it, by eroding constitutional rights,” (Sweeney & Perliger 54). Throughout his graphic novel Sabrina, Nick Drnaso alludes to real contemporary events that bred conspiracies, also creating his own conspiracy around a fictional murder. In doing so, he profoundly demonstrates the psychological instability of those who promote harmful theories surrounding traumatic events, and the damage they cause to their irrational accepters.

(YouTube)

Within Sabrina, we witness the lives of Calvin and Sandra become harmed by conspiratorial speculations, receiving threats like: “Someone should kill you,” (120) and: “Your address is online[,] … I’m armed and protected. See what happens if they … test me,” (155) as Sabrina’s existence becomes questioned. While each suffer greatly, Teddy (Sabrina’s partner) falls most susceptible to the effects of conspiracy throughout, becoming both a target of the paranoid mob and a succumbing absorber of its deluded mentality.

Someone is at fault. Someone is scheming and capitalizing big time. To … expose the conspirators for the thieving murderers they are; that is my vocation.

Douglas’ Conspiratorial Voice (p.89)

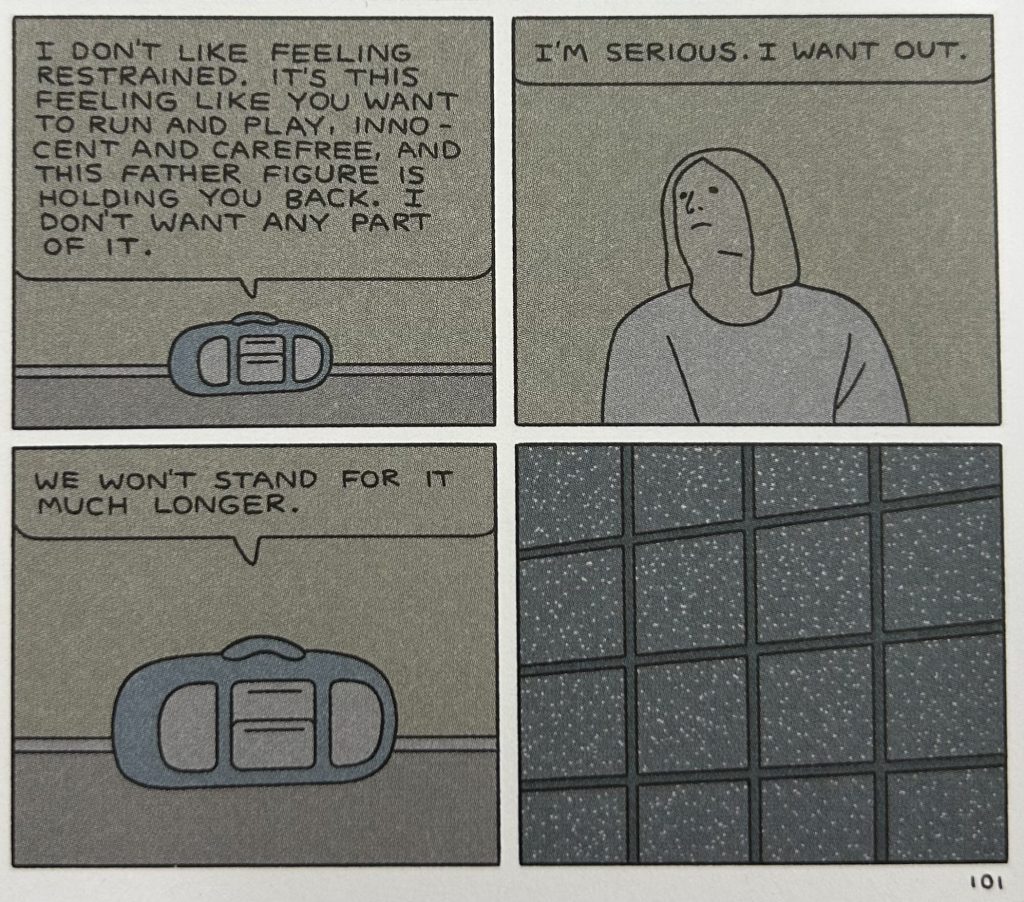

Many conspiracy theories seem “…product[s] of mental illness,” with “…some people who accept [them being] mentally ill and subject to delusions,” (Sunstein & Vermeule 211) which relates to Teddy. Following his introduction, I sympathise with Teddy’s grief-induced sombreness and unwell, dishevelled constitution. His digressions from silence (13), vomiting (37), and nightmares (46) into nervous exhaustion (52) factor into his susceptibility to the neurotic conspiracies of Albert Douglas, voiced on the radio. Douglas characterises an unhealthy conspiracist, discussing “…doomsday predictions,” and “…a global dictatorship,” whilst claiming: “Our masters will flee to their compounds, leaving us to endure unimaginable plagues…” (88). Not coincidentally, such provocative language resembles that of contemporary right-wing conspiracists like Alex Jones and the QAnon movement.

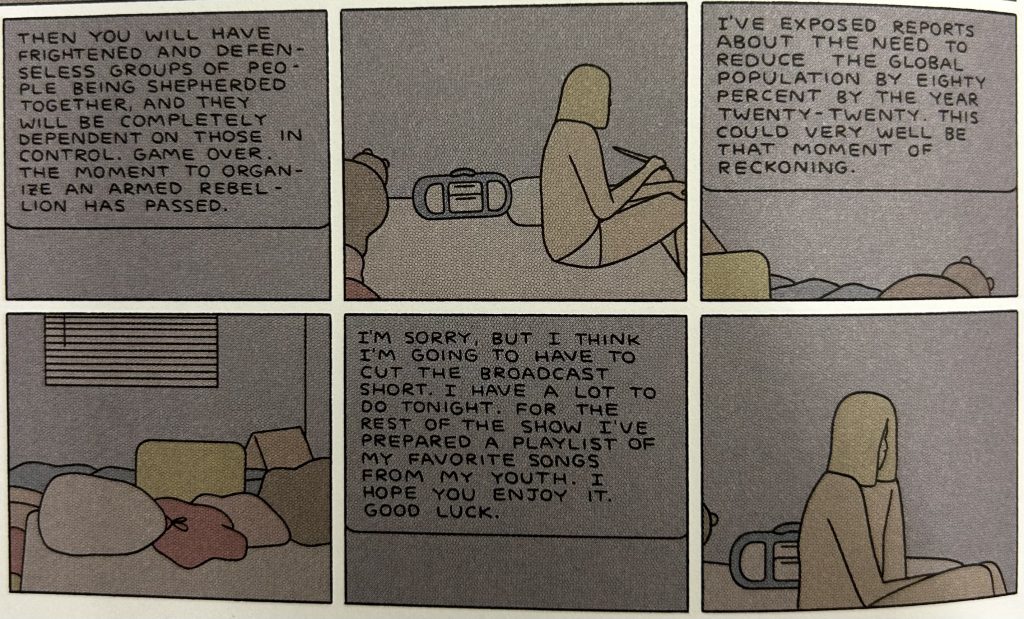

Throughout Sabrina, Douglas’ voice acts supernaturally, being both “…disembodied,” and “…omnipresent,” (Jacobs 72). Ironically, this demeanour transforms Douglas into his worst fear – a malevolent composer that “…stir[s] the pot, to keep [people] separate, suspicious, and hostile,” (88). Relatedly, Oliver and Wood highlight how many Americans “…consistently endorse some kind of conspiratorial narrative about a current political event … [with their] attitudes [being] predicted by supernatural … sentiments,” (953). Such sentiments often revolve around a battle of free humanity against a corrupt, enslaving force, presumably having “…seeds in the fall of the Twin Towers,” (Park §7) highlighted through Drnaso’s allusion to the event. Douglas incites this paranoia, arguing society will have “…defenceless groups of people being shepherded together, and … completely dependent on those in control,” (138) psychologically hauling Teddy into his state of mind. In this sense, Douglas becomes the “…spokesman of the paranoid style,” who “…finds [the conspiratorial world] directed against a nation, a culture, a way of life whose fate affects not himself alone but millions of others,” kindling Teddy’s devolution into a “…clinical paranoic,” that “…sees the hostile and conspiratorial world … as directed specifically against him,” (Hofstadter 4).

Although Douglas claims Sabrina’s murder to “…ha[ve] all the hallmarks of the [routine] staged tragedies,” (108) Teddy remains susceptible to his suspicions. However, notably: “…most people will only express conspiracist beliefs after they encounter a conspiratorial narrative that gives ‘voice’ to their underlying predispositions, assuming the particular incident was unusual … enough to invoke these feelings,” (Oliver & Wood 955) which applies to Teddy. Douglas discusses how he “…[doesn’t] believe … that Sabrina … was murdered by Timmy Yancey,” while posing: “For all we know, she’s alive in bondage somewhere … [or] [m]aybe forces too evil to comprehend did in fact murder [her],” (117) thereby provoking Teddy’s irrationality on two levels. Firstly, Teddy holds onto the possibility that Sabrina is alive, being kept in an area like the referenced “…black site,” (132). On the other hand, Teddy believes that Sabrina’s murder may have been performed by such veiled, heinous figures as described. This highlights the complex nature of conspiracism with trauma, with Teddy’s denial and longing for explanation contributing to his gullible vulnerability.

Eventually, his mistrust peaks, as Douglas’ ‘warnings’ of “…troops … announc[ing] a state of emergency … [and] shut[ting] down the power grid … [thus] keep[ing] the population under control,” (138) take thorough effect, leading Teddy to steal a kitchen knife for protection (135). Thus, through Teddy, Drnaso shows the parasitic nature of conspiracy, particularly within fixated, traumatised, and isolated individuals.

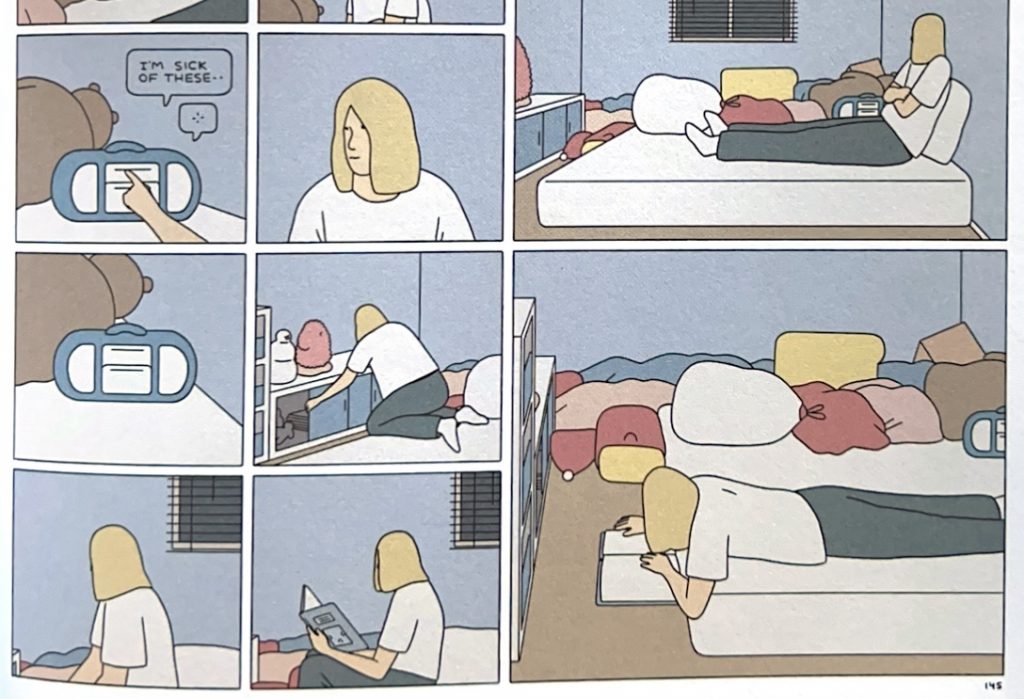

Thankfully, Teddy eventually switches off the radio, and begins reading an academic book designed for children (145). In this humorous implication, Drnaso suggests that there is more educational value in a children’s book than in such ramblings as Douglas’. Despite Teddy’s somewhat contented ending, however, we are left sympathising with those affected by the conspiracy, as Sandra and Calvin remain threatened and isolated, personifying melancholy.

Ultimately, Sabrina warns us to reject catastrophic conspiratorial perspectives, and to instead focus on empathy, rationality, and community. Can empathy be felt for Douglas himself, however? We see remnants of his humanity remain, unashamedly stating: “Thanks for giving me strength, mom. I love you,” (89). Furthermore, he “…served in the army during the Gulf War,” (121) perhaps being similarly traumatised, yet unable to escape the conspiracy cesspit before it consumed him. While this doesn’t justify Douglas’ scaremongering, it certainly sends Drnaso’s ambiguous text into deeper levels of interpretability. Maybe, to avoid being similarly seduced by conspiracies in our volatile contemporary period, we should heed Sabrina’s advice to “…get away from the internet,” (8) and preoccupy our minds with rewarding, satisfactory activities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PRIMARY SOURCE

Drnaso, Nick. Sabrina. Granta Publications, 2018.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Hofstadter, Richard. “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays, Vintage Books, New York, United States of America, 1967, pp. 3–40.

Jacobs, Rita D. “Review: Sabrina by Nick Drnaso.” World Literature Today, vol. 96, no. 6, 2018, pp. 72–73.

Oliver, J. Eric, and Thomas J. Wood. “Conspiracy Theories and the Paranoid Style(s) of Mass Opinion.” American Journal of Political Science, vol. 58, no. 4, Oct. 2014, pp. 952–966.

Park, Ed. “Can You Illustrate Emotional Absence? These Graphic Novels Do.” The New York Times, 31 May 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/31/books/review/nick-drnaso-sabrina.html. Accessed 14 Nov. 2023.

Sunstein, Cass R., and Adrian Vermeule. “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures.” The Journal of Political Philosophy, vol. 17, no. 2, 2009, pp. 202–227.

Sweeney, Matthew M., and Arie Perliger. “Explaining the Spontaneous Nature of Far-Right Violence in the United States.” Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 12, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 52–71.