But between these posts, something catches your eye: a video of grotesque violence that rocks you to your very core.

Yet, you can’t look away.

Let me set a scene: it’s late and you’re doom-scrolling through social media posts the algorithm has generated for you, ranging from tailor-made advertisements for the “sustainable” clothing that was made in an Asian sweatshop, to posts by that girl you sort of know who is now on her fourth holiday this year, yet the retail pay-check doesn’t quite explain how she’s currently sunbathing in Monaco.

But between these posts, something catches your eye: a video of grotesque violence that rocks you to your very core.

Yet, you can’t look away. And before you know it, three minutes and thirty-six seconds have passed, the video has ended, and an advertisement for face cream plays next.

In the early days of the internet, it was grainy CCTV footage of workplace accidents in which blood is but a smattering of red pixels; perhaps it was terrorist-related violence, the beheading of an individual in their final moments; or perhaps it’s brutal car crashes being turned into internet memes, sick laughter emerging from suffering. Irrespective of whatever format it took, I am certain you have experienced or will experience, such a thing in your modern life.

But why didn’t you look away?

Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, a chilling graphic novel, perfectly encapsulates this stranglehold violence has on us, aiming to convey the issue our society has with “consuming” violence, and the emotional numbness this creates, with a The New Yorker article interviewing Drnaso stating that he “has spent many hours in the darker corners of the internet”, alongside a quote from himself that there is “a morbid curiosity in [him]” (Max).

No blood, no grisly details. Just nonchalant descriptions of death.

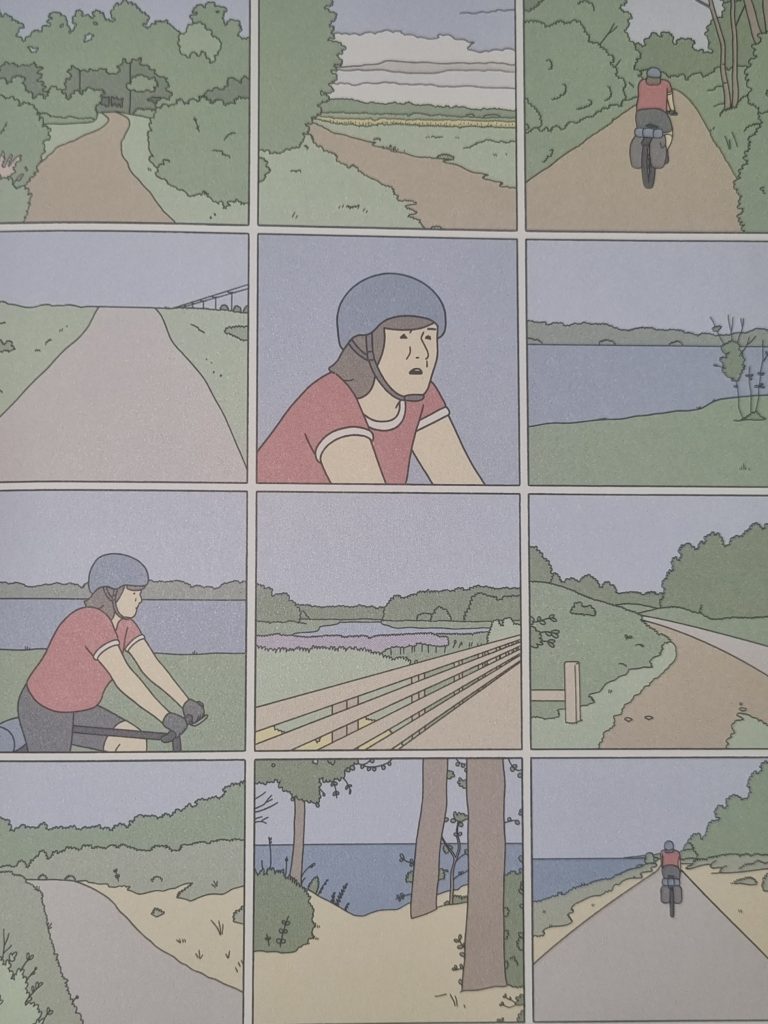

Within Sabrina, Nick Drnaso portrays a world in which, like our own, violence is never far away. The novel details the murder of the titular Sabrina Gallo, and portrays the aftermath of the incident on her boyfriend Teddy, who goes to stay with old friend Calvin, with both men experiencing crises in their lives due to conspiracy theories surrounding Sabrina’s murder.

Yet, despite Sabrina being a graphic novel, there are no real visuals of violence; instead, we are presented with characters reacting to or discussing it, with these very acts depicted outside of our periphery. Sabrina’s death is never actually described for the reader, not that it really needs to be. Instead, we are informed of her death through third parties, relayed information by journalists who state, “We just received a tape at our office that appears to show a young woman being murdered” (69). No blood, no grisly details. Just nonchalant descriptions of death.

“We just received a tape at our office that appears to show a young woman being murdered”

Nick drnaso, sabrina. page 69

In the pages that follow, detectives investigate the scene of the crime, with little dialogue uttered and minimal violence visually portrayed. But what startles most is the depiction of these detectives through Drnaso’s illustrations, the simplistic style mirroring that of workplace training videos, in which they are entirely unphased by what has occurred around them. In some panels, they even appear to have smiles on their faces (Page 72), entirely disaffected by the violence witnessed.

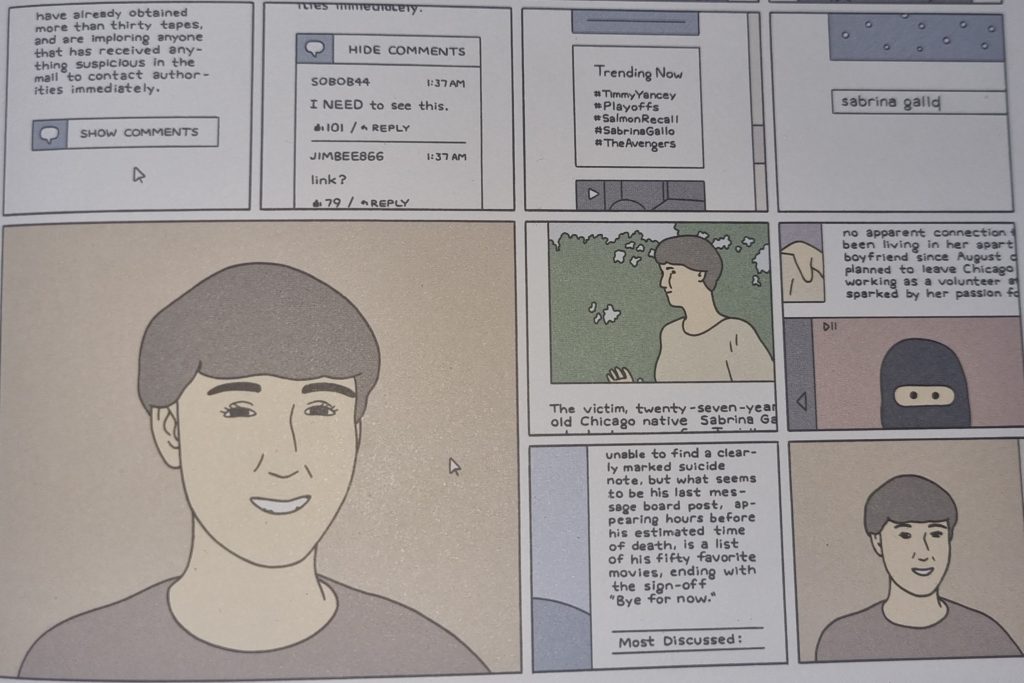

Later in the novel, Calvin uses social media to find information on Timmy Yancey, Sabrina’s murderer, with Dsrano illustrating a trending social media page in which Timmy and Sabrina’s names are the first and fourth most trending topics on the platform, respectively, accompanied by other consumable medias such as sports matches and superhero movies. (Page 81)

In the panel beside this, however, is a chilling message; an unnamed individual, replying to posts about Timmy with the comment “I NEED to see this”. (Page 81)

“I NEED to see this”

Nick drnaso, Sabrina. Page 81

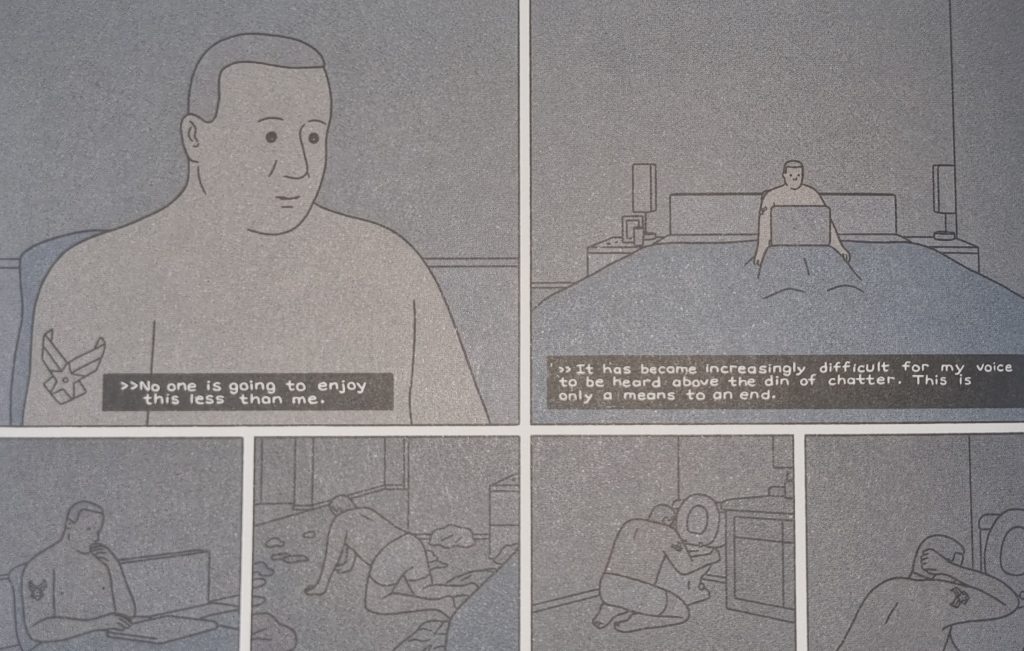

What follows is Calvin himself seeking out this video, for what purpose we do not know. We are never shown the video itself, but rather the aftermath, in which Calvin is physically sick. The only description we have is presumably Timmy’s voiceover during the video, in which he states that such violence “is only a means to an end” in a last-ditch attempt to be heard (Page 114).

But why didn’t Calvin look away?

In research conducted at Trinity College, Simon McCarthy-Jones discusses those who watch such acts of violence, coining them “white knucklers”, in that “like adrenaline junkies, they feel intense emotions […] but they dislike these emotions. They tolerate it because they feel it helps them learn something about how to survive” (McCarthy-Jones). McCarthy-Jones discusses these portrayals of violence as an educational experience, comparing them to the way that “‘painful’ cringe comedies may teach us social skills, watching violence may teach us survival skills” (McCarthy-Jones). Therefore, is the viewing of this violence by Calvin an act of morbid curiosity to “strengthen” himself? In turn, is this our subconscious thought behind why we too can’t look away from such videos?

“White knucklers… [are] like adrenaline junkies, they feel intense emotions […] but they dislike these emotions. they tolerate it because they feel it helps them learn something about how to survive”

Simon mccarthy-jones, trinity college dublin

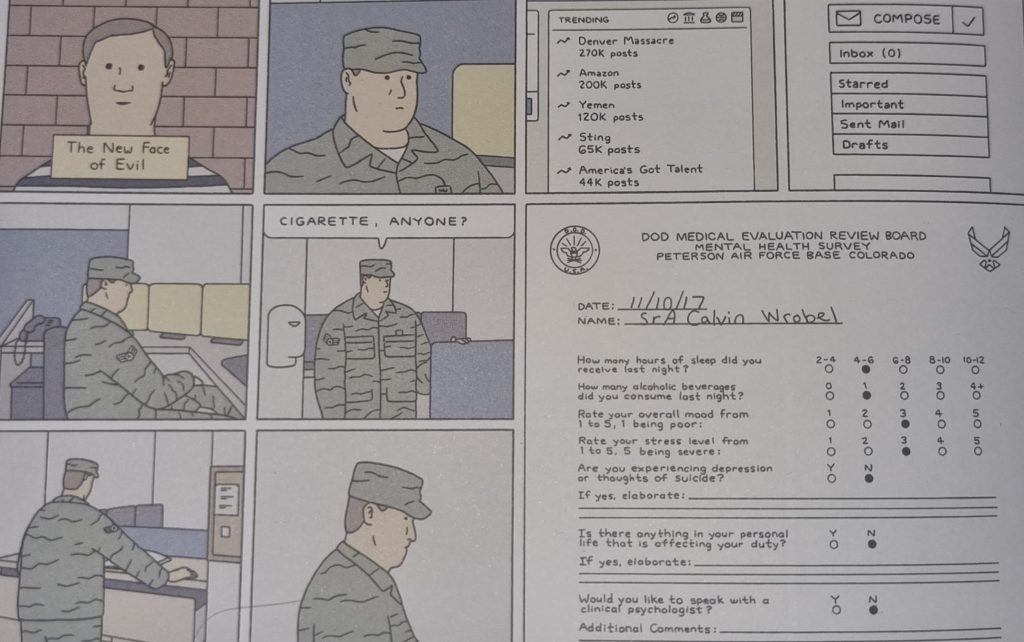

As later events in the novel unfold, the ever-looming presence of violence continues to feel all too real. Yet, Calvin becomes ever-more desensitized, unfazed by the events in the world surrounding him. At work, Calvin and his fellow airmen discuss a domestic terrorist “stream[ing] this video on Facebook, then killed everyone in a daycare centre and himself” (Page 143). Through Drnaso’s art, we see that the airmen, like the detectives, are entirely numb to this violence, eliciting no emotion, despite the personal relevance to Calvin, as his daughter is the same age.

Is the viewing of this violence by Calvin an act of morbid curiosity to “strengthen” himself? In turn, is this our subconscious thought behind why we too can’t look away from such videos?

However, what follows next is more chilling – in the panels that follow, Calvin views a social media trending page, in which this “Denver Massacre” is number one. Although we are left in the unknown as to whether he views the video, his nonchalant question of “Cigarette, anyone?” and his psychological evaluation as middle-of-the-road (both Page 144) both perfectly encapsulate the numbness Calvin possesses towards these acts of violence now. Through their readily available proximity online, these videos have erased empathy, disgust and emotion from his character, reflective of wider society at large.

Through their readily available proximity online, these videos have erased empathy, disgust and emotion from his character, reflective of wider society at large.

Therefore, I suggest that Drnaso’s portrayal of violence is an act of reflection, forcing his readers to question why we watch violence, and why we seek out such videos that are depicted in the novel. In her review of Sabrina, Rita D. Jacobs remarks that the “power of the graphic novel to dissect and examine our cultural moment is indisputable” (Jacobs), supporting the idea what is visually illustrated on the page is equally as crucial as Drnaso’s writing.

“The murder is incidental to the chilling indictment at the heart of the narrative – that of what our society has become”

Rita D. Jacobs, in her review for world literature today

However, Jacobs’ claim that “the murder is incidental to the chilling indictment at the heart of the narrative – that of what our society has become” (Jacobs) ultimately embodies what I believe to be the most important facet of this novel’s story; it is not a narrative that occupies itself with Sabrina’s death, nor the wider loss of life elsewhere in the novel. Rather, it focuses on the aftermath of such violence, exploring the societal ramifications, and portraying the personal numbness the individual experiences upon viewing and “consuming” these acts of violence.

Bibliography

Primary Text

Drnaso, Nick. Sabrina. London Granta, 2018.

Secondary Texts

D. Jacobs, Rita. “Sabrina by Nick Drnaso.” World Literature Today, 2018, www.worldliteraturetoday.org/2018/november/sabrina-nick-drnaso. Accessed 14 Nov. 2023.

Max, D. T. “The Bleak Brilliance of Nick Drnaso’s Graphic Novels.” The New Yorker, 14 Jan. 2019, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/21/the-bleak-brilliance-of-nick-drnasos-graphic-novels.

McCarthy-Jones, Simon. “From Tarantino to Squid Game: Why Do so Many People Enjoy Violence?” The Conversation, 28 Oct. 2021, theconversation.com/from-tarantino-to-squid-game-why-do-so-many-people-enjoy-violence-170251.

Roach, Jason, et al. “Dealing with the Unthinkable: A Study of the Cognitive and Emotional Stress of Adult and Child Homicide Investigations on Police Investigators.” Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, vol. 32, no. 3, Nov. 2016, pp. 251–62, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-016-9218-5.

You made a very insightful point that violence is never explicitly shown on the comic strip but it is the foundation of the graphic novel through characters continually discussing it. This is because our cultural fascination with the grotesque has rendered violence as largely “normal”. This leads to a desensitisation to the world around us; we never really experience anything deeply because we retain a distance from it. This is particularly true on social media as we can consume posts and videos showcasing horrific violence but can at any moment step back from it. This is particularly easy when it is happening across the world as our comfortable reality is not affected. This is mirrored in Calvin’s emotionless response to the Denver Massacre. This is at the heart of Drnaso’s critique because we live so much in the online world that it creates a disconnection from the real world and the people who live in it.

I feel there’s something very profoundly scary about the violence not actually being visually depicted. Perhaps it has to do with that cultural obsession with the grotesque – maybe Drnaso wants us to play with out contemporary cultural knowledge of violence, and render these images for ourselves. Perhaps this is the true desensitization within the contemporary – that such violent images in novels such as Sabrina don’t need to be produced, rather we can probably create an equal, if not more terrifying image, from drawing upon things that we ourselves have seen online.

I find your argument that the portrayal of violence is an act of reflection forcing us to question why we watch violence very interesting. Particularly when we consider this representation of violence in tandem with the violence presented in other novels from the course such as Whitehead’s ‘The Underground Railroad’ wherein violence seems to permeate every page and is a harrowing daily occurrence. There is a sense that there is a fetishisation of violence in modern contexts and as you rightly point out the readily available proximity online of violence erases empathy. I wonder if this is a modern vision of something that has permeated society for significantly longer than we would all care to admit. Whitehead shows us the extreme popularity of public executions and I feel Drnaso is highlighting an uncomfortable truth here. There is an inherent propensity for humans to not only inflict violence but watch it and what may seem archaic still exists in a contemporary setting and warrants interrogation. This is a very bleak train of thought I can only apologise but a very thought provoking blog nonetheless!

I really liked the subject of the post and the questions you’re asking about our fascination with violence – and how Sabrina deals with this fascination as a means of forcing us, as readers, to reflect on what drives our morbid curiosities. At one point you connected this curiosity and/or fascination to conspiracy theory and I wondered if this connection could be further developed. Conspiracy presents itself as an alternative form of knowledge but quickly unravels into a questioning of narrative itself, as a means of knowing things about the world. In this context, I wonder how Drnaso’s fascination with violence or fascination with our fascination with violence might relate to this distrust of traditional forms of authority – and what the implications might be for the work that narrative does to make sense of the world. Sabrina seems to ask some far-reaching questions about how we know what we know and wants to implicate the same rubbernecking tendencies that provoke people to look at violence in a certain way of seeing the world where we are encouraged to see threat, even if there is no threat.

This is an interesting discussion of Drnaso’s presentation of violence and its aftermath. You make an interesting point that for a book so central in its discussion of violence never depicts any visual violence, but we are described it through various media sources. I think the use of media in the novel is really interesting, the use of more formal news sites as well as social media are used to explore the same scenario through different tones of formality. Equally, the inclusion of comments on posts are crucial to Drnaso’s storytelling, and provide an interesting discourse surrounding online presence and its influence on societal behaviour. Do you think that social media and online personas have influenced our perception and reaction to violence? Drnaso presents a sort of sensationalism to violent media, one that is sustained and perpetuated through morbid online interest. In thinking of subversive reactions to violence I am reminded of the Ted Hughes poem ‘In Laughter’ which depicts horrific scenes of violence that are reacted to by laughing. The idea being a morbid fascination with violent displays that invoke a response that does seem appropriate. I wonder if Drnaso is following a similar idea by suggesting that the online reactions to Sabrina’s death are not a portrayal of a desensitised society but rather a display of subversive reaction in response to horrific and visual violence.

I loved reading your opinions on violence, our fascination and our reflections. When reading about violence I can’t help but think about Slavoj Žižek and his ‘Violence: Six Sideways Reflections’. A short extract from the work fits really well with what you are discussing above;

“What about animals slaughtered for our consumption? who among us would be able to continue eating pork chops after visiting a factory farm in which pigs are half-blind and cannot even properly walk, but are just fattened to be killed? And what about, say, torture and suffering of millions we know about, but choose to ignore? Imagine the effect of having to watch a snuff movie portraying what goes on thousands of times a day around the world: brutal acts of torture, the picking out of eyes, the crushing of testicles -the list cannot bear recounting. Would the watcher be able to continue going on as usual? Yes, but only if he or she were able somehow to forget -in an act which suspended symbolic efficiency -what had been witnessed. This forgetting entails a gesture of what is called fetishist disavowal: “I know it, but I don’t want to know that I know, so I don’t know.” I know it, but I refuse to fully assume the consequences of this knowledge, so that I can continue acting as if I don’t know it.

We love violence, but we pretend that we don’t, we are fascinated but act like we aren’t. Its a fascination that we truly don’t understand and in order to continue on with our lives we never truly assume the consequences of the violence in question.