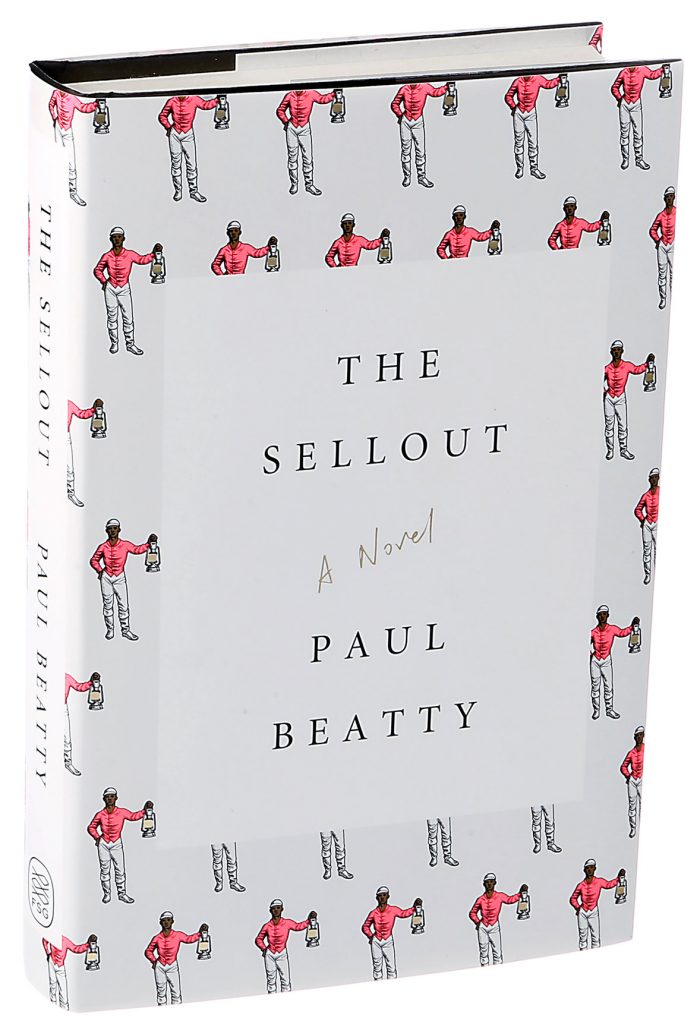

Paul Beatty’s 2015 novel The Sellout is preoccupied with exposing the limitations of contemporary attitudes towards race. Like all great works of satire, Beatty’s novel draws attention to the contradictions inherent in the social institutions and practices of his own culture through humour and irony. He does so to satirise the idea of a ‘post-racial’ America, to point out the gap between rhetoric and reality, between the claims of progress in Obama’s America and the reality of the racism that still exists in the twenty-first century.

Chapter Twenty of the novel concerns the building of a makeshift swimming pool. Beatty recollects that at the ‘height of the government enforcement of the Civil Rights Act’ (226) some towns in the United States ‘filled in their municipal pools’ (226) rather than suffer the horror of letting African-Americans swim alongside white people.

In light of this, the narrator hires someone to construct a ‘Whites Only swimming pool’ (226) in Dickens, surrounded by ‘a chain-link fence’ (226). The reason given for this bizarre construction is that the children of Dickens ‘loved to hop’ (226) the fence and ‘play Marco Polo’ (226) in the Whites Only pool.

The narrator seems to revel that his act of seemly racist segregation serves only to spur on enthusiastic resistance to that same segregation. Beatty indicates here that the reason behind the narrator’s attempt to re-segregate Dickens is ironically so that the people of Dickens will resist it, and in resisting it, realise the already segregated nature of the society that they live in.

By pointing out the reality behind the rhetoric, that the U.S.A. is still a heavily segregated society despite the end of formal segregation and Jim Crow, Beatty’s novel exposes the limitations of progressive anti-racism. In looking at race from a ‘colour-blind’ or ‘post-racial’ perspective, contemporary attempts to address race ignore the history and legacy of American racism, from segregation to slavery.

“[C]ontemporary attempts to address race ignore the history and legacy of American racism, from segregation to slavery”

Another incident that exposes the limitations in twenty-first century attempts to address race is The Sellout’s parody of Black History Month. In response to the ‘disingenuous pride and niche marketing’ (226) of Black History Month, the narrator converts an abandoned car wash into a ‘tunnel of whiteness’ (227).

The narrator relates how the children can choose between ‘several race wash options’ that include ‘Regular Whiteness’, ‘Deluxe Whiteness’ and ‘Super Deluxe Whiteness’ (227). Regular Whiteness includes the ‘Benefit of the Doubt’, Deluxe Whiteness includes ‘Warnings Instead of Arrests from the Police’, and Super Deluxe Whiteness includes ‘Legacy Admissions to College of Your Choice’ (227).

Here, The Sellout clearly satirises the privilege still enjoyed by white Americans in a ‘post-racial’ society, but Beatty also suggests the intersectional nature of white privilege. Professor Steven Delmagori suggests that by including the different versions of whiteness, all with their different privileges, The Sellout acknowledges the ‘class privilege immanent to white privilege’.

Beatty’s critique implies that all white people enjoy white privilege, but not all white people enjoy the same amount of white privilege. In doing so, Beatty ‘couples the whiteness critique to a class critique’ in a way that points out the flaws in the monolithic view of White Privilege in contemporary attempts to address racism.

At the end of the novel, the narrator sees Foy Cheshire celebrating Obama’s election. Foy says that America has finally ‘paid off its debts’ (289). The narrator responds: ‘And what about the Native Americans? What about the Chinese, the Japanese, the Mexicans, the poor, the forests, the water, the air, the fucking California condor? When do they collect?’ (289).

Dr. Henry Ivry of the University of Glasgow’s School of Critical Studies suggests that this moment encapsulates Beatty’s approach to race in the twenty-first century, in which ‘race doesn’t exist in a vacuum’, but rather is ‘a tangled category that intersects not only with other racialized beings but also with class, the environment, and even animals.’ The Sellout rejects the narrow parameters of contemporary conceptions of racism to explore the ways that race intersects with class, gender, ethnicity and ecology in order to approach a more robust account of race in the twenty-first century.

“The Sellout rejects the narrow parameters of contemporary conceptions of racism to explore the ways that race intersects with class, gender, ethnicity and ecology”

At the end of Chapter Twenty, the narrator travels to Dickens’ local hospital where he paints a ‘black or brown’ (231) line on the wall of the hospital that leads down three flights of stairs, and then to three different locations: ‘a back alley’, ‘the morgue’ and a ‘junk-food vending machine’ (231).

These lines satirise the inequalities faced by African-Americans and other minorities in the American healthcare system, with black and other minority people facing lower insurance rates and higher premiums (abandoned in the ‘back alley’), shorter life expectancy (‘the morgue’) and higher rates of obesity and diabetes (‘vending machine’).

Five years after the passing of the Affordable Care Act, Beatty’s novel emphasises both the disadvantages that black people still face in the American healthcare system and the discrimination that they face in medical treatment. The Sellout is preoccupied with questioning and exploring claims of racial progress, and suggests over and over that ‘post-racial’ rhetoric is just a cover for the unaddressed problems of American racism.

Bibliography

Beatty, Paul, The Sellout (London: Oneworld, 2015)

CDC, ‘Adult Obesity Facts’, 2021 <https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html> [accessed 3 Jan 2024]

Delmagori, Steven, ‘Super Deluxe Whiteness: Privilege Critique in Paul Beatty’s the Sellout’, Symplokē, 26.1-2 (2018), 417–25

Irvy, Henry, ‘Unmitigated Blackness: Paul Beatty’s Transscalar Critique’, ELH, 87.4 (2020), 1133–62

Lee, Paulyne, Maxine Le Saux, Rebecca Siegel, Monika Goyal, Chen Chen, Yan Ma, and others, ‘Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Management of Acute Pain in US Emergency Departments: Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review’, The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 37.9 (2019), 1770–77 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.014> [accessed 3 Jan 2024]

The Century Foundation, ‘Racism, Inequality, and Health Care for African Americans’, 2019 <https://tcf.org/content/report/racism-inequality-health-care-african-americans/?agreed=1> [accessed 2 Jan 2024]

The New York Times, ‘U.S. Life Expectancy Plunged in 2020, Especially for Black and Hispanic Americans’, 2021 <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/21/us/american-life-expectancy-report.html> [accessed 2 Jan 2024]