Dr Aisling Reid reports on her recent trip to Italy and her research into the pilgrims and Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy.

In canto fifteen of the Inferno, Dante encounters the author Brunetto Latini, who asks him how he has come to find this place and who it is that guides him on his path. Dante explains he had lost his way in a valley when his guide appeared to him to help lead him home again. Much like the protagonist Dante, medieval pilgrims left their domestic homes to travel through distant lands in search of their spiritual ‘homeland’.

The act of pilgrimage facilitated a spiritual encounter through physical surroundings. Among the most important medieval pilgrimage sites were Santiago de Compostela, Rome and Jerusalem. In the thirteenth century, many pilgrims travelled to Jerusalem by boats departing from Venice. The journey could be perilous; pilgrims risked sickness or drowning and the growing Turkish influence in the Orient limited the possibilities for travel. For those who did not wish to take such risks, or could not afford the cost, the ‘substitutive’ holy lands known as the Sacri Monti enabled Italian pilgrims to travel within the safer confines of their local area. Built in Piedmont and Lombardy between the fifteenth and the eighteenth centuries, the Sacri Monti comprise a series of chapels built across a mountain. Each chapel contains realistic painted statues made of wood and terracotta. Similar to the sculptural tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca, Guido Mazzoni and Antonio Begarelli, the statues within each chapel present a frozen moment in a religious narrative. There are fifteen Sacri Monti in Northern Italy:

| Sacri Monti | Place |

| La Nuova Gerusalemme | Varallo Sesia (Vercelli) |

| La Nuova Gerusalemme di S. Vivaldo | Montaione (Florence) |

| Santuario di S. Maria Assunta di Crea | Serralunga di Crea (Alessandria) |

| Sacro Monte di S. Francesco | Orta (Novara) |

| Sacro Monte | Varese |

| Sacro Monte di S. Carlo | Arona (Novara) |

| Santuario della B. V. di Loreto | Graglia (Vercelli) |

| Santuario della Madonna del Sasso | Orselina (Canton Ticino-Svizzera) |

| Santuario della Vergine Nera di Oropa | Biella (Vercelli) |

| Santuario della B. V. del Soccorso | Ossuccio (Como) |

| Santuario di S. Maria delle Grazie di Montrigone | Borgosesia (Vercelli) |

| Santuario della SS. Trinità | Ghiffa (Novara) |

| Sanro Monte Calvario | Domodossola (Novara) |

| Santuario di N. S. di Belmonte | Valperga Canavese (Turin) |

| Sacro Monte Addolorato | Brissago (Canton Ticino-Svizzera) |

The earliest ‘sacred mountain’ was built in Varallo in 1493 at the behest of a Franciscan brother, Bernardino Caimi. It featured a series of chapels which architecturally and geographically mimicked buildings found in the Holy land. For this reason, it was known as the ‘New Jersualem’. The project repositioned Jerusalem to offer visitors a sanitised pilgrimage within their local vicinity. Visitors would trek along the biblical sequence to witness the slaughter of the innocents, the last supper and the crucifixion. The project allowed pilgrims to insert themselves into an imagined past narrative to directly interact with the numinous; visitors could caress the Christ child in his cradle, or literally touch his wounded flesh. In this sense, the chapels provided an augmented form of reality which would not have been possible in the real Holy Land. Much like ‘The Holy Land Experience’, a modern faith based theme park in Orlando featuring a Via Dolorosa, Calvery’s Garden Tomb and regular re-enactments of the crucifixion, the Sacri Monti allowed pilgrims to realize a fantasy.

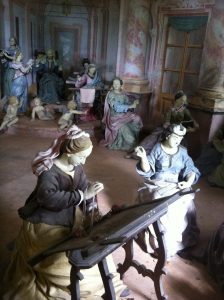

I recently stayed in the Santuario di Sant’Oropa outside Biella, which comprises twelve chapels dating to the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Each church contains sculptural scenes from the life of Mary, including her birth, her betrothal, the annunciation and the visitation, among others. A hundred years ago, the site was also visited by the English travel writer Samuel Butler, who recorded his trip in a 1881 work entitled ‘Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino’. Butler remarked that the chapels ‘aim at realism’; the narratives presented, however, improve on reality to rewrite the past into the present. The chapel of Mary’s sojourn at the temple, for example, presents the virgin within a distinct eighteenth century domestic setting, where she is shown among women who spin and sew. Butler compared the setting to a ‘high-toned academy for young gentlewomen’, where ‘all the young ladies are at work making mitres for the bishop, or working slippers in Berlin wool for the new curate’. The chapel thus shapes religious narrative into a format palatable to its original eighteenth century audience. The enduring appeal of the sanctuary is attested by the thousands of pilgrims who continue to visit the site each year, as well as the thousands of ex-votos which line the sanctuary’s corridors.

Fig 1. The Santuario d’Oropa

Fig 2. The chapels of the Sacro Monte at the Santuario d’Oropa

Fig 3. Inside the Chapel of the Sojourn of Mary at the Santuario d’Oropa

Fig 4. Curious goats guard the Sacro Monte chapels at the Santuario d’Oropa

Fig 5. The corridor of tavolette votive in the Santuario d’Oropa

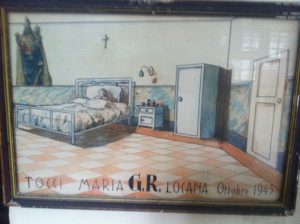

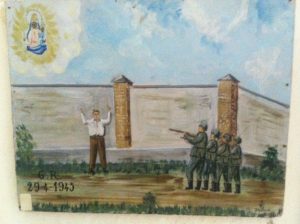

Fig 6. Votive offerings at the Santuario d’Oropa

Fig 7. Votive offerings at the Santuario d’Oropa

Fig 8. Votive tablet dedicated to the Black Madonna at the Santuario d’Oropa.

Fig 9. Votive tablet dedicated to the Black Madonna at the Santuatio d’Oropa.

Further literature and websites:

Webpage of the Santuario d’Oropa

Butler, Samuel. Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino. London: Jonathan Cape, 1931. Print.

De Boer, Wietse and Christine Cottler, eds. Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2013. Print.

Lasansky, D. Medina. “Body Elision: Acting out the Passion at the Italian Sacri Monti” in Hairston, Julia and Walter Stephens, eds. The Body in Early Modern Italy. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2010. Print.