Workshop Title:

Understanding Institutional and Residential Welfare and Public Health in Twentieth-Century Ireland and Britain

Friday 28 November 2014

Convenor: Dr Seán Lucey (AHRC Research Fellow, QUB, School of History & Anthropology)

All welcome but space is limited and booking with Dr Seán Lucey is essential. Email: d.s.lucey@qub.ac.uk. See below for abstracts.

Window of Mortuary at Bawnboy Workhouse, Co. Cavan. Photo: G. Laragy

This event is funded by QUB’s Institute for Collaborative Research in the Humanities’ Poverty and Famine in Ireland Research Group. The event is also supported by the Institute’s Health Humanities Research Group and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Description

Institutional and residential care in twentieth-century Ireland and Britain remains highly controversial. Inquiries into allegations of historic abuses ensure that the legacy of institutional/residential care remains to the fore of modern-day debates. Provision was often marked by punitive, abusive and disciplinary regimes. It is also evident, however, that institutions held a complex place in society and often provided much needed welfare and public health. This workshop aims to draw out nuanced understandings on the historical development of institutional and residential provision. Speakers focus on different institutional settings across Ireland and Britain including workhouses, prisons, hospitals, mental institutions, Magdalene Laundries and homes for mothers and children. The workshop also addresses the legacy of historic institutional/residential abuse from multidisciplinary perspectives. Papers critique inquiries and legal mechanisms that deal with abuse allegations through legal and social justice frameworks. The workshop includes social policy perspectives and addresses the past’s impact on future services.

Venue (NB: Note different am and pm locations)

9.00 am – 12.40 pm Irish Studies Seminar Room (Fitzwilliam Street, 6-8)

1.40 pm – 4.50 pm McClay Library (Training Room 2)

A map of QUB’s campus may be downloaded here

Programme

9.00 – 9.30: Registration

9.30 – 9.45: Introductory remarks: Dr Seán Lucey (QUB)

9.45 – 11.05: Inter-war workhouses: Slow erosion of the poor law

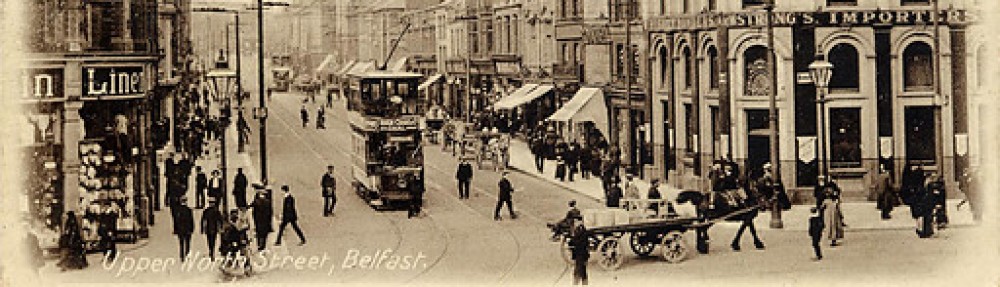

Dr Olwen Purdue (QUB) ‘A humiliating last resort? The role of the Union Workhouse in inter-war Belfast’

Prof Barry Doyle (University of Huddersfield) ‘Little more than a change of sign above the door? The development of non-acute medicine in provincial poor law hospitals, 1925-45’

11.05 – 11.20: Coffee

11.20 – 12.40: Prisons and Mental Institutions

Dr Ian Miller (Wellcome Trust Research Fellow, University of Ulster) ‘“I Would Have Gone on with the Hunger Strike, but Force Feeding I could not Take”: Hunger striking and prison welfare in English Prisons, c.1913-72

Dr Damien Brennan (Trinity College Dublin, School of Nursing and Midwifery), ‘From asylum to community health care: The migration of institutional structures and professional practice’

12.40 – 1.40: Lunch

1.40 – 3.00: Institutions and Women

Dr Leanne McCormick (University of Ulster) ‘In Trouble’: Managing maternity cases in early C20th Belfast’

Dr John Welshman (University of Lancaster) ‘Wardens, letter writing, and the early Welfare State’

3.00 – 4.20: Dealing with the Past and Institutional Abuse

Dr Anne-Marie McAlinden (QUB, School of Law) ‘Institutional Abuse in Ireland and Beyond: Public Inquiries, Truth Recovery and Restorative Justice’

Dr Katherine O’Donnell (University College Dublin, School of Social Justice) ‘“I believe the women”: Justice for Magdalenes and epistemic injustice’

4.20 – 4.50: Roundtable discussion and End

Abstracts

Dr Damien Brennan (Trinity College Dublin) From Asylum to Community Mental Health Care: The migration of institutional structures and professional practice

During the 1950’s the level of mental hospital usage in the Republic Ireland was the highest internationally with a rate of 710 beds per 100,000. These institutions provided ‘care’ to those categorised as ‘insane’, ‘mentally ill’ or having ‘mental health problems’ as it is now described. However, they also developed into locations of substantive social and economic importance to the communities in which they were situated.

This paper will demonstrate that this spectacular growth of mental hospital usage had little to do with the mental state of the individuals who were institutionalised. As such there was no epidemic of ‘mental illness’ in Ireland, rather this institutional confinement occurred in response to social forces (such as legislation, systems of admission and discharge, diagnostic criteria, social deprivation and family dynamics), along with the actions of the individuals, families and professional groups who directly carried out the act of committal.

This paper will also observe that the professional bodies who directly oversaw and enacted this enduring and wide scale programme of institutional detention have now secured the most predominant positions of control within contemporary mental health services. It will be argued that we must move beyond the legacy and professional structures of the old mental hospitals to ensure the achievement of quality Mental Health Services that are fit for purpose for contemporary society.

Prof Barry Doyle (University of Huddersfield) Little more than a change of sign above the door? The development of non-acute medicine in provincial poor law hospitals, 1925-45

In the early 1920s the majority of hospital beds in England were to be found in the sick wards and infirmaries of the poor law. Although originally intended to be institutions of last resort, by the late 19th century many workhouses were home to the aged, infirm and chronically ill – categories of patient eschewed by the voluntary hospitals. In the aftermath of the First World War these medical inmates came to dominate such institutions, a process accelerated by changes in welfare, life expectancy and attitudes to hospital treatment. Yet historians of health and medicine have paid relatively little attention to this provision, tending to focus on the few that developed as acute general hospitals in the years after the 1929 Local Government Act – especially in and around London – while seeing those that didn’t as failures. In particular, some municipal authorities – like Sheffield – have been criticized for adopting the name hospital without broadening the range of acute services. Yet such an approach ignores the fact that the chronic, aged and infirm were a major part of those in need of institutional care yet meeting their needs still fell almost entirely on the local authority services.

The aim of this paper is to explore some of the ways in which services for the long term sick developed in the poor law and former poor law institutions of northern England in the second quarter of the twentieth century. Focusing on Leeds, Sheffield and Middlesbrough, it will examine the increasing classification of inmates/patients even before 1929; the development of specialties, especially during the Second World War; joint working with the voluntary sector in areas like cancer treatment; the use of follow-up and outpatient clinics; and the expansion and professionalization of medical and nursing staff. It was also show, however, that even the most ambitious authorities were locked into a cycle of bed-blocking, care over cure and residual services right up until 1948, in the main because someone had to look after these patients and the local state had acquired that role. Yet faced with this situation some authorities were expanding not just their acute services but also their non-acute medicine – especially where they had more than one institution – and this positive attitude to longer stay patients needs to be recognized for what is was and not be seen as a pale imitation of the voluntary sector.

Dr Anne-Marie McAlinden (School of Law, QUB) ‘Institutional Child Abuse in Ireland and Beyond: Public Inquiries, Truth Recovery and Restorative Justice

Public inquiries have been a front and centre political response to allegations of historic institutional child abuse in a number of jurisdictions including the Republic of Ireland and more recently Northern Ireland and Australia. This paper seeks to examine the use of the public inquiry model as a response to institutional child abuse in the Republic of Ireland and elsewhere. It will draw out the benefits as well as the limitations of public inquiries as mechanisms for providing truth recovery, and ‘justice’ for victims of historic abuse primarily in the form of giving victims a ‘voice’ in the proceedings and promoting offender and institutional accountability. Given the failures and criticisms of legalistic judge-led inquiries along these lines, the paper also seeks to examine the potential role of restorative justice in the aftermath of institutional child abuse. In particular it considers whether an appropriately modified public inquiry model with a restorative component might offer a more effective and viable means of moving on from the legacy of an abusive past.

Dr Leanne McCormick (University of Ulster) In Trouble’: Managing maternity cases in early C20th Belfast’

This paper will focus on unmarried mothers in Belfast in the early C20th in rescue and refuge homes. It will have a particular focus on the Salvation Army home in Belfast and will consider how unmarried mothers were treated within this institution and how their cases were managed. It will discuss how this management and attitudes towards unmarried mothers and illegitimacy changed over time. The wider context of illegitimacy and being pregnant outside wedlock will be considered and the limited options available for women who found themselves in this situation.

Dr Ian Miller (University of Ulster) “I Would Have Gone on with the Hunger Strike, but Force Feeding I could not Take”: Hunger Striking and Prison Welfare in English Prisons, c.1913-72

In 1913, the Prison Commissioners of England and Wales began to maintain a register of prison hunger strikes. They recorded motivations for hunger striking and how doctors dealt with food refusal. Between 1913 and 1940, 834 prisoners initiated hunger strikes. Collectively, they staged 1,188 hunger strikes. The overwhelming majority had no obvious political affiliation. Evidently, hunger striking maintained a notable presence in 20th-century prisons as a form of remonstration that disrupted disciplinary norms and challenged established power relations. Post-war journalism demonstrates that prisoners continued to refuse food throughout the century. This points to an important legacy left by the suffragettes and Irish republicans: their demonstration of the potency of food refusal as a strategy of prison rebellion.

Why did convict prisoners go on hunger strike? This paper maintains that the erosion of individual rights that was intrinsic to the disciplinary prison – starkly characterised by silence, solitude and discipline – created a milieu in which prison staff disregarded prisoner complaints and denied inmates the capacity to protest against institutional conditions. Decisions to protest were often predicated upon re-asserting individual rights in a setting that hinged upon conformity, reform and strict behavioural control. Many protested against poor diet and lack of access to healthcare (e.g. the provision of dentures or removal to hospital for an operation).

Yet the modern prison discouraged prisoner input into the conditions of incarceration. This paper demonstrates that medical staff typically resorted to force feeding rather than addressing prisoner concerns. Force feeding is most commonly associated with the suffragettes and, in Ireland, with Thomas Ashe. Nonetheless, force feeding remained in play as a coercive disciplinary technique. Between 1913 and 1940, the Commissioners recorded 7,734 force feedings. In the post-war period, newspapers published accounts of force feeding with rising frequency. As this paper demonstrates, the history of forcible feeding needs to be radically reassessed to account for the sustained use of feeding technologies on a plethora of convict prisoners.

Dr Katherine O’Donnell (University College Dublin) “I believe the women”: Justice for Magdalenes and Epistemic Injustice

In the second week of February 2013, Irish parliamentarians from all parties on the opposition benches stood to read testimony by former Magdalene women into the record of the parliament (Dáil). This testimony had been gathered (under ethical approval from University College Dublin) by the Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) campaign group and had been presented (and summarily ignored) by the Irish Government’s enquiry into State involvement in the Magdalene Institutions. The politicians read excerpts of the testimony which gave witness to the traumatic experiences of vulnerable girls and women being held under lock and key and forced to work at laundries run for profit by religious orders. As they concluded reading the horrific accounts to the Dáil chamber the parliamentarians declared: “I believe the women”. This was to be the final week of the long campaign conducted by Justice for Magdalenes for a State apology to the girls and women of the Magdalene Laundries. On February 19th 2013 the Prime Minister (Taoiseach) Enda Kenny gave a tearful apology to the former Magdalenes.

Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) comprised a group of five who pooled their academic and activist expertise to build what proved to be incontrovertible evidence of the Irish State’s involvement in the Magdalene Institutions, and from this base (of archival documents and oral histories) to make legal arguments which demonstrated how the Irish State had breached its own laws as well as the country’s constitution and in addition breaching international human rights treaties it had formally ratified. These legal arguments were to be found persuasive by the Irish Human Rights Commission (IHRC) and the United Nations Committee Against Torture (UNCAT).

This paper focuses on my initial motivations for joining JFM. I use Miranda Fricker’s Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (OUP 2007) to illustrate what I believe are the ethical obligations of academics to address the silence of shamed communities. I extend and modify Fricker’s theses in a number of ways and also draw on the work of Veena Das (e.g Violence and Descent into the Ordinary UCal Press, 2006) as I reflect on some of the ethical issues I encountered in working with JFM. The issues on which I will reflect include: the ethical tensions resulting from speaking on behalf of a group where I have not been mandated by that group; my skill set and academic training initially proved inadequate and I needed to undergo sharp learning curves with the worry that I would always prove unable for the tasks to hand; I could not claim a disinterested altruism as my academic thinking and career was benefiting from my involvement with JFM and I still have unresolved conflicts of duty and loyalty arising from my allegiance to and formation by Catholic education and upbringing.

Dr Olwen Purdue (Queen’s University Belfast) ‘A humiliating last resort? The role of the Union Workhouse in inter-war Belfast’

The Irish workhouse, established under the Irish Poor Law of 1838 and popularly regarded as a harsh and alien institution, was abolished in the Irish Free State within just a few years of its establishment. In Northern Ireland, by contrast, the poor law remained the body responsible for statutory welfare up until the introduction of the Welfare State in 1948. While rural unions saw a softening of the workhouse’s role in society, with a steady reduction in the number of workhouse inmates and the amalgamation and conversion of workhouses into district hospitals, this was far from the case in Belfast. The city’s poor law guardians remained committed to indoor relief as the default form of welfare available. As the economic crisis of the 1920s and 30s deepened and unemployment soared, Belfast workhouse remained the only option for thousands of the city’s poor, thus continuing its association with shame and despair and intensifying popular antagonism to it as an institution. This paper will explore the complex place of the workhouse in the context of inter-war Belfast both as an important provider of welfare and as the subject of social and political protest.

Dr John Welshman (University of Lancaster) ‘Wardens, letter writing, and the early Welfare State’

This paper surveys studies of Wardens in a range of settings and then focuses upon an archive of letters, running from the late 1940s to the early 1960s, that were written by one Warden and mothers following the stay of the latter in a residential institution, the Brentwood Recuperation Centre for Mothers and Children, which was located near Stockport, south of Manchester. Some historians have argued that smaller institutions were not necessarily more caring. However the themes that emerge from the letters examined here are those of friendship; advice and reassurance; information and news; material assistance; and advocacy. In contrast to work that has for too long concentrated on controlling practices and notions of shared stigma, the paper demonstrates that the regime of such residential institutions might not necessarily be unpleasant or punitive, and that the Warden, despite possessing only basic qualifications, could act as an important source of information, advice, and reassurance.

Participant Biographies

Dr Damien Brennan trained and worked as a psychiatric nurse in Dublin. He undertook his PhD at the Department of Sociology Trinity College Dublin, which detailed and critiqued mental hospital use in Ireland. He is Assistant Professor at the School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin where his teaching and research are focused on the Sociology of Health and Illness, particularly Mental Health. His recent publication Irish Insanity 1800-2000 (Routledge 2014), demonstrates that by the 1950’s the Republic of Ireland had the world’s highest rate of mental hospital residency. Dr Brennan proposes that there was no epidemic of mental illness in Ireland; rather asylum/mental hospital institutional confinement occurred in response to social forces.

Prof Barry Doyle is Professor of Health History in the University of Huddersfield. His research interests cover the medical, political, social and economic history of urban Britain in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His latest book is The Politics of Hospital Provision in Early Twentieth Century Britain (Studies for the Social History of Medicine: Pickering and Chatto London, 2014)

Dr Seán Lucey is an AHRC Research Fellow in Queen’s University Belfast. He has expertise in the history of welfare and social history of medicine in Ireland and Britain and is currently writing a book on public health in twentieth-century Belfast. He is the co-editor of Healthcare in Ireland and Britain 1850-1970: Voluntary, Regional and Comparative Perspectives (Institute of Historical Research, London, 2014). His other publications include The End of the Irish Poor Law?: Welfare and Healthcare Reform in Revolutionary and Independent Ireland (Manchester University Press, 2015).

Dr Anne-Marie McAlinden is a Reader in the School of Law at Queen’s with a primary degree in law and a Master’s and a PhD in Criminology and Criminal Justice. She has written widely on aspects of sexual offending concerning children, including institutional child abuse, ‘grooming’ and restorative justice. Her publications include two books, ‘The Shaming of Sexual Offenders’ (Hart Publishing, 2007) which was awarded the British Society of Criminology Book Prize 2008, and ‘”Grooming” and the Sexual Abuse of Children’ (OUP, 2012). She is currently principal investigator on an ESRC funded study on ‘Desistance from Sexual Offending,’

Dr Leanne McCormick is a Lecturer in Modern Irish Social History and Director of the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland at the University of Ulster. Leanne’s research interests include women’s history, history of sexuality and history of medicine in Ireland and more specifically twentieth century Northern Ireland. She has recently been working on abortion in twentieth century Northern Ireland and on Irish women in late C19th and early C20th New York. In 2010 she published Regulating Sexuality: Women in Twentieth Century Northern Ireland (MUP).

Dr Ian Miller is a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in Medical Humanities at the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland, University of Ulster. His current research focuses on the medical ethical issues that have surrounded hunger strike management (in Britain, Ireland and Northern Ireland) since 1909 when militant suffragettes were first force-fed. His publications include Reforming Food in Post-Famine Ireland: Medicine, Science and Improvement, 1845-1922 (Manchester University Press, 2014) and A Modern History of the Stomach: Gastric Illness, Medicine and British Society (Pickering and Chatto, 2011). He is the co-editor of Medicine, Health and Irish Experiences of Conflict, 1914-45 (Manchester University Press, 2015).

Dr Katherine O’Donnell lectures in feminist theory in University College Dublin (UCD). She is Director of UCD Women’s Studies Centre and is a member of Justice for Magdalenes Research which seeks to further develop research and educational materials on all matters relating to the Magdalene institutions in Ireland, particularly the fate of children born out of wedlock and their mothers.

Dr Olwen Purdue is a Lecturer in Irish Social and Economic History in Queen’s University Belfast. She is Co-Investigator of the AHRC ‘Welfare and Public Health in Belfast and the north of Ireland, c. 1800-1973’ project. Her current research focusses on questions of poverty and empowerment: in the ways in which the poor increasingly utilised the welfare system as part of their ‘economy of makeshifts’; in the ways in which the administration of the poor law became increasingly contested by social and economic elites and political movements.

Dr John Welshman’s research interests are at the interface of contemporary history, social policy, and public health. His current work falls into five main areas: the use of autobiographical material in the writing of history; the history of the debate over transmitted deprivation in the period 1972-82, and its links with current policy on child poverty and social exclusion; the history of the concepts of unemployability and worklessness; the history of tuberculosis, medical examination, and migration, in both the UK and Australia; and the history of care in the community since 1948, especially for people with learning disabilities. John’s publications include Underclass: A History of the Excluded since 1880 (Bloomsbury, 2013, 2nd ed.)

![Lady Gregory [from http://www.biography.com/people/lady-gregory-9320138]](http://www.belfastpovhist.com/files/2014/12/lady-gregory.jpg)