by Georgina Laragy

Teaching about pauper death and funerals today I went looking for an interesting alternative resource on YouTube for tomorrow’s seminar – videos of Victorian funerals, etc., but they were hard to find. However, I did come across a British Pathé video of Lady Gregory’s The Workhouse Ward which was performed by the Abbey Theatre Players and televised at some point in the 1950s. The play originally dates from the first decade of the twentieth century and relies much on the stage-Irishman motif for comedic effect. The production is broken into three ten minute videos/reels with the play beginning at 2.46 minutes after a ‘tourist advert’ for Ireland on reel one [instructions below on how to watch it]. Contained within the second reel/video is an interesting insight into the attitudes towards death in early 20th century Ireland, and amidst the comedy it hints at darker aspects of dying in the workhouse.

The production (though not the original play) opens with Mrs Donohoe heading off to the Cloone (fictional) workhouse. She means to remove her brother (Mike McInerney) who has been there many years. Mrs Donohoe’s husband has just died and she finds the house lonely. While she knew that it was ‘no credit to her to have her brother in the workhouse’, she had not gone to visit before. She was now cynically recognising the value of another man about the house to help with some of the work of the farm etc. Indeed, removing family from workhouses and asylums often occurred for those very purposes – to help with household chores.[1] Her husband had died ‘a fine natural death’ and ‘he got a lovely funeral; it would delight you to hear the priest reading the Mass’. Dying naturally, at home, and having a priest say the mass, was all emblematic of what has been referred to in the historiography as a ‘good death’, in contrast with death by violence or very sudden death.[2] Dying in his own home largely insured against a fate considered very gruesome at this time.If Donohoe had died in the workhouse then it is possible that the Anatomy Act of 1832 would have come into force; dying in an institution with a family that had no means to bury the body permitted the union authorities to sell the cadaver to medical schools for dissection. ‘Following the Anatomy Act, anatomists could claim bodies from workhouses and other public institutions, including voluntary hospitals.’[3] Mr Donohoe’s natural death at home offers a contrast to death in the workhouse, the likely fate for the two main characters in the play.

When we enter the eponymous ‘workhouse ward’ we hear Mike McInerney and Michael Miskell arguing, competing about who is in more pain, and the spectre of dissection is raised by McInerney. While Miskell shows the visible signs of gnarled hands and rheumatism as evidence of his infirmity and suffering, McInerney declares that his pain is internal; you would have ‘To open me, and to analyse me, …[to]… know what sort of a pain and a soreness I have in me heart and in me chest.’ Being ‘opened’ and ‘analysed’ was part of the dissection process to which paupers and criminals were subject. But we know that McInerney’s sister, Mrs Donohoe, is coming for him and such a fate is unlikely.

Before she arrives however, the competitive arguing continues, and the evidence becomes both somber and uniquely Irish, focusing on funerals past and the presence of the Banshee. Miskell declares that, ‘But for the wheat that was to be sowed, there would have been more sidecars and common cars at my father’s funeral, God rest his soul, than at any funeral ever left your own door.’ McInerney goes one step further, invoking a traditionally Irish figure; ‘And what do you say to the banshee? Isn’t she apt to have knowledge of the ancient race? Was ever she heard to screech or to cry for the Miskells? … She was not, but for the six families, the Hyneses, the Foxes, the Faheys, the Dooleys, the McInerneys. It is of the nature of the McInerneys she is I am thinking, crying for them the same as a king’s children.’ The Banshee was a mythical female figure believed to attend at the death of certain individuals and families, and as Nina Witoszek suggests was a means by which the dead ‘could still acquire social prestige’.[4] Respectability in the context of the Irish death was about the grandness of the funeral, the final fate of the dead body, and, in this ‘stage-Irish’ play, the relationship between the Banshee and the family. Such a family were akin to royalty!

While the banshee was a mythical creature, there were other very real concerns for the two workhouse paupers. Death in the workhouse even if it did not involve dissection, could involve burial in a pauper graveyard; anonymous and unmarked, the pauper grave was a sign of social failure. Despite his presence in the workhouse McInerney still believed he had some control over where he might be buried, ‘I … have one request only to be granted, and I leaving it in my will, it is what I would request, nine furrows of the field, nine ridges of the hills, nine waves of the ocean to be put between your grave and my own grave the time we will be laid in the ground! … I’d sooner than … know that my shadow and my ghost will not be knocking about with your shadow and your ghost, and the both of us waiting our time. I’d sooner be delayed in Purgatory!’ Miskell agrees, ‘Amen to that!’

These claims to control of their bodies post-mortem by McInerney and Miskell were not necessarily unfounded. Paupers might leave something to ensure burial in a graveyard, or a family member might come to claim their bodies. The Porter’s Book of the Thurles Poor Law Union reveals coffins going in and out of the workhouse, sometimes heavy with the remains of a pauper who had family with enough means, affection or pride, to ensure burial outside the workhouse grounds and beyond the pauper plot.

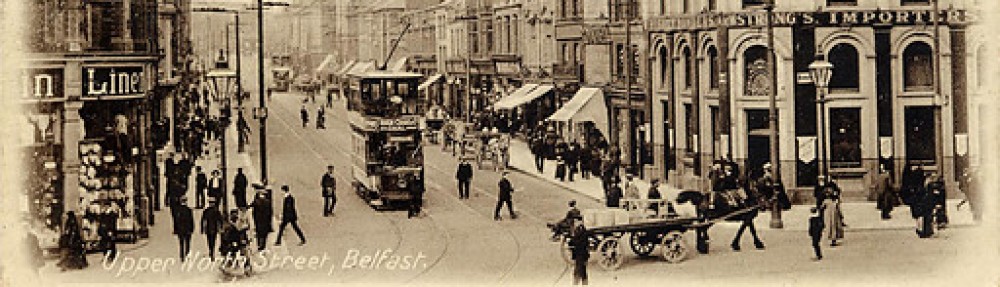

Click on the image above ‘The Workhouse Ward’ to watch the first reel. The second and third reels are here and here. I won’t give away the ending!

[1] Áine McCarthy, “Hearths, Bodies and Minds: Gender Ideology and Women’s Committal to Enniscorthy Lunatic Asylum, 1916 – 1925,” in Irish Women’s History, ed. Alan Hayes and Diane Urquhart, 115 – 136 (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2004).

[2] Clodagh Tait, Death, burial and commemoration in early modern Ireland, 1580-1650 (Palgrave, 2002), p. 7

[3] ‘Medicine and mutilation’, http://wellcomehistory.wordpress.com/2012/03/27/medicine-and-mutilation-oxford-manchester-and-the-impact-of-the-1832-anatomy-act/ [accessed 11 December 2014]

[4] Nina Witoszek, ‘Ireland: A Funerary Culture?’, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 76, No. 302 (Summer, 1987), p. 208. See also P. Lysaght, (1985) The banshee : a study in beliefs and legends about the Irish supernatural death-messenger (Dun Laoighre: Glendale)

![Lady Gregory [from http://www.biography.com/people/lady-gregory-9320138]](http://www.belfastpovhist.com/files/2014/12/lady-gregory.jpg)