by Stuart Irwin

‘One Sunday evening during the hour of the regular church services I walked from Royal Avenue to the Shankill Road. I was so struck by the large numbers of non-church going people that my heart was moved in a strange degree to reach them with the message of life’. (Rev. Henry Montgomery)

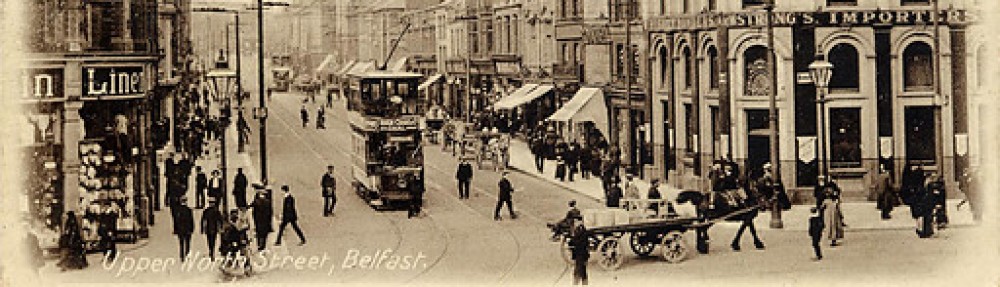

Belfast experienced remarkable urban growth across the nineteenth century. The population increased from 19,000 in 1801 to 350,000 by 1901. The main religious denominations responded accordingly to meet the increased need for provision, with Belfast experiencing a boom in church building during the late nineteenth century. In spite of such efforts, there remained many working-class people who had no connection with any church. Non-attendance at church was perceived as resulting in a growth of immoral behaviour, such as crime, excessive drinking, and gambling. The Witness, a Presbyterian newspaper in Belfast, offered a rather gloomy picture: ‘Abandoned by the religious, they soon learn to renounce religion itself; they become atheistic politicians, destructive anarchists, and are a menace to society and to civilization.’ Efforts were made by some concerned individuals to help those who were outside the church. One such example was the establishment of the Shankill Road Mission by the Revd Dr Henry Montgomery.

Henry Montgomery, a Presbyterian minister in the city, was committed to urban mission work and sought to offer Christian philanthropy to those who were beyond reach of the traditional church setting. In 1896 he decided to establish the Shankill Road Mission after visiting that working-class district of Belfast and being ‘so struck by the large numbers of non-church going people that my heart was moved in a strange degree to reach them with the message of life’. Montgomery set about securing private donations for the erection of multi-functional, all-purpose mission buildings on the Shankill Road, with original plans including a large semi-circular assembly hall, classrooms, medical facilities, a soup kitchen, retail units and a residential training department. Due to financial constraints, some of the more ambitious plans had to be shelved by the time the buildings were opened in November 1898.

These mission buildings provide a fascinating insight into Montgomery’s vision for the Shankill Road Mission and the values and ethos that guided his work. Previously, evangelical urban mission in the city had primarily been concerned with preaching the Gospel and saving the individual. In contrast, Montgomery wanted to promote individual conversion whilst also striving to deal with the material problems that people faced. On one occasion he stated that ‘[t]o preach religion without putting it into practice was not good anywhere, but it was unspeakably out of place when seeking to help the poor and needy.’ He envisioned the Mission as being a type of social centre, where all needs could be met.

The pioneering urban mission work that the Shankill Road Mission provided to the people of that area included the following: offering an extensive choice of activities, ranging from Gospel services and a Sunday school to a night school and music sessions; a Christmas supper for the poor and needy; and trips to the seaside to enjoy the fresh air.

The establishment of the Shankill Road Mission allowed Henry Montgomery to reach the non-churchgoing in a meaningful way by dealing ‘with a man as whole’. He was held in high esteem by the people of the Shankill Road area, as was reported in local newspapers following his death in February 1943.

‘Many people lined the streets in the area where Dr Montgomery had spent a long life of devoted service; blinds were drawn, doors of business premises were shut, and there were other evidences of the deep respect in which citizens, without distinction of creed, held the memory of the man who had long ministered to their spiritual and temporal needs.’

Stuart is a PhD student at the School of History and Anthropology at Queen’s University, Belfast. His Master’s thesis was on the subject of the Shankill Road Mission, and is he is pursuing the history of Belfast by looking at the ‘Belfast Corporation, 1880-1914: managing a mature industrial city’. To find out more please click here.