We have been quiet of late, getting stuck back into the archives and preparing for another academic year of exciting research and events on our project. There will be more blog posts and videos in the coming weeks, but until then here is a voice from the archives that caught my attention.

This letter home (possibly to Co. Down) seemed particularly fitting as students return to the lecture halls of Queen’s, and universities across Ireland and Britain. In November 1876, this first-year medical student was book-buying, dodging the rain in Belfast, and getting to grips with his dissection classes. The excitement of being in ‘town’ is well captured and although according to the ‘meta-data’ this young man sadly did not live to graduate, contemporaries would most likely have described him as an ‘interesting young man’; he was certainly interested in his studies, his friends and the new world in which he found himself.

Sydenham, Nov 18, 1876.[1]

My Dear Mama

I got a letter from [Annie] on Thursday night and a note from [Nora]. She says she has her eye full of nursing. [Tara] is knitting me a pair of stockings, has one done and is half through the other. I have a brush and comb which T. gave me …. I got the 9/6[2] book 2nd hand for 5/6 and the 24/- for 17/-. They are not the latest editions, yet they will do …. I was only in the dissecting room looking on. I be [sic] in it every day so that now I am quite used to it. My name is of course down for a part but as there are so many students before me I will not be dissecting for 3 or 4 weeks yet. … There were 2 very wet days when I took the [omni]bus. If you think I am too young if [Harry Trench] gets a shop, when my Session is done I could lie out a year and be with him and then like [Henderson] I could try the Druggist examinations in Dublin. It is just like a school you can leave when you like. Some when they have completed a year lie out a while and make some money and then return and complete their course. My 1st University examinations comes on in June, there is also one in September. Nearly every one goes in September. What I shall have to pass in will be French, Zoology, Botany and Physics … There was a great piece in Town yesterday the 27th Regiment embarked on a Steamer near Queen’s Bridge …. I have got into the way of working now and don’t care a hair for nobody.

I remain, your affectionate son, W.

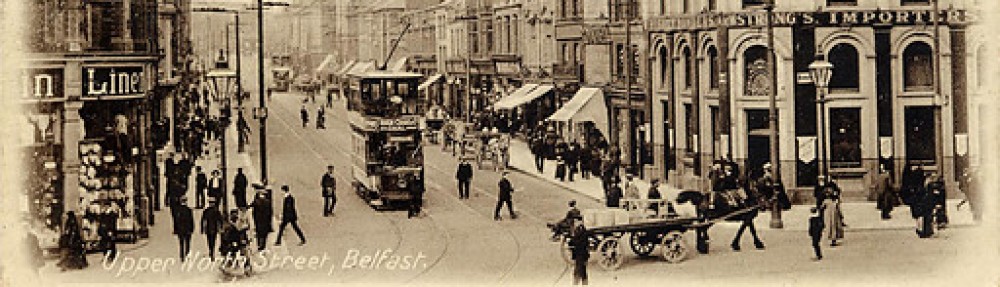

Click on the image above, which shows Medical Students ‘Rag Day’ in 1895, to be connected to the Medical School’s History Page.

[1] Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, D/953/3.

[2] 9 shillings and 6 pence would be worth approximately £22.95 in today’s money. See http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/ for calculations. I have only calculated the first amount for you.