If your ‘poor attempt at knitting’[1] was the only record you left on the pages of history how would we expand that historical window to find a broader view of your life? How to make you significant and meaningful, not just to you, and not only in the past; but for our understanding of that past? How could we demonstrate that as a poor knitter, you do have some genuine, albeit small, historical significance?

You left us no bonnets. There are no hole-riddled socks flattened in the pages of the book from 1905 in which I find you. You should not take this as indicative of how bad your knitting actually was; very few garments have survived into the twenty-first century, particularly those that might have clothed the poor. In the historical record, the words to describe you and your abilities are more prevalent than the wool you knitted, or the socks you yourself wore. The vision we have of your knitting is not based on the piece work itself, on that kind of primary evidence; rather the vision we have of you is conjured by the words typed out by Mrs Dickie in her report to the Local Government Board in Dublin. She had visited you, and your school-mates, on behalf of the Belfast Board of Guardians in July 1905. She was making sure you were doing well, making sure the Guardians’ and ratepayers’ money was not being wasted.

You were a ‘public child’, under the care of the state.[2] You were away from home, staying at St Mary’s Asylum for Female Blind in Dublin, because there was no one to take care of you, or at least no one who could take care of you and earn money to keep you at the same time. You were pressure on a struggling household and it is likely your parents placed you in the workhouse themselves so they could survive, one less non-working mouth to feed. That strategy meant you became a drain on the rates, and it was up to the state, through the Poor Law Guardians, to ensure that you would not be a drain on the rates for ever.

‘Woman Knitting’ by Otto Scholderer (1834-1902)

You appear in a single report, found in a volume of correspondence and taken largely out of context. But we can extrapolate a little from earlier documents found in this bound volume. It is clear from a previous report on boarded-out children made by the same Mrs Dickie that poor children created problems for government and local authorities. There are far more poor children in the historical record than middle-class or wealthy children. Swarms of disorderly, hungry, ‘street arabs’ could result in social chaos. They populate the records left behind by the clerks, inspectors, and relieving officers who worked for the Poor Law authorities.

What was to be done with these poor children? With you? How did the authorities ensure that the child, like the boots they wore, were not ‘allowed to become too much worn before being repaired’? That would be ‘extravagant in the long run’.[3] How did they ensure that the child not become indigent and lazy – pauperised essentially – before they could reach adulthood? The answer lay in industrial, technical or domestic training, and from a reasonably early age. “The greatest economy in the case of the pauper child is the expenditure upon him of whatever sum in reason is required to make him a healthy, useful member of society, fitted to earn a good living which will place him amongst the honest working classes, and for ever remove him and his family after him from being a perpetual burthen on the rates.”[4] This was not just about you, dear knitter, but about any children, grandchildren, you might have; subsequent generations would become free through your ability to knit! No pressure!

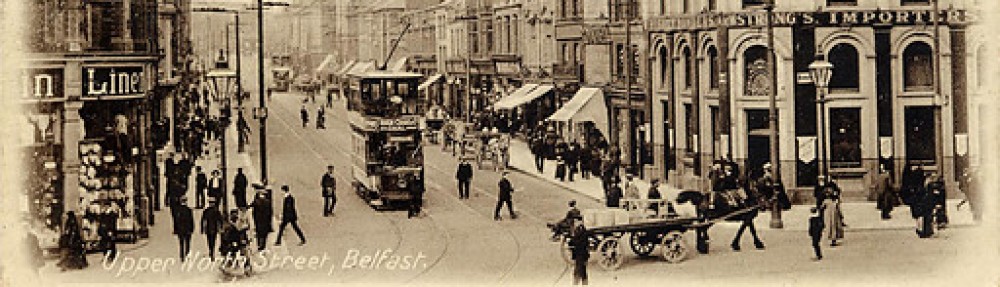

In the same school there were three other young girls who were being supported by the Belfast Guardians. You were the only ‘poor’ knitter, the rest were good. We know your name, and the names of all those Belfast girls who were in school in Dublin. But to preserve the anonymity of your identity, and to protect and respect those who may have come after you, we will not write it here. Your names are all entered in a report, bound in a volume of papers all dating from 1905, that likely travelled on the mail carriage of the train between Dublin and Belfast, between central and local government, between the Local Government Board in Dublin and the Poor Law Guardians in Belfast. It is likely your name travelled more than you did, Mrs Dickie made her reports every year after all.

You were twelve when she wrote her report in July 1905. And you were ‘growing stronger and advancing well in [your] lessons’. But your knitting was letting you down. Despite your academic improvement, Mrs Dickie and the guardians were very concerned for your knitting. This skill might have secured you employment; working on a contract providing army socks could provide you with a means of support.[5] But if you could not knit, then you had to find something else to do with your hands. Basket-weaving was a popular skill taught to children like you then. But we don’t know if you excelled at making baskets. We only know you were a poor knitter, upon which so much might depend!

And we only know this because an adult, a local government board inspector, typed it out on a page, posted her report to the Local Government Board, who forwarded it on to the Belfast Guardians, who subsequently preserved it in their administrative records. The knitting of a young blind girl was important in that early 20th century welfare regime for what it tells us about the poor, disability, welfare provision and institutionalisation, as well gendered training and employment opportunities.

P.S. I found you in the 1911 Census in the same school. You were 18 and still knitting, along with 149 others from around the country! Perhaps you improved!

[1] Report on Children in Extern Institutions supported by the Belfast Board of Guardians, Mrs Dickie; 15 July 1905 to Belfast BoG and Local Government Board, Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, BG/7/BC/35.

[2] Robbie Gilligan. “The “Public Child” and the Reluctant State?”, Eire / Ireland 44.1&2 (2009): 265-290

[3] Report on Boarding-Out Children by Mrs Dickie; 10 April 1905 to Belfast Board of Guardians, Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, BG/7/BC/35.

[5] Report on Children in Extern Institutions, 15 July 1905.