Commemorating Black Histories: Reflections on discovery within Queen’s University Belfast Library, Special Collections & Archives

Guest blog by Gift Sotonye-Frank and Dina Zoe Belluigi

As a contribution to Black History Month (BHM) 2024 by members of the African Scholars Research Network of Northern Ireland (AfSRN), we engaged the Library’s Special Collections and Archives for the purposes of generating discussion and commemorating mis/unrecognised or hidden histories, aligned with BHM UK’s theme of ‘Reclaiming narratives’.

Our original intention was to collect diverse discoveries for reflection, and from those, to organise the blog polyphonically – i.e. with distinct sections characterised by the disciplinary interests and styles of the different contributors. As you will read below, the dearth of relevant material reduced the available possibilities. However, two AfSRN members persevered, and chose to narrate their processes of discovery herein.

Discovering Nigerian resistance within the QUB Digital Special Collection: a focus on Ken Saro-Wiwa

Discovering the Special Collections

When I was first invited to contribute to a blog that referenced a selection from the McClay Library’s Special Collections, integrating my reflections on Black History Month, I was initially very excited. However, that excitement seemed to slowly turn to disappointment. This is because I assumed that following the Special Collections link would easily show a display on Black history resources. I searched the Collections A-Z, but the names of authors, places, and digital manuscripts did not resonate much with my interest in finding material on Black history.

Determined to make the best of the situation, I decided to look at previously posted Special Collections blogs. It was only then that my hope began to rise. I found myself agreeing with the words of Alberto Manguel that ‘The ideal library (like every library) holds at least one line that has been written exclusively for you.’

Since I was working remotely, I focused mostly on resources from the Digital Collection and Archives. As I researched into previous blog posts I looked at words that were hyperlinked. I found myself particularly interested in the links related to Black History. These links led me to several resources, including blogs on: The history of slavery, Decolonising the Curriculum, and History of Black Lives in the UK. However, one blog (Figure 1) that immediately resonated with me was about a touring exhibition that QUB hosted in 2022, of a collection on Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Figure 1: A screenshot of the QUB Library blog for Black History Month 2022.

Hope is rising: The collection on Ken Saro-Wiwa

Ken Saro-Wiwa (1941-1995) was a Nigerian writer and activist, who spoke out forcefully against the Nigerian military regime and the Anglo-Dutch petroleum company Royal Dutch/Shell, for causing environmental damage to the land of the Ogoni people in his native Rivers state.[i]

The blog describes how the special collection of Maynooth University on Ken Saro-Wiwa:

‘contains 28 letters to Sister Majella, 27 poems, recordings of visits and meetings with family and friends after Saro-Wiwa’s death, a collection of photographs, and other documents, including articles, reviews, flyers, and maps relating to Saro-Wiwa’s work and the cause of the Ogoni people, both in Nigeria and Ireland’.[ii]

From the moment I discovered Ken Saro-Wiwa’s collection, my hope continued to rise, and my disappointment gave way to fulfilment. The reason for my hope rising was due to my personal connection to this heroic figure. Growing up as a teenager, in Port Harcourt City, the capital city of Rivers State, I would listen and hear Ken Saro-Wiwa on television and on the radio speaking on issues and calling for the emancipation of the Ogoni people, which ultimately cost him his life. It was therefore a delight to see that a dedicated collection of his life and work can be found on this island, at Maynooth University Library. Finding this collection serves as a reminder of Ken Saro-Wiwa’s long-lasting legacy, which shaped and continues to shape the history of Nigeria, and in particular the history of the Ogoni people.

Black lives and the struggle to be free

In my view, the history of Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life and struggle bears a link to a form of slavery that relates to [T]he history of black lives in the United Kingdom and Ireland… built upon Britain’s colonial past, the history of slavery and the resettlement of communities’[iii]. Ken Saro-Wiwa’s history is not the one typically read about in the context of Black people, whom often are made to appear as nameless victims. This realization fuelled my curiosity to learn more about phenomenal black men and women who played significant roles in history.

In my search, I came across the often forgotten phenomenal Black British figures who helped to shape Britain, including the man, Olaudah Equiano. Olaudah Equiano, a Nigerian, was kidnapped at the age of 11 and sold into slavery. Olaudah Equiano’s 1789 autobiography titled ‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African’ also available through the McClay library, is a narration of his initial elite lifestyle as a free person, his journey to and out of slavery, and his later triumphs upon gaining his freedom. Equiano’s story, though centered around slavery, is an example of the so many black lives some unknown whose life and work, much like Ken Saro-Wiwa’s, highlight the struggles that are integral to Black history. For an insight into Equiano’s time in Belfast mobilising solidarity, see a 2020 BHM blog published by the Belfast Charitable Society.

On reflection, what I discovered about these historical figures and in light of the more recent experience of Ken Saro-Wiwa, serves as an important reminder that Black history is not monolithic. Rather, it encompasses a wide range of experiences, from the atrocities of slavery to the ongoing struggles for freedom and justice.

A trace of Black South African histories of resistence in the QUB Special Collections: A reproduced text by Steve Bantu Biko

By Prof Dina Zoe Belluigi, School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work

Approaching and exploring the Special Collections

I approached the Library’s resources as a South Africa intellectual who studies universities, the agency of academic citizens, and the politics of representation and of authorship in contexts with legacies of conflict and oppression.

Confirming assumptions about omissions within university archives, there were few immediate returns from online searches using the terms “Africa” or “South Africa” in the QUB Special Collections that I could find. The University Archives had one item: correspondence sent on the eve of the 20th Century from the British War Office to the then Queen’s College Belfast, requesting medical students serve in the South African war (QUB/1/5/1/10). Such material does not fall within the criteria of Black History Month, which seeks to centre, commemorate and raise discussion about Black histories particularly.[iv] This was quite surprising, since the University has had a number of significant figures within its staff with direct connections and influence on the continent – most notably, the prior President and Vice-Chancellor, and then Chancellor, of Queen’s University Belfast, Sir Eric Ashby who had a scholarly and professional interest in African universities.

A valued artefact within a donated collection

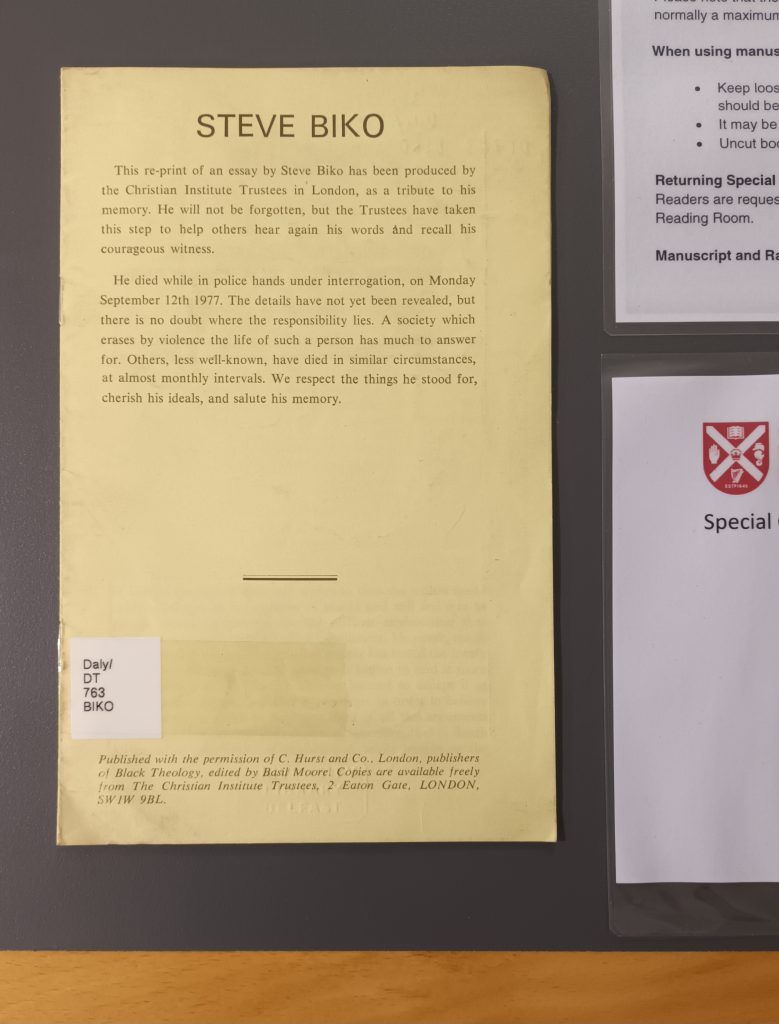

There was, however, a small treasure donated as a part of the book collection of Cahal Daly. It was the leaflet Black consciousness and the quest for true humanity, an essay written by Steve Bantu Biko, which has been described as providing “the moral framework for a future South Africa” with its notion that “something about being free people, liberated people, is inherent in us” (Barney Pityana in Accone, 2007, n.p.).[v] The pamphlet was published sometime after 1977 in London by Christian Institute Trustees (an open access version is here, published in 1978 by USA’s Ufahumo: The Journal of African studies). The front cover of the pamphlet, pictured in Figure 2, is explicit about the intention for its reproduction being “to help others hear again his words and recall his courageous witness”. It also recounts what could not be printed in South Africa at the time, about Biko’s murder.

Figure 2: Image of the front cover of the pamphlet on a desk in The Special Collections & Archives Reading Room at McClay Library (photograph by Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2024, Belfast).

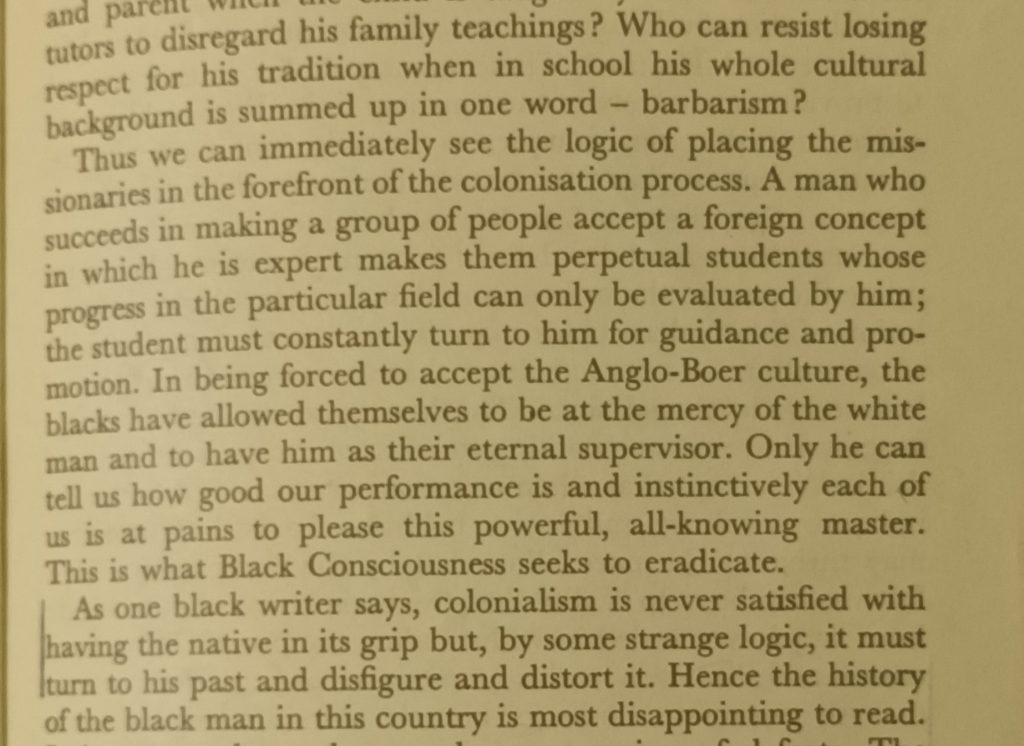

Within the text, Biko raised questions about the relation of oppression to thinking and various institutions of authority – including missionaries’ ab/use of education – which may have been how the pamphlet got into the Cardinal’s collection (a question worthy of further exploration). The photographed passage reverberates for those of us who aspire to be ‘educators’, and who study education:

Figure 3: Image of a part of page 16 of Dally’s donated copy of ‘Black consciousness and the quest for true humanity’ by Steve Bantu Biko (photograph by Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2024, Belfast).

The essay was finally (re)published in South Africa within a collection titled We write what we like: Celebrating Steve Biko forty years later.[vi] Its blurb evocatively states the spirit in which it was produced, as “a gift to a new generation which enjoys freedom, from one that was there when this freedom was being fought for. And it celebrates the man whose legacy is the freedom to think and say and write what we like on the 30th anniversary of his assassination.”

It is poignant that it was published by a university press. It is a collective commemoration of Biko’s most famous publication, I write what I like, developed from columns he wrote under the pseudonym of ‘Frank Talk’ for the South Africa Student Organisation’s (Saso) newsletter. Biko strongly advocated resistance through thought, arguing that “The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed” (Biko 1978)[vii], and affirming that “Black is beautiful”. At the time, as a banned person he was prohibited from publishing in South Africa, as was the citation of his name and work. Now, published scholarship by and about Biko and his legacy is accessible through the Library’s central collection (both analogue and digital); albeit the relation to struggles in Northern Ireland are not yet explicitly evident therein.

This month, to centre Black histories within one of my module’s curricula, students of Transforming Higher Education will be deliberating the struggles for (academic) freedom, the university as a route to intellectual authority, and consciousness. They will also engage with the short film, I walk where I like, inspired by a counter-narrative of a current Black South African academic.[viii]

I end with an excerpt taken from the Special Collection’s pamphlet because it relates directly to the politics of history writing, and the importance of Black authorship and reclamation.

‘… colonialism is never satisfied with having the native in its grip but, by some strange logic, it must turn to his past and disfigure and distort it…. Thus a lot of attention has to be paid to our history if we as blacks want to aid each other in our coming into consciousness. We have to rewrite out history and produce in it the heroes that formed the core of our resistance to the white invaders… we would be too naïve to expect our conquerors to write unbiased histories about us…’

(Biko, 197?, p.16-17)

About the contributors

Dr Sotonye-Frank is a law lecturer and the Equality Diversity and Inclusion Champion at Queen’s University Belfast School of Law. Her research focuses on girls’ rights to equality and non-discrimination in the areas of human rights, gender and education. For more on her academic practice, please visit https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/persons/gift-sotonye-frank-2

Prof Dina Zoe Belluigi is Professor of Authorship, Representation and Transformation in Academia, at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast. For more on her academic practice, please visit https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/persons/dina-belluigi

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Special Collections and Archive for their collaboration with AfSRN for the 2024 Black History Month commemorations.

For more about AfSRN, you are welcome to reach out to these contributors or to email AfScholars@qub.ac.uk.

[i] Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Movement-for-the-Survival-of-the-Ogoni-People accessed 3 September 2024.

[ii] Queen’s University Belfast Special Collection, ‘Ken Saro Wiwa Exhibition’, https://blogs.qub.ac.uk/specialcollections/ken-saro-wiwa-exhibition/ accessed 3 September 2024

[iii] Black History month 2020. Black history online: colonies, resettlement, identity

[iv] See Sinitiere (2016) for a collection on W. H. Du Bois’ arguments of the value such commemorations, and the role of university-based intellectuals and libraries, in Sinitiere, P. L. (2016, February 18). W. E. B. Du Bois and Black History Month [AAIHS]. Black Perspectives. https://www.aaihs.org/w-e-b-du-bois-and-black-history-month/

[v] Accone, D. (2007, July 5). The legacy of Steve Biko. The Mail & Guardian, n.p. https://mg.co.za/article/2007-07-06-the-legacy-of-steve-biko/ (accessed 17 July 2024)

[vi] Accone, D., Cindi, Z., Cooper, S., Innes, D., Jansen, J., Mafuna, B., Mangena, M., Mbeki, T., Mbele, V., Mbembe, A., Mda, L., Nefolovhodwe, P., Seleoane, M., Tsedu, M., & Wyk, C. (2007). We Write What We Like: Celebrating Steve Biko. Wits University Press. https://www.witspress.co.za/page/detail/We-Write-What-We-Like/?k=9781868147014#:~:text=We%20Write%20What%20We%20Like%20proudly%20echoes%20the%20title%20of,and%20write%20what%20we%20like.

[vii] Biko, S., & Stubbs, A. (1978). Steve Biko—I write what I like: A selection of his writings. Bowerdean Press. https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?context=L&vid=44QSUB_INST:QUB&search_scope=QUB_Campus&tab=QUB_Campus&docid=alma991003409659708046

[viii] Brent Meistre, 2020. I walk where I like. Video, 9 min 13 sec. Accessible at https://counternarrativefilm.wixsite.com/counter/i-walk-where-i-like-2

Very interesting read. Very well done Prof Dina Belluigi and Dr Gift Sotonye-Frank.👏🏽

Very well captured and captivating. I wanted to stop reading at the beginning, but something kept me reading to the last word – it was the simplicity of the writing and relatability.

Well done Gift & Dina. Great job 👏