“ ‘I’m forgetting what he looks like’, the boy says huskily… ‘Every day more pieces are gone. I’ll try and remember something and I won’t be able. It just gets worse and worse. And I can’t stop it’ … then, right in front of Howard, he punches himself in the head with his fists, hard as he is able, then again, and again, shouting over and over, ‘I can’t stop it! I can’t stop it!’ “

The image of any young person visibly breaking down and losing control is jarring in any context. In the context of Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies, what gives this scene in Ed’s Doghnut House its power and poignancy is the realisation the grief of the young man, the yawning absence of his best friend, allied with the trauma of having watched him collapse of an overdose, is the first set of circumstances which 14-year-old Ruprecht has been utterly unable to control in his own mind. Hitherto, the universe has been a series of logical conundrums, each more beautiful and fascinating than the last. String theory, M theory, the eleventh dimension each excites him in a way strange and foreign to his classmates. But what use is any theory that can’t account for how a person’s whole existence vanishes in an instant and which provides no route to restoring that existence.

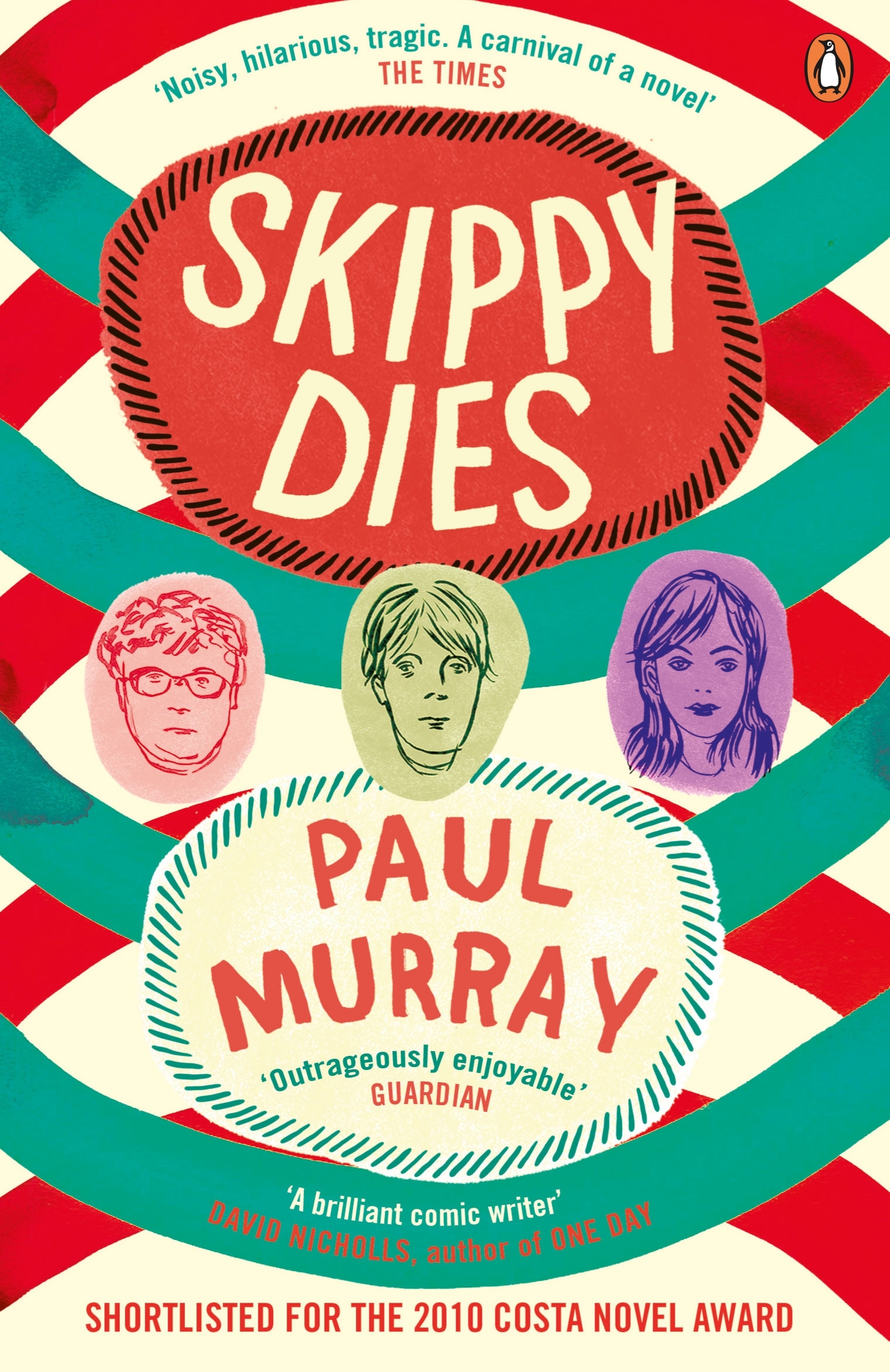

You might not expect to learn much as to the nature of death, grief and the challenge they pose to our ability to make sense of the world from a book described on its cover and most reviews as a triumph for comedic writing. But reading of Skippy Dies and speaking to author Paul Murray leave much to ponder on this and many other facets of our existence. The book shows us, slowly, humorously and forcibly, how the death of the young adolescent Daniel “Skippy” Juster comes to affect a great many lives, young and old. We see this simultaneously through individuals and through groups whose collective flailing and failing attempts at grieving loss and restoring normality steer us to an important conclusion: how a person sets about making sense of such a profound event as death speaks to the whole of the culture they inhabit.

Murray contends that death is unique in exposing most fully how deficient our view of the world can be. “All of the characters subscribe to some universal explanation of how the world is. Skippy has his computer game; Howard (the boys’ history teacher) has his studies of the First World War; and Ruprecht, most obviously, has M Theory. These are all ideas which the person thinks holds the key to understanding everything. My suspicion is that, ultimately, any objective system of understanding the world will be no use to you as a subjective being.” Behind his loss of composure and outbreak of fury in Ed’s Doghnut House, Ruprecht is not just mourning a person, but saying a bitter farewell to a scheme and a logic which not only has served him as a tool, but has allowed him to form a convincing persona and self-definition.

Of course, not every character falls apart so swiftly and completely. “I didn’t want everyone to have this instant epiphany and become this profound and introspective person just because of this experience. It doesn’t happen like that.” Skippy’s femme fatale, Lori, the recipient of a declaration of love which becomes Skippy’s last earthly act, is cast into the spotlight of the media by the Tragic Event. This is the same spotlight she and her parents have desired for her to be under since she began to blossom and set her sights on TV modelling. Before she knows it there is talk of screen tests.

“Dad sits back and rests his hands behind his head. Something good may yet come of all this, he says contentedly. And you deserve it too, after all you’ve been through.”

“W.H. Auden has a quote about how every artist is craving tragedy in their lives. I think when something tragic happens us, we do tend to milk it a bit. We’re all looking for this little badge of authenticity to make us seem more real. In Lori’s case, grief becomes a kind of social capital and that’s what she uses it for. I don’t think she realises the way that it’s hit her until later on.”

Among Skippy’s friends, rifts appear very quickly as each takes the loss differently. Frustrated by his denial and persistence with science as the solution, Dennis Hoey takes to yelling the word “dead” repeatedly into the face of Ruprecht, even adopting the tune of La Marsaeillaise (“Dead-dead-dead-dead-de-de-dead-dead-dead”), until a flurry of punches arrives his way. As a group, each starts to retreat away.

“It’s as if Skippy has been one of those insignificant-looking pins that it turns out holds the whole machine together.”

The school year is also affected, at first with a silent resolve to say nothing and say nothing about saying nothing, later developing into a collective unrest over rumours surrounding the circumstances of the death. Here, Murray reaches for one of sociology’s big concepts, as the acting principle looks on at the second years’ growing anomie. “If you go to a school like the school in the book, the ethos is that these people know the score, know how the world works and if you’re a smart person, you’ll fall in with this. If you’re a good boy and follow the rules, then you don’t really have anything to worry about, you’ll go up the ladder and you’ll end up at the top. That’s a fiction, a lie and a death is one thing you can’t lie you’re way around. What the kids are realising in the book is that here is something that school isn’t able to fix and whether they cover up the reasons or give them explanations, they can’t change what’s happened.”

And so, to Howard, the school’s not-altogether-secret shame: a failed finance guy returned to the school to a non-vocation of teaching history. Early in the book, he accounts for his involuntary retirement from trading futures in London with the succinct line “Don’t you read the papers? Not enough futures to go around”, essentially the antithesis of the Seabrook College motto. Through a combination of accident and escapism, Howard comes to spend the period of the book becoming steadily engrossed in the First World War, from which he draws endless parallels. The most fruitful vein is that of betrayal, between generations and within families. Promised jobs and opportunities on departure, the surviving soldiers arrived home to find those promises every bit as broken as their lives and bodies, left instead with little but memories of seeing mates cut down in the trenches. Betrayal and lies are all he sees in Seabrook.

In the moments preceding Ruprecht’s visible dissolution in Ed’s Doughnut House, Howard has been responding to the boy’s queries about séance and communication with the dead, a theme he has mentioned in class. He has sketched the involvement of some famous characters, Arthur Conan Doyle and Oliver Lodge, in the movement to advance the technology of séance. Both had lost sons in the War. “This was a world that had literally gone crazy with grief”, Howard explains “At the same time, it was an age when science and technology promised they could deliver all the answers. Suddenly you could talk to somebody on the other side of the world. Why shouldn’t you be able to talk to the dead?” Was it Murray’s intention to juxtaposition science and history beside one another? “I had a chance meeting with an old friend who was researching how the First World War was mourned. When I started to read up on it, I saw that the context of the Victorian era was a lot like our own, in that it was quite materialistic and science and technology seemed to be on the cusp of explaining everything, to the point where people thought God and death could be explained through science. So here’s another example of a society who had it all sussed out and then this huge wrecking ball comes along. The society didn’t have the wherewithal to bring them through this, so we see this astonishing psychic breakdown. One in five people had lost a family member. It was like a boot through the window.”

Losing friends is thought to be the preserve of one’s older years, yet the experience seems all the more salient when mixed into the already tumultuous experience of adolescence. Here, Murray recalls a recent interview in which philosopher Simon Critchley discusses the relationship of youth with death. “Critchley’s point was that when you’re a teenager you think of death solely in terms of yourself. You think, I’m not afraid of dying, I don’t mind doing dangerous things because I don’t feel death is any real threat. But what comes to you much later is that the real significance of death and loss is losing other people. So if you’re still in your teens and someone else is taken out of your life, it seems inconceivable”.

I wondered to what extent Murray drew on personal bereavement to write about its effects on his characters. “In my own experience of grief, it takes a while. It’s like a little black hole that you can’t see but its gravity is pulling everything towards it. It feels like you’re the same person you always were and then you notice you’re acting in very strange ways.” As to whether he draws directly on losing a school friend, he insists this book is fiction. “I did lose a friend in college, which was a really difficult experience. Someone in my brother’s year committed suicide. It feels like it’s sort of in the air, as suicide has become such a problem.” Given that, was it difficult to base a humorous book around such a grave event? “I wrote the book linearly, so just as you read about the death at the start, that was my starting point. There’s a lot of comedy in the book, but sometimes people in oppressive environments use humour to get through difficult situations, so I found it good to work across those different registers.”

The only good reason to put this book down is to laugh, which I often needed to. Yet, for all the relentless and beautifully crafted lines of hilarity, it would be hard to come by such a thorough treatise on some of life’s most grave and serious points, and how seriously we need to consider our limitations as a thinking society. Our grief may often seem like a personal journey, but our capacity to grieve may be a marker of our strength or weakness as a community or society.