Marie Sallé seminar

Mistriss SALLÉ toujours errante,

Et toujours vivant mécontente …

Mistress Sallé, forever wandering and forever discontented …

Shortly after Marie Sallé’s return to Paris in the summer of 1735, at the end of what turned out to be her last season in London, the Abbé Prévost’s journal, Le Pour et Contre, gave an account of an incident at Covent Garden that would certainly have explained her reason for leaving London in a state of discontent. This incident had supposedly occurred during a performance of the ballet scenes in Handel’s new opera Alcina, choreographed by Sallé herself:

People unashamedly hissed her [onstage] in the theatre. The opera Alcina was being performed. Mademoiselle Sallé had composed a Ballet, in which she took the role of Cupid, a role she danced in male attire. It is said that this attire ill-suits her and was apparently the cause of her fall from grace. [Emphasis added.]

On n’a pas eu honte de la siffler en plein théâtre. On jouait l’Opéra d’Alcine. Mademoiselle Sallé avait composé un Ballet, dans lequel elle se chargea du rôle de Cupidon, qu’elle entreprit de danser en habit d’homme. Cet habit, dit- on, lui sied mal, et fut apparemment la cause de sa disgrâce.1)

These events are widely assumed to have taken place at the première of Alcina on 16 April 1735; indeed, the Biographical Dictionary of Actors, following Prévost, states as a fact that on that date she was hissed by members of the rival opera company from the King’s theatre.2)

A pirated edition of Le Pour et Contre in the Hague had already published a different report of her dissatisfaction with England, followed by an epigram, two lines of which appear above as my epigraph: “Mademoiselle Sallé, unable to appear in England with the same satisfaction as before, when she received the applause of the Court and the City, has resolved to abandon the English and return to France. I am told that she has indeed left and is expected to arrive in Paris at any moment. Here is an Epigram on the subject of her return:

EPIGRAM on the Return of Mademoiselle Sallé

Mlle SALLÉ forever wandering,

And living forever discontented,

Still deafened by the sound of hissing,

Heavy of heart, light of purse,

Comes home, cursing the English,

Just as, on leaving for England,

She had cursed the French.

Mademoiselle Sallé ne pouvant plus paraitre en Angleterre avec la même satisfaction que ci-devant, lorsqu’elle recueillait les applaudissements de la Cour et de la Ville, a résolu d’abandonner les Anglais et de retourner en France. On me mande qu’elle est effectivement partie, et qu’on l’attend à Paris à tout moment. Voici une Epigramme qu’on a faite sur son retour.

EPIGRAMME sur le retour de Mademoiselle Sallé

Mistriss SALLÉ toujours errante,

Et toujours vivant mécontente,

Sourde encor du bruit des sifflets,

Le cœur gros, la bourse légère,

Revient, maudissant les Anglais,

Comme en partant pour l’Angleterre

Elle maudissait les Français.3)

This news item must have been written around mid-June (NS) because on 2 July 1735 (NS) in Paris, les nouvelles à la main [manuscript news-sheets] carried a report which appears to show knowledge of this pirated Hague edition of Le Pour et contre:

La Sallé has come back from England, as discontented with the English as she was with us when she left. Here is an epigram that depicts her perfectly …

La Sallé est revenue d’Angleterre, aussi mécontente des Anglais qu’elle l’était de nous quand elle partit. Voici une épigramme qui la peint au naturel …

The news-sheet reproduces the epigram with a slightly different second line: ‘Et qui vit toujours mécontente’ [‘And who lives forever discontented’].4) According to Prévost’s account, the hissing incident strongly suggested that Sallé, once the idol of London society, had fallen out of favour with it. This situation had been foreshadowed by other observers. In a letter of 9 January 1734 Mattieu Marais noted:

The English, who know little about dance, are growing tired of Sallé and say they had enough of her last year, and the ladies find her prissy [pimpesouée] and hoity-toity.

Les Anglais, qui se connaissent peu en danse, se lassent de la Sallé et disent qu’ils en ont eu assez il y a un an, et les dames anglaises la trouvent pimpe-souée et faisant la milady.5)

The word ‘pimpesouée’ implies a woman who plays ‘hard to get’ and it may be that Sallé’s impeccable private life was partly responsible for the ladies’ resentment of a mere dancer whose moral standards were higher than their own. In early 1735, Prévost had printed some English verses indicating that Sallé had aroused displeasure not only for her financial success but, more dangerously, for expressing a low opinion of the English:

Miss Sallé too (late come from France)

Says we can neither dress nor dance.

Yet she, as is agreed by most,

Dresses and dances at our cost.

She from experience draws her rules

And justly calls the English fools.

For such they are, since none but such

For foreign Jilts would pay so much.6)

In the following I propose to re-examine the supposed Cupid incident and suggest an alternative explanation for what happened.

First, it is important to note that, other than in Prévost (whose wording –‘it is said’ and ‘apparently’—indicates that he is writing at second or third hand), there is no reference to the Cupid incident in any other source. It is nowhere mentioned in the London press or in any contemporary French or English correspondence – including that of John Rich and the inveterate gossip Lord Hervey, who would surely have commented on it. As for the suggestion that the hissing on this occasion came from a rival company, Sallé seems to have been on good terms with dancers from the other theatres; in fact, the London Daily Post and General Advertiser had reported on 17 March 1735 that

The Celebrated Monsieur [George] Denoyer and Mademoiselle Salle, by Permission of the Masters of the two Theatres Royal, … agreed to dance together at each other’s Benefit.

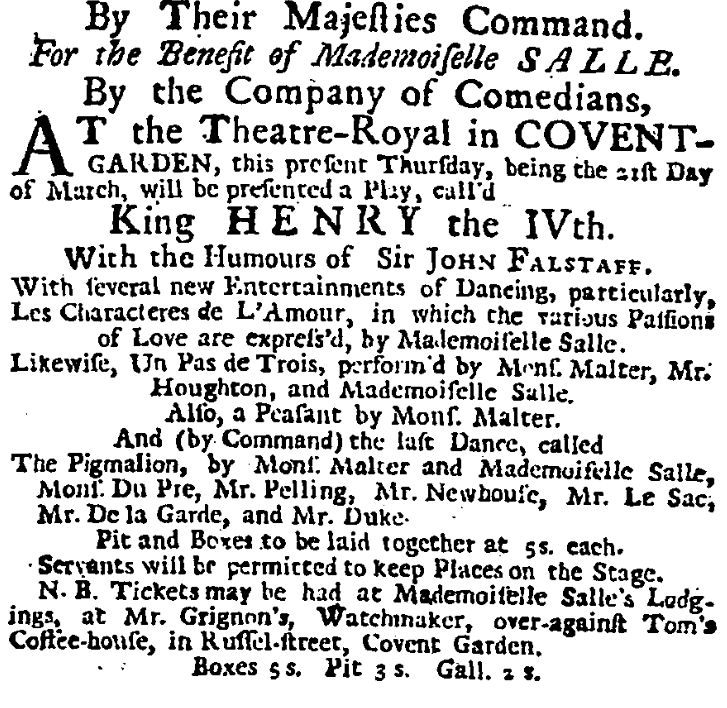

The idea that hissing could have been provoked by Sallé’s costume as one of the fluttering cupids in Alcina’s garden is, in my view, equally far-fetched. In the London seasons of 1733-4 and 1734-5, travesty roles for women in dance, often as cupids or petits-maîtres, were commonplace, as can be seen from these selections from two seasons’ playbills in The London Stage.

Covent Garden, 16 March 1734. The Nuptial Masque or The Triumphs of Cupid and Hymen. ‘Cupid – Miss Norsa, the first time of her appearing in boy’s clothes.’

Drury Lane, 18 March 1734. ‘Minuet by Mlle Grognet (in Boy’s Cloaths);’ Prince of Wales present.

Covent Garden, 18 March 1734. ‘A Courtier by Miss Norsa in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Goodman’s Fields, 25 March 1734. ‘An Epilogue of thanks spoke by Mrs Roberts in Man’s Cloaths.’

Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1 April 1734. ‘Minuet by Mlle Grognet in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Covent Garden, 6 April 1734. ‘Mrs Kilby, the first time of her appearing in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Covent Garden, 29 April 1735 ‘Harlequin by Miss Norsa Jr., the first time of her appearance on any stage.’

Haymarket, 5 May 1735. Grognet benefit. ‘The Wedding (new) by Mlle Mimi Verneuil and Mlle Grognet in Man’s Clothes.

Covent Garden, 20 May 1735. ‘Afterpiece Minuet by Mlle Grognet in Men’s Cloths, and Miss Baston.’

York Buildings, 3 June 1735. ‘A Minuet by Miss Norsa in Boy’s Cloaths and Miss Oates.’

Haymarket, 9 July 1735. Aaron Hill Zara. Epilogue spoken ‘by Miss ___ in Boy’s Cloaths.’

Click here for an image of the actress Peg Woffington in a trousers role (London, 1746).

However, in dance (as opposed to opera) this kind of travesty was almost exclusively the preserve of very young girls and women.7) It was, for example, a specialty of Manon Grognet (‘la petite grognette’ as Mathieu Marais called her in 1733), who was currently dancing in travesty as a petit-maître at the Little Haymarket Theatre – but, as Marais had written, specifically contrasting her dancing with that of Sallé, ‘it’s a different kind of dancing, and there will be enough for everyone [c’est une autre danse, et il y en aura pour tout le monde].’8) What he was surely referring to was the difference between the ‘belle danse’ of the Opéra-trained Sallé and the sprightly commedia style that Grognet would have learned at the fairs.) As an adult, Sallé (aged twenty-six in 1735) never danced in male attire, and nothing in her entire adult career in London or Paris lends a shred of credibility to the idea that this woman of impeccable taste and judgment would have played a young male Cupid, so soon after the refined grandeur of her recent ground-breaking appearances as Galatea in Pygmalion, Ariadne in Bacchus and Ariadne, a Bridal Virgin in Apollo and Daphne, and the Bridal Nymph in A Nuptial Masque.

How, then, did this unlikely story arise? I believe there may be a clue in a letter from Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, to Diana, Duchess of Bedford, dated 24 June 1735, telling of an incident which did indeed take place at Covent Garden during a performance of Alcina. The King attended performances of this opera both on the opening night, 16 April, and on 14 May with the Queen and Princess Amelia. Since nothing unseemly was reported about the opening night (it surely would have been publicly noticed then), the incident recounted by the Duchess must have taken place on 14 May. While the Duchess could not be bothered to know the name of the performer in question, Sarah McCleave has identified her as Marie Sallé:

The famous dancing woman (I do not know her name) in the opera, the audience were so excessive fond of her that they hollered out “encore” several times to have her dance over again, which she could not do, because as she was coming on again, the King made a motion with his hand that she should not. At last the dispute was so violent that to put an end to it, the curtain was let down, whereby the spectators lost all after the third act.9)

The Duchess’s letter provides evidence not only that Sallé danced in Alcina until 14 May but, more importantly, that a full month after the première of the opera, far from being out of favour, Sallé was still immensely popular. As Alcina has only three acts, the Duchess’s meaning is unclear, but it seems likely that the incident took place at the end of the second act in the ballet of good and bad dreams, probably the ‘Entrance of pleasant dreams’ [Entrée des songes agréables], which Handel borrowed from the ballet he had written for Sallé in Ariodante in January 1735. The King’s gesture was clearly one of impatience, indicating that he wanted the evening to end soon. On the following day, 15 May, he was to prorogue parliament and on 17 May he would eagerly set out for Hanover and the arms of his mistress. He had sat through two acts and his mind was already elsewhere.

As the Duchess makes clear, the audience’s anger at the King’s peremptory dismissal of the popular dancer was so violent that the performance had to be brought to an end. Hissing there certainly was, and Sallé was indeed obliged to leave the stage, not because of her costume (which audiences over the three previous weeks had already seen without comment), but, according to the Duchess of Marlborough, in obedience to a gesture from the King which most of the audience would not have seen. Could it be that the noisy outburst at this aborted performance on 14 May was thought by some (especially those who heard of it at second-hand) to have been directed not against the King but against Sallé herself when she attempted to return to the stage to take her encore? Might it even be that her entrée was not a solo and that a cupid or cupids en travesti entered with her, adding to the confusion?

This explanation may perhaps be supported by the opening of the already quoted news item from the pirated Hague edition of Le Pour et contre:

Parisians have learned with a joy that is neither shocking nor insulting to Mademoiselle Sallé, of the unfortunate accident[10] that befell her recently [emphasis added] in London, since this insult seemed to them to predict the prompt return of this famous dancer.

Les Parisiens ont appris avec une joie qui n’a rien de choquant ni d’insultant pour Mademoiselle Sallé, le fâcheux accident qui lui est arrivé en dernier lieu [emphasis added] à Londres, puisque cet affront leur semblait pronostiquer le prompt retour de cette fameuse Danseuse.

This report seems to me entirely consistent with the incident described by the Duchess of Marlborough. The report that Sallé was being less favourably received than before by the Court (the King?) and the City (the raucous audience?), makes the ‘unfortunate incident’ sound very recent, far more like the ‘violent dispute’ which happened on 14 May than something which has hitherto been presumed to have taken place on 16 April and of which there is not a single mention in the English press.

Since the Earl of Egmont, a friend and confident of both King and Queen, noted in his journal for 14 May, ‘In the evening I went to Handel’s opera called Alcina’, it might seem odd that he made no mention of any disturbance. However, earlier in the day, he had had a long discussion with the Bishop of Salisbury concerning the unstable state of international affairs, and the King’s apparent indifference to it. The Bishop warned Egmont that ‘Sir Robert [Walpole] sees his situation and is very uneasy at it, and so is the Queen. […] It is a great misfortune the King is made believe the people’s affections are warm to him, none daring to tell him the truth.’11) Egmont might, then, have found nothing newsworthy in a rowdy demonstration against the monarch and in favour of a much-loved dancer.

Sallé, however, may well have interpreted the King’s gesture as an unexpected sign of sudden royal disfavour, and she might even have taken the ensuing raucous demonstration to be directed against her rather than against the King. After the performance on 14 May there is not a single known mention of her by name in the London press or contemporary correspondence concerning the remainder of the Covent Garden season. There were altogether eighteen performances of Alcina, ending with a royal command performance for Queen Caroline on 2 July, but Sallé cannot have been dancing in London on 2 July 1735, or at any point after mid-June at the latest, for one very simple reason. What seems to have been hitherto overlooked is the crucial fact that Britain did not adopt the Gregorian revisions to the calendar until 1752, and until then the date in England (Old Style) was eleven days behind the date in Catholic Europe (New Style). Sallé must have already been in Paris well before 2 July (New Style) for the news of her arrival to reach the news-sheets and inspire the mocking epigram. The journey from London to Paris could take over a week, often ten days or more, depending on the state of the seas and the roads. This means that at the very latest Sallé must have left London around mid-June (OS) and performances of Alcina must therefore have continued without her.12) It could even be that Sallé walked out of Covent Garden immediately after the ‘unfortunate incident’ of 14 May; her ‘empty purse’ mentioned in the mocking verses would be the result of the loss of salary for the remaining nine performances. This view is supported by the fact that, when Alcina was revived, in November of the 1736-7 season, it was without either Sallé or the dances.

Sallé’s behaviour may seem an over-reaction to what might best be described as an unfortunate concatenation of misunderstandings. But it was in keeping with her hypersensitive and headstrong character. There has been no previous discussion of the fact that every one of Sallé’s seasons between 1730 and 1735 ended abruptly in some kind of irregular incident, violent altercation, and/or illness — Paris in August 1730; London in May-June 1731; Paris in November-December 1732; London in May 1734; London in May-June 1735. The nouvelles à la main dated 25 August 1730 reported that she and one of the directors (Claude-François Leboeuf) had argued on the stage of the Opéra, perhaps even coming to blows.13) In London, where she remained from November to the end of the 1730-31 season, Sallé received a glittering royal benefit on 25 March 1731. However, her name disappeared from the playbills from 3 May until 1 June, when there was a single announcement of ‘Dancing by Mlle Sallé’; then Rich’s company moved to Richmond, and Sallé, presumably, went back to France. No explanation seems to exist for this rather odd, month-long hiatus. In her letter to the Duchess of Richmond in 1731, Sallé made it abundantly clear that she did not like John Rich, whom she described as ‘a rude and unjust man at whose hands I have suffered too much ill treatment [un homme impoli et injuste, dont j’ai souffert trop de mauvais traitemens].’14) The last two lines of the epigram written about her two years later – ‘Just as on leaving for England/ She had cursed the French’ — would seem to be further confirmation of the fact that Sallé had left Paris in October 1733 in unpleasant circumstances. On 24 May 1734, Pygmalion and Bacchus and Ariadne were advertised, as ‘being the last Time of the Company’s performing this Season‘ (Daily Journal). However, according to Rich’s Register the audience was dismissed, ‘by reason Madem Sallé wou’d not come to the House.’15)

Whatever exactly happened in 1735, it is clear that the ‘unhappy incident’ (‘fâcheux accident’) was the culmination of a number of unfortunate events, and one from which she did not recover. It affected her health: Voltaire, who saw her soon after her return, wrote on 15 July to Sallé’s ardent but frustrated admirer, Nicolas-Claude Thiériot, ‘So, you are avenged; your nymph has lost her beauty [Vous voilà donc vengé de votre nymphe; elle a perdu sa beauté].’16) Sallé had not, however, lost the admiration of audiences in both countries. The pirated Pour et contre had recorded the ‘joy’ with which Parisians looked forward to her return:

It is not yet known whether she will dance at the Opéra, and the public display an impatience about this which does her credit.

On ne sait encore si elle dansera à l’Opéra,et le public témoigne là-dessus une impatience qui lui fait honneur.

The Daily Journal of Tuesday 5 August (OS) reported that, to the delight of all Paris, Sallé was to dance in the new opera Les Victoires Galantes, the original title of Fuzelier-Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes, premiered on 23 August 1735 (NS). It added,

We do not mind what shall be done upon the Rhine by Marshall Coigny, or in Lombardy by Marshall Noailles, but what Mademoiselle Sallé will perform on the stage of Paris.17)

The fact that her activities were the object of so much speculation may simply be the result of her ‘celebrity’ status, enhanced by prurient interest in the ‘virtue’ (i.e., chastity) of a mere dancer and perhaps also by the very unpredictability that I have been describing. Judges as severe as Voltaire seem to have been charmed by her charismatic personality. Proof that she still had a loyal following in London is suggested by the report in the Grub Street Journal for 19 August 1736 that Desnoyer, ‘the famous Dancer at Drury-lane theatre,’ had gone to Paris ‘by order of Mr. Fleetwood [the theatre manager]’ to try to hire Sallé for the winter season – something that certainly does not suggest any dimming of her star. But the hopes of Desnoyer and Fleetwood were to be disappointed.

Did Sallé ever return to England? Dacier notes that some of her contemporaries thought this, though he could find no evidence of it.18) An unsubstantiated and uncorroborated account, written some ten years after the event it claims to describe, was included in an anonymous article (Mémoires d’un Musicien) which appeared in three numbers of the Journal Encyclopédique in May-June 1756, just a month before Sallé’s death in obscurity:

Mlle Sallé, the French dancer in whom the most respectable morals were united with the rarest talents, caused admiration on the London stage for graceful qualities which the English had not hitherto seen, and which are created and acquired only in France. I had known her there; she seemed most content to receive me, and I was witness to her unhesitating sacrifice of over a thousand louis which ought to have accrued from her engagement with Handel, even though she was solicited by the greatest lords in London to break it off, which a caprice led them to speculate would be more desirable.

Mlle. Sallé, Danseuse Françoise, qui scavoit unir les moeurs les plus respectables aux plus rares talens, faisoit assez admirer sur le Théâtre de Londres des graces que les Anglois n’avoient pas encore connues, & qui ne naissent, & ne peuvent s’acquerir qu’en France. Je l’y avois connue, elle parut fort aise de me voir, & je fus temoin du sacrifice qu’elle n’hésita point de faire de plus de mille Louis qui auroient dû lui revenir de son engagement avec Hendel, quoique sollicité par les plus grands Seigneurs de Londre de le rompre, pour en prendre un nouveau avec un entrepreneur qu’un caprice leur faisoit esperer plus agréable.19)

In a 1996 article by David Charlton and Sarah Hibberd, these few lines became the subject of scholarly speculation on the possibility of Sallé’s return to London, a discussion taken up and amplified by Sarah McCleave.20) Whatever the facts of this matter may be, one thing is clear: after leaving London in June 1735, Marie Sallé was never again to dance on the English stage.

Dr Robert V Kenny is Honorary Fellow in French Studies in the University of Leicester. His full-length study of Sallé’s uncle François Moylin (Francisque) and his travelling theatre companies in England and France will be published by Boydell and Brewer early in 2025.

The next post will be a report on an aspect of Sarah McCleave’s ‘Fame and the Female Dancer’ project.

Marie Sallé (1709-1756) was an acclaimed French dancer who performed and created dances in venues as disparate as the Parisian foires, the patent theatres of London, and the Paris Opéra. She was the subject of a few portraits, two of which are of interest for the ways in which they were re-purposed after her retirement as a performer.

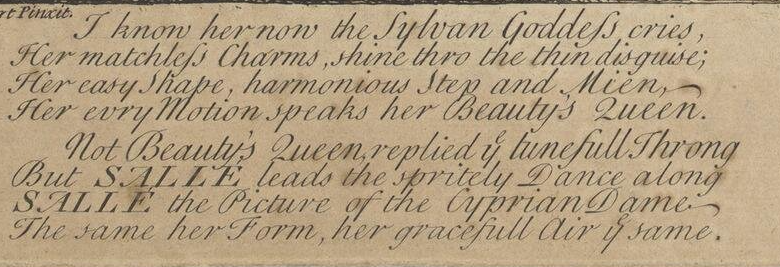

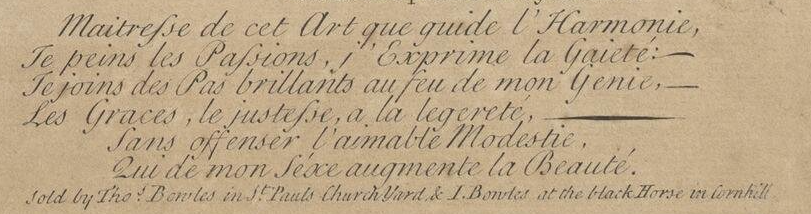

In 1732, after Sallé had reached the status of principal dancer at the Paris Opéra, her portrait was drawn by the fashionable artist Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). The Sallé painting was engraved and published by Nicolas de Larmessin (1684-1755), at that time the French royal family’s official portraitist. Lancret places Sallé within a ‘genre scene’ rather than producing a traditional portrait. Sallé, holding an attitude with great elegance, is in an outdoor setting that includes a temple of Diana on one side and a bevy of accompanying dancers on the other. Why the temple of Diana? According to James Hall, ‘the stern and athletic personification of chastity, is only one aspect of a many-sided deity’,1 but it is most probably the aspect being evoked here. Lancret’s subject is not a reference to any known role of Sallé’s, but rather promotes her carefully cultivated personal reputation.2 Voltaire – who supported Sallé by writing letters of introduction for her during the early years of his own career – wrote about this portrait in his correspondence to the writer Nicolas-Claude Thieriot during April-May of 1732. Voltaire saw the portrait in Lancret’s studio,3 and expressed a general dissatisfaction with the English verse attached to it by John Gay and Alexander Pope (‘not convenient’); nor did he approve of the French verse by Pierre-Joseph Bernard (‘not good’).4 All the poets celebrate Sallé’s virtue, although Bernard would later go on to slander Sallé’s name in a privately-circulating verse.5

The bilingual approach to the versification suggests that the dual publication of the engravings in both Paris and London was a plan from the outset. Sallé had performed in London during the 1730-31 theatre season and would return there for the 1733-34 and 1734-35 seasons, so her promotion through this elegant portrait would have been timely. Garnier’s engraving for the fraternal publishers Thomas Bowles II and John Bowles in London is a reverse of the original image.

Both the Paris (de Larmessin) and London (Garnier) engravings were re-purposed. A detail from de Larmessin (the figure of Sallé alone) would become – with the addition of some hand colouring – “Mlle. Sallé règne de Louis XV. d’après Lancret 1730” or plate 58 in an obscure series going by the title “Bureau des modes et costumes historiques.”6 Sallé’s name is still used in the title, although its function is simply to present her costume rather than celebrate her renown as an artiste.

The Garnier engraving also acquired colour in its afterlife as an image simply entitled ‘Dancing’. This was issued by the London-based publisher Robert Wilkinson sometime after he acquired John Bowles’s remaining stock on the latter’s death in 1779.7 Wilkinson evidently had found a niche in publishing images of theatre interiors and exteriors – the digital collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum London includes numerous such images as well as some of the publisher’s theatrical portraits. Wilkinson reissued images of theatre manager John Rich (1692-1761) as Harlequin and of the actor-manager David Garrick (1717-1779) under their own names, but appears to have decided that Sallé’s name would not prove a draw with purchasers over forty years after her final performance at Covent Garden Theatre.

Just as she was retiring from the Paris Opéra, a portrait of Sallé by Jean César Fenoüil was announced in the Mercure of January 1740. The image promotes Sallé as ‘La Terpsicore Françoise’: Terpsichore was the Greek muse of dance, and so this is a most fitting tribute to an acclaimed dancer at the end of her public career. Sallé’s biographer Émile Dacier makes a good case for the writer Titon du Tillet as a likely commissioner of this work.8 Sallé’s persona as a most virtuous woman is indexed in three ways.Verses by Paul Desforges-Maillard conclude by celebrating her expressive capacity as well as her self control: “Love is in her eyes, Virtue in her heart.”

The single turtle-dove in Sallé’s hand can evoke either chastity or love and constancy. The rose in her hair refers to an entrée ‘Les Fleurs’ which she created for Rameau’s opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (Paris Opéra, 1735). Sallé assumed the role of the Rose, queen of the flowers, who collectively endure an assault by the rude north wind Borée but are rescued by the gentle west wind Zéphire. Quite unusually, the action of this dance scene is supplied on the final page of the livret for the opera. Sallé may have wished to draw on the rose’s particular associations with the Virgin Mary — certainly the choice of flower by the painter is a reference to her role in the ‘Ballet des fleurs’ .

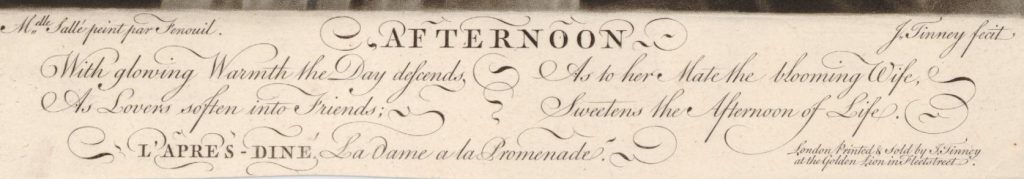

The engraver Petit repurposed this portrait, announcing the new work in the Mercure for July 1742 under the title “L’après-diné – la Dame à la Promenade“. Details such as a hat, necklace and bracelet have been added to the plate, while the attributions of artist and engraver have been retained but changed in format. The original engraving has: “Fenouïl pinxit” and “Petit Sculpt.”; the reissue has: “M.elle Sallé peint par Fenoüil” and “Gravé par Petit”. Before his death in 1761, an enterprising British engraver and seller John Tinney repurposed the image yet again as ‘Afternoon’ in a series of four images depicting the times of day. (According to the British Museum, the remaining three were taken from drawings by François Boucher.) ‘Afternoon’ is accompanied by a fresh poem that reflects its new function depicting a good wife in the afternoon of her life. Tinney retains the credit to the painter and Petit’s second title, while claiming for himself the role of engraver, ‘J. Tinney fecit.’

This re-purposing of images reflected the economic realities of the eighteenth-century print trade: engraved plates represented a considerable investment in time and money, and if they could be made to serve more than one purpose, so much the better. Sallé swiftly lost her celebrity status once she no longer performed at the Paris Opéra, and so the image represented more to its engraver Petit in its new guise. Sallé, although respected in her day as a performer and as a creator of dancers, appears to have lived a modest lifestyle – nor did her circumspect behaviour yield incidents which would render her of sustained interest on a personal level to a broader public.

1) Hall, James. ‘Diana’ in Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art second edition (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008), pp. 105-106 (p. 105). The symbolic interpretations of turtle-dove and rose in this blog are also derived from Hall.

2) For further on Sallé’s reputation see Sarah McCleave, ‘Marie Sallé a Wise Professional Woman of Influence’, Women’s Work: Making Dance in Europe Before 1800 (Studies in Dance History), edited by Lynn Matluck Brooks (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007), pp. 160-182.

3) Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, 14 April 1732 (new style). Lettre 462, Voltaire’s Correspondence, edited by Theodore Besterman (Geneva: Institute et Musée Voltaire, 1953), vol. 2, pp. 299-301.

4) Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, 26 May 1732 (new style). Letter 476, Voltaire’s Correspondence, volume 2, pp. 320-321 (p. 320).

5) Reproduced in McCleave, ‘Marie Sallé’, p. 165.

6) This is the only such plate I have discovered to date.

7) For Robert Wilkinson’s acquisition of Bowles’s stock, see the biographical note on the former at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG51109, accessed 7 December 2022.

8) Émile Dacier, Une danseuse de l’Opéra sous Louis XV. : Mlle Sallé (1707-1756) d’après des documents inédits (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1909), pp. 231-32. For a chatty letter from Sallé to du Tillet dated 27 October 1742, see Dacier pp. 243-247.

‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (Paris: Lancret and de Larmessin, [1732-1735]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

Alexander Pope and John Gay, “I know her now”. Detail from ‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (London: Thos. Bowles and I. Bowles, [1730s?]). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Pierre-Joseph Bernard, “Maitresse de cet Art”. Detail from ‘Mlle Sallé’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret, engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. (London: Thos. Bowles and I. Bowles, [1732-1767]). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

‘Dancing’, drawn by Nicolas Lancret. (London: Robert Wilkinson, [1779-1827]). (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Paul Desforges-Maillard, “Les Sentimens aves les Graces”. Detail from ‘Mlle Marie Sallé La Terpsicore Françoise’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by Gilles-Edme Petit. (Paris: Petit, [1742]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

‘Mlle Marie Sallé La Terpsicore Françoise’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by Gilles-Edme Petit. (Paris: Petit, [1742]). Copy: Bibliothèque nationale de France/Gallica. Public domain.

Anonymous, “With glowing warmth the day descends”. Detail from ‘Afternoon’, drawn by Jean-César Fenoüil, engraved by John Tinney. (London: J. Tinney, [1740s-1761]). Copy: British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The next post will consider the Irish dancer Lola Montez (1820-1861).

Above: Anonymous print of Marie Sallé in ‘Ballet des fleurs’ from the New York Public Library.

Below are further proposed themes, subjects, and and images for the Dance Biography blog:

“ESCAPING EFFIE” Noblet, Lise (1801-1852)

Costume sketch, Hautecoeur-Martinet, number 728, Lise Noblet in La Sylphide as Effie, circa 1832. Houghton library, George Chaffee Dance Collection.

Grévedon, Henri, 1776-1860 (artist), and Alphonse Bichebois, 1801-1850 (lithographer). ‘Melle Noblet de l’Académie royale de Musique.’

Paris, [182-]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b66f4be0-beb3-0132-6b2c-58d385a7bbd0

Maleuvre , Louis, b. 1785 (engraver). ‘Costume de Mlle. Noblet dans La révolte au sérail ballet. Acte II.’ Paris, [1833?]. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b70016876

Vigneron, Pierre Roch, 1789-1872 (del.). ‘Melle. Noblet, Académie royale de musique.’ [Paris], [c. 1830]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/dbac5e70-beb3-0132-babd-58d385a7bbd0

FORTHCOMING Parisot, Mlle (c. 1775-after 1837) ‘Body on Show’ by Sarah McCleave

FORTHCOMING Sallé, Marie (1709?-1756) ‘La Vestale’ by Sarah McCleave

FORTHCOMING: Santlow, Hester, ‘The Loves of Mars and Venus’ (provisional title) by Moira Goff.

FORTHCOMING Subligny, Marie-Thérèse (1666-1735?) ‘The First Lady of Dance’ by Jennifer Thorp.

Mariette, Jean, 1660-1742 (engraver). “Mademoiselle Subligny dansant à l’Opéra.” Paris, [169-?]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-0c52-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

THE GENIUS OF DANCE: Taglioni, Maria (1804-1884)

‘Taglioni.’ Paris: F. Sinnett (rotonde 10) galerie Colbert [183-?]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a64800a0-dd56-0132-0538-58d385a7bbd0

Grévedon, Henri, 1776-1860 (illustrator). [‘Marie Taglioni.’] [Paris, ca.1840]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1840. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1d7d39c0-dd5a-0132-3af0-58d385a7bbd0

Lane, Richard James, 1800-1872 (artist), after Alfred Edward Chalon. ‘Marie Taglioni [fac. sig.].’ [London], 1831. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-0c43-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Lange, Jane (Ange-Louis Janet, 1811-1872), illustrator, lithographer, engraver. ‘Scène des fleurs, dansée par Mlle Taglioni (Académie Royale de musique).’ https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8427166w

Noël, Alphonse Léon, 1807-1884 (lithographer). ‘Mlle Taglioni Académie de Musique.’ Paris, [c.1840]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/94bd81d0-dd59-0132-ff26-58d385a7bbd0

Vigneron, Pierre Roch, 1789-1872 (artist). ‘Melle. Taglioni.’ Paris, [183-]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/0a5ea010-dd59-0132-6afa-58d385a7bbd0

Offers of contributions, on the above or other subjects, to the editor Sarah McCleave, s.mccleave@qub.ac.uk