Augusta Maywood (1825-1877?)

By Lynn Matluck Brooks

Franklin & Marshall College

As the early United States was forming its own cultural products, the ballet stage was dominated by French performers. The artistry, renown, and earnings of some of these imported ballerinas inspired young Americans with stage ambitions. Among these, Augusta Maywood became one of the earliest home-grown ballerinas of repute (see Fig. 1), debuting with a competitor to that title, Mary Ann Lee, in The Maid of Cashmere, as the opera-ballet La Bayadère was called in their joint season (December 1837 to January 1838) at the Chestnut Street Theatre, Philadelphia. The young dancers—Augusta was twelve, Mary Ann thirteen or fourteen—appeared in the opposing roles of Zelica/Zoloé (Maywood) and Fatima (Lee).[1] For the preceding year or two, they had been students of Philadelphia dancing master P. H. Hazard, who claimed Paris Opéra training. Both girls’ tuition under Hazard was paid for by Philadelphia theatre manager Robert Maywood. Augusta, born in New York City, was his adopted daughter (he married her actress-mother after Augusta’s parents divorced); she spent most of her youth in Philadelphia. Her exposure to the stage from childhood surely contributed to Augusta’s theatrical savvy, compensating for her short period of formal study. Charles Durang, an astute observer, remarked on her “natural abilities for agility and grace.” Another Philadelphia critic wrote that Augusta’s début “created quite a sensation in the public mind,” owing to her “precision” as a dancer, despite her youth, and her possessing “the mind and the science of the artiste.”[2]

Durang wrote, “Augusta Maywood really was a prodigy. […] At one bound this talented girl stood beside the best terpsichorean artistes that we had in the country.”[3] He shrewdly added that, “With the furore this precocious child of dance had elicited, it would have proved good policy, while the excitement raged, to have starred her through the country.” Instead, her parents hastened her to Paris to study at the Académie Royale, “losing the pecuniary rewards which a tour in the United States would clearly have gained.” But perhaps manager Maywood saw that, with the polish of the French academy and the lustre of a Paris Opéra début, the still-malleable Augusta would be unbeatable as the first and greatest ballerina the U.S. had produced. In Paris, “her improvement was wonderful,” Durang wrote, and she was granted a coveted début at the Opéra, which “resulted in a brilliant triumph.” A reporter for Philadelphia’s National Gazette obtained entry to “the dancing room of the Grand Opera” to see “the little prodigy who had aroused such just admiration” in her U.S. début.[4] He praised “the exhibition of her highly developed powers, that attracted yesterday,” on the Opéra stage, “the zealous admiration of her graceful associates, and excited, naturally enough, the vanity of her skilful master, M. Corallie [sic], principal ballet master in the Academie Royale.” Perceived as a modest, dutiful American daughter, Augusta, this commentator assured readers, showed “no vulgar display of person, no attitudinizing appeals to the coarse sensualist; she moves in a region far beyond this—where all is grace and beauty—realized as those ideas can only be, if ever, of the soft, swelling movements of a buoyant and exquisitely formed girl, whose look of youthful innocence dispels every unchaste vision.”

Paris critic Théophile Gautier saw Augusta differently at her Opera debut of 25 November 1839, when she danced in the canonical ballets Le Diable boiteux and La Tarantule.[5] He noted her “distinctive type of talent,” which revealed “something brusque, unexpected and fantastic that sets her utterly apart” from the stars or aspirants of that theatre. She “has now come to seek the sanction of Paris, for the opinion of Paris is important even for the barbarians of the United States in their world of railroads and steamboats.” Americans—be they “Indians” or entrepreneurs—were all, to the refined continental viewer, savage. Still, “for a prodigy, Mlle Maywood really is very good.” And, blending together his conceptions of American industrial drive and the barbaric U.S. population, Gautier found Augusta “very near to being pretty,” with her “wild little face, […] sinews of steel, legs of a jaguar, and agility not unlike that of a circus performer.” Beyond her wild animal qualities, she faced the Paris audience with perfect tranquility: “You would have thought she was simply dealing with a pit full of Yankees.” We can also gather from Gautier details of Augusta’s technical accomplishment: “almost horizontal vols penchés,” turns in the air, “tours de reins,” her “small legs, like those of a wild doe,” striding like Marie Taglioni’s. In December 1839, Augusta’s name appeared on the payroll of the Paris Opéra.[6]

The wildness Gautier perceived in La Petite Augusta won out in her nature over the “innocence” American commentators initially praised as they read their desires onto the young ballerina. In 1840, still a teenager, she eloped with her Paris Opéra partner, Charles Mabille (1816-1858), bore a child, abandoned husband and baby, and toured throughout Europe—Lisbon, Vienna, Budapest, and Milan, dancing with the most renowned ballet stars in works by leading choreographers, often in starring roles. Augusta settled at La Scala, Milan, in 1849, ascending to prima ballerina assoluta there before retiring in 1862. She often danced in other Italian cities as well in this period but, apparently, Miss Maywood kept abreast of doings back home: among her many triumphs in Italy was her balletic staging of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, created soon after its U.S. dramatization (1853).[7] She also toured with her own ballet troupe and starred in her greatest hit, the ballet Rita Gauthier, by Filippo Termanini, based on Dumas’s La Dame aux camélias.

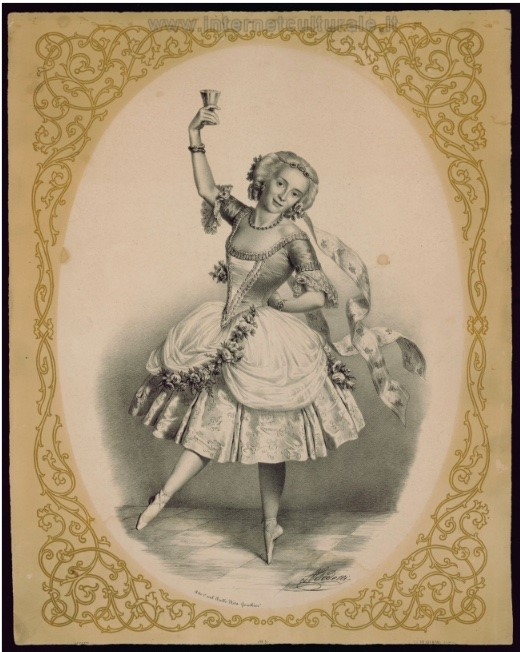

Figure 2) Maywood by Bedetti, NYPL. Public Domain.

Although Robert Maywood joined Augusta in Italy while she was touring (sometime during the period between 1852 and 1855) and lived there at her expense for a few years, she eventually sent him back to the U.S. where he died in obscurity. But long before that point, U.S. commentators had excoriated Augusta’s independent streak, damning their former darling for abandoning her doting parents, then her husband and child, and yet somehow, infuriatingly, being rewarded with success. Philadelphia theatre manager Francis Wemyss wrote of his dashed hopes for an American theatrical model in Augusta: “She has deserted her husband, and the heartless letter in which she recommended her child to the care of its father, at the moment she was abandoning him for the arms of a paramour, proves that her heart is even lighter than her heels. The very brilliance of her opening in life has been her ruin; the stage again pointed at as impure and immoral”[7]—this the greatest of her sins for Wemyss. Augusta, “who would have been the pride” of the stage “as an American artiste—who had gained the highest honors abroad—has become its shame: and thus I draw the veil upon her and her crimes for ever, hoping she may never attempt to appear upon the stage of her native country again.” Durang’s condemnation was at least as indignant: “let us draw the veil of oblivion over our regrets, over her and her crimes. In her lovely villa on the beautiful banks of the Arno, in sunny Italy, where she resides in seeming happiness, she may yet die in the conscientious throes of a guilty heart.”[9]

Instead, Augusta retired to Vienna, where she taught dancing– later lived peacefully in a villa on Lake Como.

References

[1] This season is covered in Charles Durang’s History of the Philadelphia Stage, between the years 1749 and 1855, arranged and illustrated by Thompson Westcott (Philadelphia: Thompson Westcott, 1868), vol. 4, ch. 50-51; the Public Ledger newspaper, Philadelphia; and the same city’s Weekly Messenger. See also Costonis, Maureen, “’The wild doe’: Augusta Maywood in Philadelphia and Paris, 1837–1840,” Dance Chronicle vol. 17, no. 2 (1994): 123-48; and Winter, Marian H., “Augusta Maywood,” 118-37 in Chronicles of the American Dance, ed. Paul Magriel (1948; New York: Da Capo Press, 1978). Documents on Maywood are available at New York Public Library-Performing Arts, Dance Clipping File, Augusta Maywood, *MGZR.

[2] Dramatic Mirror (20 November 1841): 113.

[3] Durang, History, vol. 4, ch. 51, p. 147-48.

[4] “La Petite Augusta,” National Gazette (18 December 1838). The reference in the next line is to renowned choreographer and dancing master, Jean Coralli, with whom Augusta studied for a year and a half in Paris, along with her classes from another great artist of the ballet, Joseph Mazilier (Costonis, “The Wild Doe,” 129-30).

[5] Gautier, Théophile. Gautier on Dance, ed. and trans. Ivor Guest(London: Dance Books, 1986), 79-80. The ballets mentioned were created for Fanny Elssler: Le Diable boiteux (1836, Paris Opera), music by Casimir Gide, choreography by Coralli; La Tarantule (1839, Paris Opera), libretto by Eugene Scribe, music by Gide, choreography by Coralli.

[6] Augusta Maywood’s contract with the Paris Opéra for the period 1st December 1839 to 30th November 1840 is preserved at the Paris Archives Nationales, AJ/13/195, Personal dossier, “Maywood, Mlle.” Annotations on it reveal that her core salary of 1500 francs was doubled to 300o francs during the signing session that involved Augusta, her mother Louisa Maywood and Director-Entrepreneur Henri Duponchel.

[7] Parmenia Migel Ekstrom, “Augusta Maywood,” in Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), 518.

[8] Wemyss, Francis. Twenty-Six Years of the Life of An Actor and Manager, v. II (New York: Burgess, Stringer and Co., 1847), 293.

[9] Durang, History, vol. 4, ch. 51, 148.

Images

Fig. 1). “La petite Augusta, aged 12 years, in the character of Zoloé, in the Bayadère,” by E. W. Clay, New York, 1838. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 22 May 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/05fe3de0-dd5d-0132-f092-58d385a7b928

Fig. 2.) “Augusta Maywood,” by Augusto Bedetti, Ancona, c. 1853. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 22 May 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/512b72c0-1454-0133-4430-58d385a7b928f

Fig. 3). “Atto 1. nel ballo ‘Rita Gauthier’” by A. Bedett[i], c. 1856. Biblioteca nazionale universitaria – Torino – IT-TO0265, identifier: IT\ICCU\TO0\1860890.