Sir Bruce Hart: Living it large in Lockdown

Our latest blog post comes courtesy of Lauren Browne, PhD reseacher in the School of History and student assistant at Special Collections. Here she reflects on her journey with Sir Bruce Hart during lockdown 2020, in which she created a Storymap based on his travel diaries, held in Special Collections, MS 49.

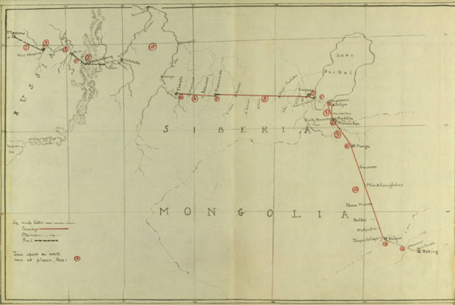

Shortly before Northern Ireland was plunged into lockdown in March 2020, I began to work on Sir Edgar Bruce Hart’s Travel Diary from June to August 1894. Over the extended quarantine, I followed him as he journeyed from Peking, through the Gobi desert, across Siberia and Europe to Paris. With my own holiday plans on hold, I relied on Hart’s descriptions of the people and places he experienced to escape my Belfast apartment. As Hart travelled, I plotted his route on the software Story Map JS. You can find the finished project here: https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/ad1f30647959025a7cdea4e9e9352f27/sir-edgar-bruce-hart-from-peking-to-paris-summer-1894/index.html

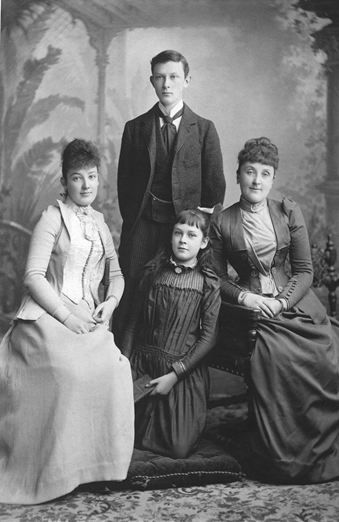

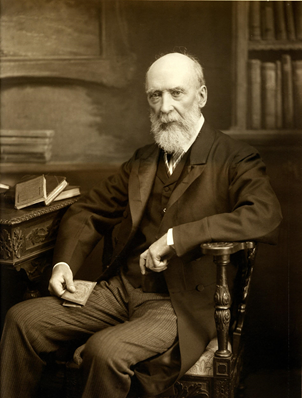

I knew very little about the man I went on this journey with, except that Bruce Hart (1873-1963) was the son of Sir Robert Hart (1835-1911), Inspector General of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs. It wasn’t until we returned to on-site working, and I could access reading material on Sir Robert Hart, that I discovered the context of Bruce’s journey and what happened after he returned to England. Although Robert Hart lived and worked in China, his wife, Hester, and their three children – Evelyn, Bruce, and Mabel – had lived in England since 1882.

In 1894, when Bruce Hart was nineteen and failing at Oxford University, he became engaged to Caroline Moore Gillson. The match was not approved by Bruce’s parents, who considered him to be too young. Robert Hart wrote ‘marriage means setting up one’s own establishment and that those who marry young ought to be sure about their “ways and means”’ before marriage’.[1] As Bruce was still at university, and had not yet entered a profession, his father thought him unable to support a wife and family. Despite his family’s objection, Bruce remained adamant that he would marry his sweetheart. The affair seems to have caused his parents great worry, and Robert Hart makes frequent reference to his concerns through his correspondence with his London agent, Campbell. In a bid to prevent the marriage, in spring 1894, Bruce Hart was appointed a ward of the Court of Chancery. This meant that he would need to receive permission from the court before he could marry, otherwise he could be held in contempt.

MS 15/6/1/B33

Also around this time, Robert Hart sent for Bruce to come to Peking via Chicago. Bruce arrived in Peking on 6th September 1893, and appears to have lived a quiet life there. According to his father, Bruce spent his time ‘riding, fiddling, reading, doing some Chinese and not caring much for society’.[1] Despite this, Robert notes that Bruce was still ‘set on marrying Miss G!’[2] Indeed, his father blames an illness Bruce suffered in April 1894 on the situation; ‘I begin to think that to save his health, intellect, and life, we’ll have to give way, and let him be happy after his own fashion for he’s bent on marrying Miss G.’[3] Eventually, Bruce began his journey home after spending nine months in China. His father commented that his son’s visit was ‘a year of wasted time and full of worry…’.[4]

In letters to Campbell, Robert Hart noted his son’s plans to travel across Siberia with ‘the Russian minister’s party’. On Sunday 17th June 1894, the party left from the Russian Legation in Peking. Bruce meticulously recorded every day of their journey, along with observations on the places and people he encountered. He frequently complained about the often ‘monotonous’ scenery, the mule litters, and the sub-par accommodation. By the time they reached the Gobi desert they are required to travel in several tarantasses. Bruce described the vehicle as ‘rather like a huge cradle, with a hood, and apron’, it was ‘wide enough for two people’ but they had to lie down ‘at full length’.[5]

Bruce Hart’s depiction of a tarantass in his travel diary

MS 49/1/082

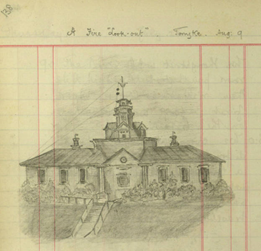

The diary is also littered with drawings Bruce Hart made along the way. They are often of the towns along the route, or the people they encountered. There are some beautiful depictions of towns such as Tomsk and Nizhny-Novgorod.

Drawing of a building in Tomsk dated 9th August

MS 49/1/138

Drawing of Nizhny-Novgorod

MS 49/2/002

Some are not as kind as others. In Perm he illustrates a ‘fellow traveller’ and captions it ‘a thing of beauty is a joy forever?’

Bruce Hart frequently describes the customs of the various peoples he meets. Observing that

‘it is a Russian habit that when leaving the house of a man, whose guest you have been, you all sit down together just before starting. It is not necessary that you shd. be seated more than 5 seconds, & today we were only seated about 10. Next the Russians make the sign of the cross & kiss each other on both cheeks. When a gentleman says goodbye to a lady he kisses her hand, & she his forehead.’[6]

MS 49/1/65-66

Other observations include the hierarchy present in Mongolian society, the building of the Trans-Siberian railway, Russian goldmining, and the conditions of a prison is Irkutsk. Hart is particularly impressed with a Buddhist monk he meets in the Tamchinskiy Datsan: ‘I was very much impressed by his appearance: He hardly moves at all: unless absolutely necessary & when he sits down he remains perfectly still until he gets up, and only moves his lips when he speaks… It appears that several Llamas [sic.] have been known to remain without moving for 2 & 3 years.’[7] He also includes an incredibly detailed description of a guided tour he took in Moscow.

Throughout the course of the diary, Bruce makes no mention of Caroline Moore Gillson and their engagement, or any of his family members. In a letter from Robert Hart to Campbell, dated 11th November 1894, he states; ‘Bruce has not written a word since he left Peking: I am surprised, or rather – no, not surprised – grieved.’ His son had joined the Customs Service in the London Office as a secretary the same month.

Edgar Bruce Hart and Caroline Moore Gillson married on 19th December 1894, just three months after he returned to England from China. Despite going against his parents’ wishes, Bruce’s father stated ‘the thing’s a fact now and we must accommodate ourselves to it: I’m not going to fall out with him for marrying his sweetheart…’.[8] Indeed, Bruce and Caroline later travelled to China on honeymoon in spring 1895. Unfortunately, Caroline suffered a miscarriage on their journey to Peking and they spent several weeks in Tientsin (Tianjin) to aid her recovery.

On 16th May 1895, the newlyweds arrived in Peking and Robert Hart took a great liking to his daughter-in-law. He thought Caroline’s ‘influence on [Bruce] is certainly for good’ and that she was ‘very quiet, composed, and self-contained.’[9] Two months into their visit, Robert reported to Campbell ‘She is very nice indeed and I like her better every day.’

To Robert Hart’s great delight, Caroline and Bruce welcomed a son – Robert Bruce Hart – on 26th September 1896. He was affectionately called Robin by the family, and his grandfather makes frequent reference to him inheriting the baronetcy after Bruce Hart. Unfortunately, Robin did not outlive his father and he died on 14th July 1933, leaving behind a son also called Robert. He inherited the baronetcy upon Bruce’s death in 1963, although he died without issue in 1970 and the title became extinct.

Bruce Hart’s travel diary provides a rare insight into a journey made overland from Peking to Paris in 1894. Hart’s descriptions and illustrations vividly bring to life the Lama settlements of the Gobi desert, the winding Oka River filled with steamers, and bustling market of Nijni-Novgorod. If – like me – you are in need of a good holiday and an escape from these cold winter nights, I highly recommend taking this journey with Bruce Hart. Thankfully you won’t need to travel in a tarantass!

- If you are interested in finding out more about the collection, both volumes of the travel diary have been digitised and can be found here: http://digital-library.qub.ac.uk/digital/collection/p15979coll7

- The Story Map can be accessed here: https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/ad1f30647959025a7cdea4e9e9352f27/sir-edgar-bruce-hart-from-peking-to-paris-summer-1894/index.html

- Further information on Sir Robert Hart and our collections can be found here: http://omeka.qub.ac.uk/exhibits/show/hart3511

[1] MS 49/1/65-66.

[2] MS 49/1/85-87.

[3] The I.G in Peking, II, 957 Z/645

[4] The I.G in Peking, II, 973 Z/661

[5] MS 49/1/20-21

[6] The I.G in Peking, II, 908, Z/596.

[7] The I.G in Peking, II, 908, Z/596.

[7] The I.G in Peking, II, 924, Z/612.

[8] The I.G in Peking, II, 926, Z/614.

[9] The I.G in Peking: Letters of Sir Robert Hart Chinese Maritime Customs 1868-1907, eds. John King Fairbank, Katherine Frost Bruner, Elizabeth MacLeod Matheson, II (London, 1975), 879, Z/567.

Reading travel diaries from people who travelled in China at this time are always most interesting, but I think your travel map has to be the most innovative I ‘ve seen. For once all these strange places with unfamiliar names come alive, and together with the sketches and diary entries it adds another dimension to the story. Also, you get a real idea of just how far he travelled. I really enjoyed reading it and learnt a lot from it. Thanks.

Very glad that you enjoyed it Keith! We will be sure to pass on your comments to Lauren (the author)!

Fascinated to read this account of the Bruce family; I met Sir Robert as a child when he lodged with my great-aunts in a farmhouse in Ilsington in Devon until his death in 1970. I still have some linen and a blanket from their house that bears his laundry tag!

Thanks for the lovely comment, Helen. We’d love to hear more about your memories of Sir Robert! If you would like to contact us, our email is: specialcollections@qub.ac.uk