Music-making in the Customs Service

The following guest blog is by Dr. Andrew Hillier, Honorary Research Associate, University of Bristol.

A personal letter from Robert Hart to a young official shows how important music-making was in the Customs Service.

After spending his first six years as a young Customs official in Hankou, in September 1879, Harry Hillier received one of Robert Hart’s inimitable letters informing him he was to proceed to Niuzhuang. Pending the arrival of the new Commissioner, Lewis Stanten Palen, he was to be temporarily in charge and, having set out a list of specific instructions and emphasising the importance of not doing anything ‘new’, Hart continued,

I take it for granted that you know enough Chinese to be able to talk with the Taotai easily and that you are well enough up in Customs Regulations to ensure your not making a mistake in the conduct of ordinary business … I trust this opportunity of showing your value will be appreciated by yourself and prove to me that I may look to you as a man fit for use in the future’.[1]

Customs men reacted in various ways to this typically challenging approach. Failing to impress Hart with his athletic prowess, Hillier’s contemporary, Paul King, always found it difficult to get on with the I.G. [2] Those with an interest in music had a better chance and, although, according to his son, Harold, Hillier played the violin ‘with greater zest than skill’, it was sufficient for Hart’s purposes, when he was assigned to the Customs’ office in Peking in early 1881. [3]

Hart already knew Hillier’s brother, Walter, who was Assistant Secretary in the Peking Legation, and this gave him a good start when he arrived. A letter from Hart to Campbell, shortly before he arrived, appending a list of sheet music, gives an idea of what was required in terms of musical ability and, as we will see from the letter below, Harry Hillier was probably able to hold his own.[4]

It may also have helped him in his career as, soon afterwards, he was promoted to Assistant Audit-Secretary and then a year later, he was assigned to the London office, a prestigious appointment, which gave Duncan Campbell, the London representative, a chance to look at him. [5] However, Hillier’s time in England was overshadowed by illness, first that of his wife, Annie, whom he had recently married, and then of himself. Hart’s correspondence with Campbell and his letter to Hillier provide an insight into the way Customs men could at times be dealt with sympathetically and how, finding intimacy difficult, Hart used music as a way of building relations with them.

Following the birth of Edna (Eddie) Hillier on 4th July, 1883, Annie suffered complications and when these worsened, Campbell informed Hart,

Hillier’s wife is in a v. weak condition since her confinement and I should not be surprised if he were to lose her. The doctor having advised a change to the sea, he took her to Brighton for 10 days, but I do not think she has gained any strength; and he is now going to send her to his married sister in Cheshire. [6]

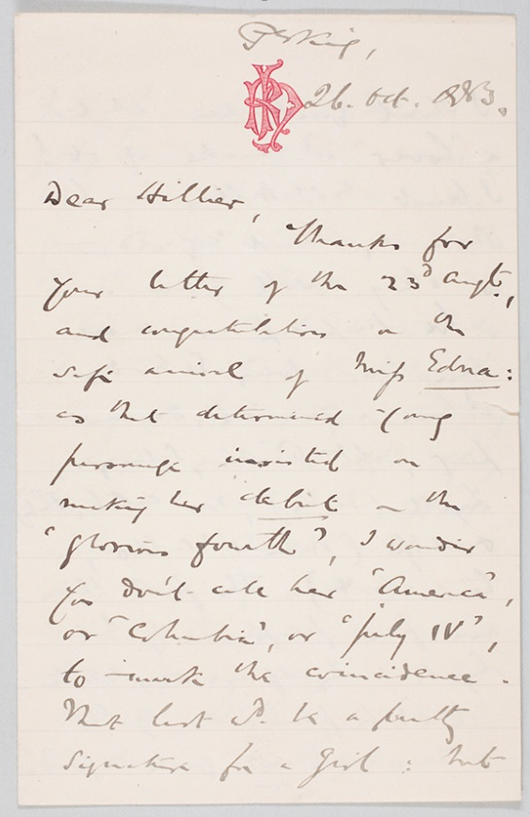

Eventually, she did pull through and, hearing of her recovery, Hart wrote to Hillier in light-hearted vein, commenting on the propitious date of Eddie’s birth,

Congratulations on the safe arrival of Miss Edna; as that determined young person insisted on making her debut on the “glorious fourth” I wonder you don’t call her America or Columbia or July IV to mark the coincidence. I don’t quite see what a ‘lover’ would make of it! I trust Mrs Hillier – to whom my kind regards – is strong + well again.

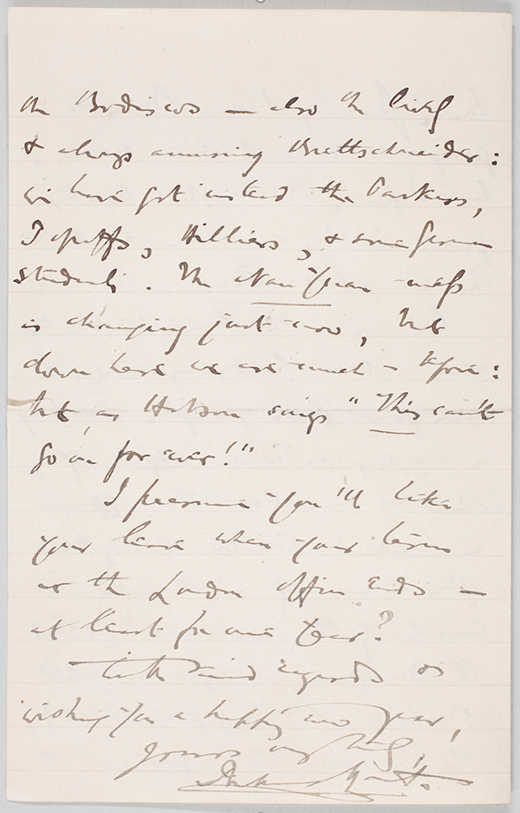

The letter then goes on:

We keep up our music here too. Every Saturday I have a musical dinner party, Mrs Pirkis[7], Scherzer, Lyall (violin), Van Aalst (flute), + self (violin + `cello, time about).[8] The first three are fine performers, but Lyall + myself are very weak: it wd be pleasanter if the others were not quite so good. From Germany I hear Bruce is going ahead with his music, but I fancy the most interesting group in this connection must be the Campbell Trio.[9]

Knowing it would take some time for the letter to arrive, he concludes by wishing Hillier a Happy New Year.

The fact that Hillier kept this and a handful of other personal letters from Hart shows how important they were to him, not least because of their amicable tone. Campbell’s solicitous approach was repeated when Hillier became ill after a routine operation, and he had to inform Hart that he was ‘in a precarious state’.[10] Only after the Customs’ eminent Physician, Dr Macrae, had been brought in, did he begin to recover. After home leave, Hillier and his wife and young daughter returned to China in late 1885. However, still weak, Annie soon fell ill again and Hart recorded in his diary, ‘Mrs Hillier, Tientsin, very ill: typhoid’.[11] They went to Chefoo in search of sea air but, the case was hopeless and Annie died on 23 July 1886.[12] There is no commiserating letter from Hart in the family papers. This, of course, does not mean that one was not sent, but had it been, Hillier would most probably have retained it with the others. But in the tragic circumstances, it may have gone astray.

Hillier would remarry and serve in the Customs for a further twenty-five years, the last fifteen as Commissioner. However, he would not return to Peking until after Hart had left and so would not take part again in his music-making. However, other members of the Hillier family would do so. Although Walter was no musician, his lively and extrovert wife, Clare, loved dancing and also, ‘plays dance music very nicely’ according to Hart’s diary, which has many references to her attending his parties. Harry’s younger brother, Guy, who would become the long-standing Peking agent of the Hongkong Shanghai Bank, would also come and play both harmonium and hand organ.[13]

From his letters book, it is clear that Harry continued to practise his fiddle, maybe to be ready should he be summoned again to Peking. But like many of his generation, towards the end of his career, he became disillusioned with Hart.

Nonetheless, he was a pall-bearer at his funeral and, by comparison with some of his colleagues, he could consider that he had enjoyed a good relationship with the IG. If so, that probably owed much to his ability to keep up with Hart’s music-making during the time they were together in Peking.

Mediating Empire was published in April 2020. My Dearest Martha: the Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier will be published in the autumn by Hong Kong City University Press. For details, see andrewhillier.org

[1] Letter, Robert Hart to H.M. Hillier, 12 September 1879 (Hillier Collection). For Hillier’s career and that of his two brothers, Walter and Guy, see Andrew Hillier, Mediating Empire: An English Family in China. 1817-1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020).

[2] Paul King, In the Chinese Customs Service: A Personal Record of Forty-Seven Years (London: Heath Cranton Ltd, 1930), see, especially, pp.234-244.

[3] John K.Fairbank, Katherine Frost, Bruner, Elizabeth Macleod Matheson (eds), The I.G. in

Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868-1907 (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975), pp. 25-6.

[4] See letter, Hart to Campbell, 5 January 1881, , no. 311, IG in Peking.

[5] See letter, Hart to Campbell, 12 February 1883, no. 402, IG in Peking.

[6] Letters, Campbell to Hart, 10 August 1883, no. 1094 and 31 August 1883, no.1103, in Chen Xiafei and Han Rongfang (eds), Archives of China’s Imperial Maritime Customs: Confidential Correspondence between Robert Hart and James Duncan Campbell, 1874-1907 (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1990).

[7] Bessie L’Eveque Pirkis, wife of A.E. Pirkis. From a photograph of portrait sketches of foreigners in Peking, Christmas 1877 (HPC DH-s019) https://www.hpcbristol.net/visual/dh-s019

[8] ‘Time about’ is a Scottish phrase, and is, probably, the correct reading here.

[9] Letter, Hart to H.M. Hillier, 26 October 1883 (Hillier Collection). Although the writing is, as usual, difficult to read, these are the best estimate of the names of the individuals and correspond with those mentioned in a number of similar letters, for example, 7 January, no. 395, and 11 August 1883, no. 429, and are annotated in IG in Peking. Albert Edmondes Pirkis, an accountant in the consular service (p.236, n.3); F.A. Scherzer was French and joined the Customs in July 1876 and came to the Peking office as 3rd Assistant in April 1882, Hugh Lyall had come to China in July 1880 and was now a 4th assistant in Peking and J.A. van Aalst was a clerk in the Peking office (p.441, n.2) Many thanks to Deirdre Wildy and the staff of Special Collections, QUB, for their painstaking deciphering of the letter.

[10] Letter, Campbell to Hart, 22 February 1884, no. 1172, Archives of China’s Imperial Maritime Customs.

[11] Hart, diary, 27 February 1886, Queens University, Belfast,Sir Robert Hart Collection, MS. 15/1/31, p.215.

[12] North China Herald, 23 July 1886, p.77.

[13] There are numerous entries in Hart’s diary for 1885, MS. 15/1/31; see, for example, pp. 52, 87,91,101,112 and 130 (quote)and, although Walter and Clare went back to England the following year, they returned in 1888 for one final year in Peking and will have continued seeing Hart. Returning in 1889, Guy would remain there for the rest of his life and no doubt continued to attend and play at Hart’s parties, certainly until his marriage in 1894. See also https://blogs.qub.ac.uk/specialcollections/hillier-called-a-glimpse-at-sir-robert-harts-papers-in-the-special-collections-queens-university-belfast/