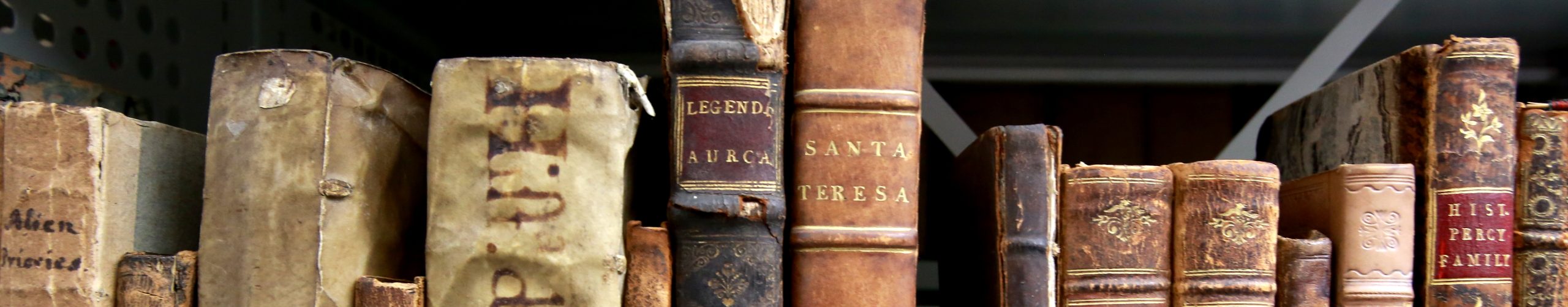

Heaney Manuscripts MS 20

First published in 1999, Seamus Heaney’s translation of the Old English epic poem Beowulf achieved both critical acclaim and commercial success. Beowulf: A New Translation won Heaney his second Whitbread Book of the Year Award in 2000[1] and the volume enjoyed “lengthy stints at the top of the best-seller lists in Britain and Ireland and in the United States.”[2] Heaney’s translation was first included in the 7th edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature in 2000, and 2002 saw the publication of the Norton Critical edition of his translation, edited by Denis Donoghue.

First published in 1999, Seamus Heaney’s translation of the Old English epic poem Beowulf achieved both critical acclaim and commercial success. Beowulf: A New Translation won Heaney his second Whitbread Book of the Year Award in 2000[1] and the volume enjoyed “lengthy stints at the top of the best-seller lists in Britain and Ireland and in the United States.”[2] Heaney’s translation was first included in the 7th edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature in 2000, and 2002 saw the publication of the Norton Critical edition of his translation, edited by Denis Donoghue.

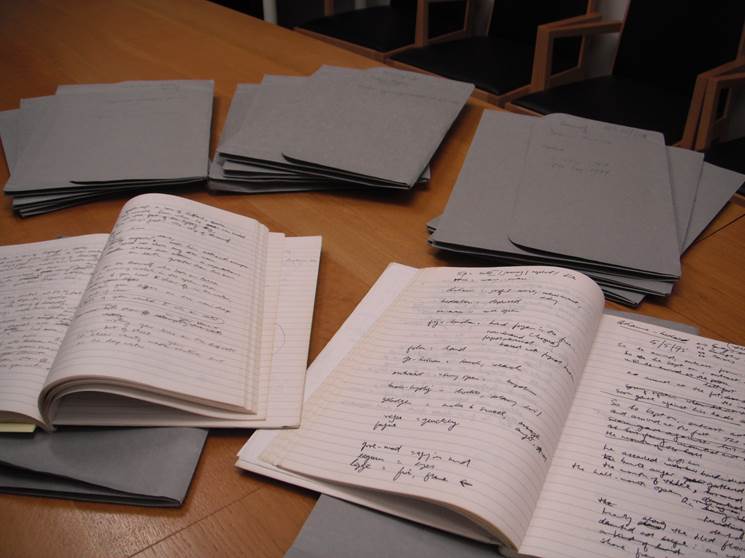

Donated to Queen’s University by Seamus Heaney in 2005, the Heaney Manuscripts (MS 20) consist of a total of nine archive boxes of material. The focus of the collection is predominantly on Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, but it also contains a small assortment of his other writings and correspondence, including several drafts of poems.

The Beowulf material in the collection includes the original manuscript drafts and subsequent typescripts drafts of Heaney’s translation – drafts from which the revision process of the poem can be traced – as well as later drafts sent out to various Old English experts for their comments, and a reasonably substantial amount of correspondence dealing with the practicalities of the publication process and detailing Heaney’s consultation with various academics.

Also of particular interest in MS 20 are two of Heaney’s student notebooks and assorted loose-leaf notes from his time as an undergraduate student here at Queen’s University, one of which – “First Arts: English (Language)” – documents the student Heaney’s first encounters with medieval English literature.

Heaney and Queen’s

Seamus Heaney came to Queen’s in 1957, on a scholarship from St Columb’s College, Derry, and he graduated with a first-class honours degree in English Language and Literature in 1961. It was during his time as an undergraduate at Queen’s that Heaney first seriously began to write, and he published a number of poems and prose pieces – including a short story – in various Queen’s student publications: the literary magazines Gorgon and Q, and independent student newspaper, The Gown.[3]

Seamus Heaney came to Queen’s in 1957, on a scholarship from St Columb’s College, Derry, and he graduated with a first-class honours degree in English Language and Literature in 1961. It was during his time as an undergraduate at Queen’s that Heaney first seriously began to write, and he published a number of poems and prose pieces – including a short story – in various Queen’s student publications: the literary magazines Gorgon and Q, and independent student newspaper, The Gown.[3]

Among the most influential of Heaney’s lecturers at Queen’s was Professor John Braidwood, who oversaw the English Language elements of the degree, and first introduced him to Old English literature. Affectionately remembered by another former student of his, Hugh Magennis (who would himself go on to become an preeminent Old English scholar) as a “no-nonsense Scot”, Braidwood was “an old style philologist who seemed to have a detailed knowledge of the history of every word you could think of”, [4] Braidwood taught Heaney on the first year history of the language course, “The Growth and Structure of the Language” and the second year course “Early English”.[5] An expert on Ulster dialects – the subject of his inaugural lecture – Braidwood’s teaching impressed upon Heaney an awareness of the validity and legitimacy of his regional culture and “offer[ed] a sense of belonging within a wider, richly varied English-language tradition”.[6]

Reflecting, some forty-odd years later, on the relationship between his undergraduate studies and his translation of Beowulf, Heaney commented,

[…] I couldn’t have done Beowulf if I hadn’t felt that I had some path into it, and it into me. And the path was to be found in the kind of noises I made in my early poetry and the kind I make in my speech. I was delighted to discover in ‘Digging’ two or three pure Anglo-Saxon lines, lines like “My father, digging. I look down…”. When I was at university the study of Anglo-Saxon meant something to me. I gradually came to love the weather and strange melancholy in ‘Seafarer’ and ‘The Wanderer’. I also very much liked ‘The Battle of Maldon’.[7]

Heaney and Medieval Translation

Since the publication of his celebrated translation in 1999, Beowulf is perhaps the medieval text with which Heaney is most commonly associated. However, as Conor McCarthy rightly points out,

Important as the Beowulf translation is […] it is not the full extent of Heaney’s poetic engagement with medieval poetry. In 1983, Heaney published a translation of the medieval Irish Buile Suibhne, and he has held an extensive dialogue with Dante’s Commedia involving translation, adaption and allusion across three books in particular: Field Work, Station Island and Seeing Things. [Heaney’s translation of Beowulf ] was followed by a Modern English translation of Robert Henryson’s Middle Scots text The Testament of Cresseid. Heaney’s translations and adaptations of medieval poetry, then, form a substantial body of work, drawn from across the medieval period and from a number of languages (Irish, Italian, Old English, Middle Scots), extending through much of his career.[8]

Moreover, Heaney’s literary response to medieval literature goes beyond direct translation. Many of his own original poems also show the influence of the medieval literature he first encountered as an undergraduate at Queen’s, perhaps most obviously in his 1975 collection, North, considered by Chris Jones to be “One of Heaney’s most powerful deployments of his knowledge of Old English”.[9]

“Heaneywulf”

Heaney’s engagement with a translation of Beowulf long predates the publication of his poem in 1999. He had been approached in the early 1980s by the editors of The Norton Anthology of English Literature with a commission to translate the poem, and a portion of his early work on the translation appeared as “A Ship of Death” in his 1987 collection The Haw Lantern. However, progress was slow, and, despite his “instinct that it should not be let go”,[10] Heaney eventually set the project aside, resuming it, as an autograph note on the inside cover of one of his notebooks explains, in March 1995, when an editor at Norton asked him for suggestions as to who else they might approach regarding the translation.

When Beowulf: A New Translation was published by Faber in 1999, much of the critical reception of the poem focused on Heaney’s use of Ulster and Irish dialect words – “the Hibernicization of the word-hoard”.[11] Responding to Heaney’s own framing of his poetic process in the introduction to the translation, critics and commentators were quick to locate and discuss the translation in terms of post-colonial theory, in which Heaney’s translation of such a canonical English literary text as Beowulf into Ulster English was viewed as an act of post-colonial appropriation. The extent of the Hibernicisms in the poem has perhaps tended to be over-stressed in such criticism (interestingly, they are more frequently attested in Heaney’s early drafts of the translation) and, as Chris Jones observes, “The reality of the identity politics of Heaney’s Beowulf is simultaneously less radical and more complex [than] the audacious possession of the cultural territory of a former imperial occupying power”.[12]

Beowulf

Preserved in a single manuscript dated to the early eleventh century, although likely to have been composed some two or three centuries before that, Beowulf has proved fertile ground for translators since Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin’s first complete translation of the poem (into Latin) in 1815. Largely the preserve of scholars in the eighteen and nineteenth centuries, the poem has steadily gained appreciation, interest and popularity from the late nineteenth century to the present day, aided in no small part by J. R. R. Tolkein’s seminal 1936 lecture “Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics”, which revolutionised the study of the poem.

The poem, or excerpts thereof, has been the subject of translations by poets as diverse as Alfred Lord Tennyson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Morris and Edwin Morgan and on average, one new translation of the poem appeared every two years in the twentieth century. The Heaney Manuscript Collection (MS 20) throws light on the poetic and translation process of the most widely known and popular translation of Beowulf in current use, and is of interest to scholars of Old English and twentieth-century poetry alike.

Works cited:

Ekestad, Nils. “Negotiating the Canon: Regionality and the Impact of Education in Seamus Heaney’s Poetry.” ARIEL 29.4 (1998) 7-20.

Heaney, Seamus and Karl Miller. Seamus Heaney: in conversation with Karl Miller. London: Between the Lines, 2000.

Jones, Chris. Strange Likeness: the use of Old English in twentieth-century poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Magennis, Hugh. Translating Beowulf: Modern versions in English Verse. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2011.

McCarthy, Conor. Seamus Heaney and medieval poetry. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2008.

[1] His first was awarded for his 1996 collection The Spirit Level.

[2] Magennis, 161. By 2000, Heaney’s translation of Beowulf had achieved 135 000 hardback sales world-wide (Miller, 43).

[3] Publications as an undergraduate student include four poems and a prose piece, all published under the pseudonym ‘Incertus’, as well as a poem, ‘Aran’ and an editorial, “The Seductive Muse”, published under the name “Seamus J. Heaney”.

[4] Magennis, vii.

[5] Eskestad, 10.

[6] Eskestad, 7.

[7] Miller, 40.

[8] McCarthy, 1.

[9] Jones, 213.

[10] Heaney, xxiii.

[11] Jones, 229.

[12] Jones, 229-230