Ethel Smyth: words and music

Image 1: Ethel Smyth in 1922. Image courtesy of the George Grantham Bain collection at the Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons. (Accessed 17 January 2023)

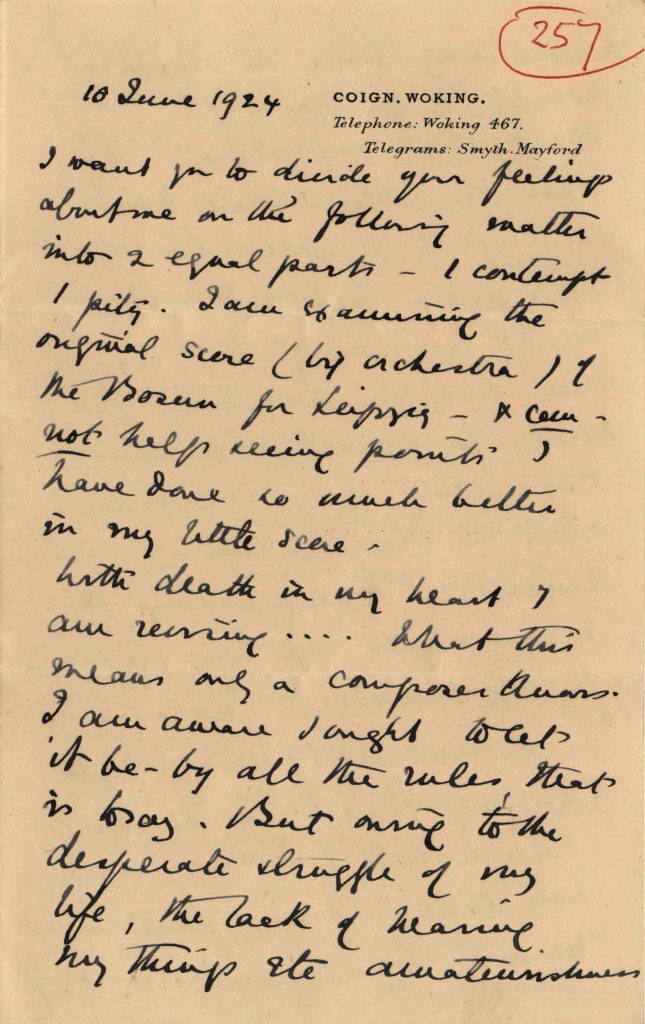

Image 2: Image courtesy of the Somerville and Ross Manuscripts at Special Collections, Queen’s University Belfast by permission of the Literary estates of Somerville and Ross.

“Ethel Smyth? She’s famous!” So remarked a visiting researcher, enquiring about an old letter displayed on my PC. I confess I hadn’t heard of Ethel before my involvement in the transcription of her correspondence and, almost eighty years after her death, was unaware of her status in the twenty-first century, but it seems that Ethel Smyth – composer, author, suffragist and feminist – has found acclaim once more.

Ethel certainly mingled with the famous: the Pankhursts, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West and Gustav Holst were among her acquaintances. She was a prolific letter-writer, and her many long-lasting friendships were often sustained via the postal service. One such friendship was with Edith Somerville, half of the writing partnership Somerville and Ross, famous for the Irish R.M. novels and stories. The Somerville family were landowners in County Cork where Edith lived for most of her life. She and Ethel (who resided in Woking, Surrey) wrote to each other frequently from 1919 until Ethel’s death in 1944.

Their exchange of letters (470 from Smyth to Somerville and 297 from Somerville to Smyth) is part of the extensive Somerville and Ross manuscript collection held in Special Collections, where a team of library assistants has been tasked with transcribing the text to make it searchable for academic researchers.

Staff work on a sequential batch of ten scanned letters at a time, but each batch will not necessarily be read in sequence, so we are given fragmentary glimpses into Ethel and Edith’s lives. The first reading of a batch involves typing out the text without spending too much time deciphering difficult words. The second, by a different participant, requires a more painstaking approach, examining any troublesome script and marking up suggested edits, which will then be assessed by the third reader.

Interpreting Ethel’s handwriting is challenging: the words merge into one another; her relationship with punctuation is often tenuous; she abbreviates many common words and, at times, writes whole passages in French. My impression is that these letters are the outpouring of a creative mind, someone with an endless flow of thoughts and (often extreme) opinions, whose rush to put these to paper outweighs the need for linguistic norms. While most unclear words can be deciphered from the context, proper names – and there are many – prove less straightforward.

Ethel’s letters are peppered with the names of fellow musicians, artists, writers, publishers, lovers (mostly women) and aristocrats (she was a snob and loved to name-drop). As a reference guide, a member of our team has compiled a comprehensive list of people mentioned in the letters, which reads as a who’s who of early twentieth century culture and influence.

Image courtesy of the Somerville and Ross Manuscripts at Special Collections, Queen’s University Belfast by permission of the Literary estates of Somerville and Ross.

Political events of the time are often discussed, including the 1926 General Strike, the Irish War of Independence and Civil War (Ethel had much to say about the Irish!). A common theme, close to both their hearts, is the struggle for women to gain recognition in the male-dominated arts world. Both she and Edith were suffragists, and her March of the Women became the official anthem of Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union.

Ethel emerged as a composer in the 1890s, producing many choral and orchestral works, six operas and a Mass. She did achieve success during her lifetime and was appointed a Dame in 1922, but was marginalised as a “woman composer” rather than being accepted as a composer among her peers1. Music and feminist scholars have begun to “reclaim her as a significant composer of worth who stood out from her generation”2. Two major performances of Ethel’s work took place in 2022: her Mass in D at the BBC Proms, and the opera, The Wreckers, performed for the first time in the original French, at Glyndebourne.

So yes, Ethel Smyth is a bit famous: after decades in the wilderness, her contribution to music is now being acknowledged. Her correspondence with Edith Somerville gives us a real insight into her life and work, but also, on a wider level, it is an invaluable source of material for cultural and social historians of the period.

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (1858–1944)

Edith Anna Oenone Somerville (1858-1949)

References

- Gates, E.(1997) ‘Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth’, Journal of Aesthetic Education 31 (1), 63.

- Kertesz, E. (2004) ‘Smyth, Dame Ethel Mary (1858–1944)’, in Oxford dictionary of national biography. Available at:

(Accessed 17 January 2023)

Text by Susan Headley