Ciphers, Codes and Notes: Crafting Knowledge in the Medieval and Modern Worlds

Visit our new online exhibition – Crafting, Codes and Notes: Crafting Knowledge in the Medieval and Modern Worlds

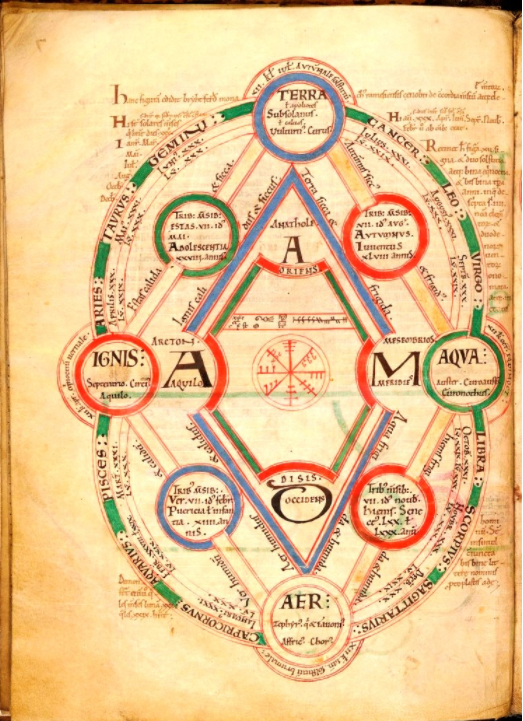

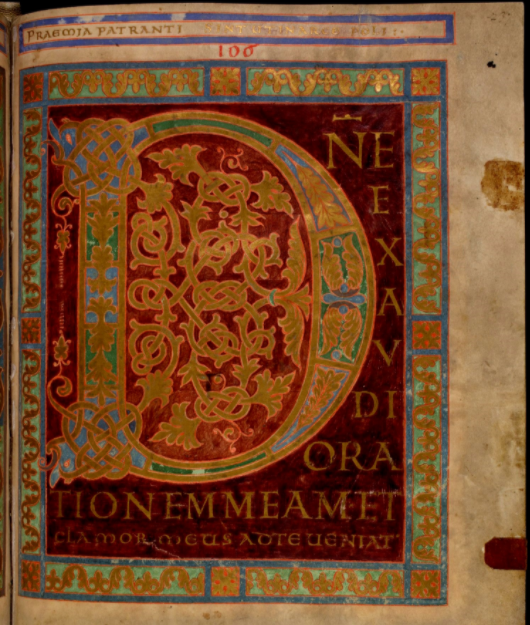

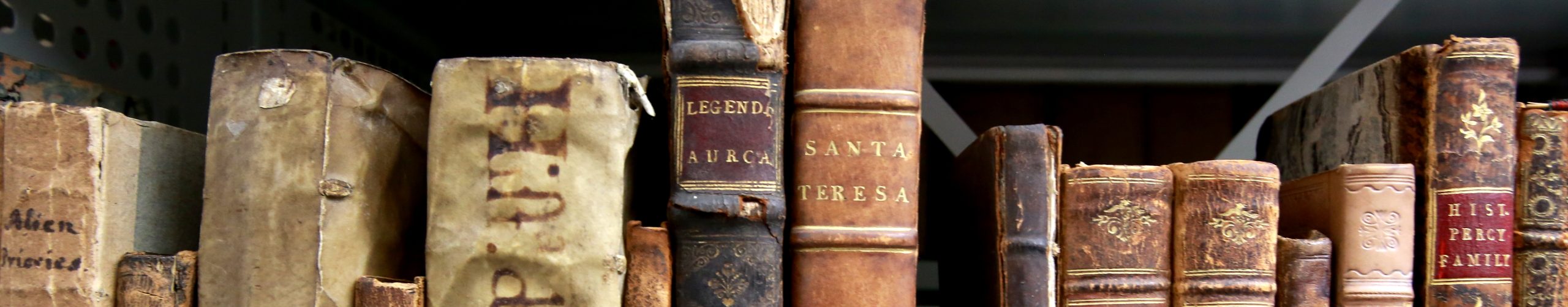

This fascinating exhibition is organised around key themes relating to early medieval intellectual culture. It comprises 10 sections exploring reproductions of early medieval manuscripts with glosses, diagrams, illuminations, ciphers and mystic writing. The exhibition offers a virtual tour of some of the most highly-prized early medieval manuscripts preserved in Switzerland, Austria, Germany, Italy, and England.

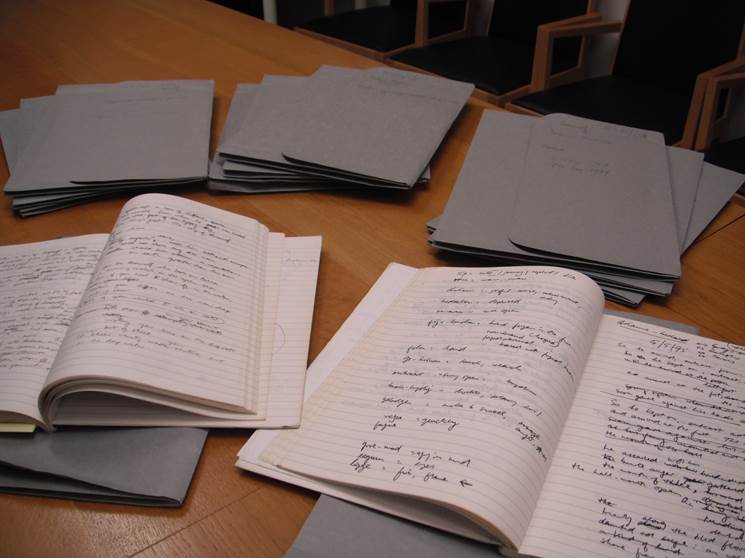

For the physical exhibition in the McClay Library (provisionally scheduled November 2020 – January 2021) these medieval materials will sit alongside modern examples of notetaking, debate, codebreaking and encryption. The modern examples are drawn from the works of the following literary figures connected with Belfast: Seamus Heaney, C.S. Lewis and Helen Waddell (manuscripts held in Special Collections). These writers were deeply indebted to the medieval past.

The exhibition has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in collaboration with the Leverhulme Trust. All text written, and images compiled by Dr Sinead O’Sullivan and Dr Ciaran Arthur, Queen’s University Belfast.

This exhibition “Ciphers, Codes and Notes” is fascinating and most informative. I have long been interested in encryption; if the purpose of language is to make meaning crystal clear then encryption seems to me to be the opposite use of language because it tries to obfuscate the meaning. If music is thought of as a language, since it also uses signs linked to sounds, then it fills a unique place, because although it is enigmatic, it can release in us deep emotions which move us, and which we seem to be unable to articulate in any other way.

There are striking similarities between the puzzles used by mediaeval writers and musicians. Just as you can have palindromes, so in music you can have music in retrograde, where the theme is played in reverse order. One could argue that Schoenberg’s Tone Row compositions are an example of the fascination with manipulating the basic row of sounds until they are unrecognisable. Of course it is well known that many composers have used the notes that spell the name of the composer B A C H (Bb in German) as the foundation of compositions.

The Music of the Spheres is interesting because you can find a similar idea in other cultures, most notably in ancient Chinese music. The Confucian view being that music’s purpose was to educate and therefore in religious ceremonies if the correct notes were used in the correct combinations then the Government would be in harmony and the people will be happy.

Thank you so much for your interesting comments. A captivating way to think of music and how it links to medieval thought and culture.

In the Introduction to his translation of Beowulf, Heaney describes his struggle to decode this among the greatest of poems in any language, “like trying to bring down a megalith with a toy hammer”. Anyone who has stumbled along through its Old English knows exactly what he means, but for Heaney to say this–he who “had been writing Anglo-Saxon from the start” of his poetic career–is both profoundly humbling and bonding, as in friendship. Heaney goes on to describe his introduction to the history of the English language at Queen’s, in his first arts year, when he learned the philological skills and instincts that again and again translation demanded of him: decoding the hidden secrets of one, very different language, then encoding them across 12 centuries into another, our own. An example he gives is translating the poem’s first word, ‘hwaet’, into the simple Hiberno-English ‘so’ of his father’s relations, a word that “operates as an expression which obliterates all previous discourse and narrative, and at the same time functions as an exclamation calling for immediate attention.” Perfect for the beginning of an epic poem.

Heaney there in the McClay alongside the ninth century encoders calling on our decoding skills couldn’t be more fitting, and both urging us to think again about how we learn and teach. Thank you!

Thanks so much for your comment Willard – indeed it’s a fascinating juxtaposition!