Black History month 2020. Black history online: colonies, resettlement, identity

The history of black lives in the United Kingdom and Ireland is built upon Britain’s colonial past, the history of slavery and the resettlement of communities. The administration of government generates vast sources and offers a useful insight into black lives in Britain via the papers generated: legislation, statistical and research reports and parliamentary debates.

In this blog post we will focus on the House of Commons Parliamentary Papers. This is a subscription database available to students and staff at Queen’s and can be accessed via the Library catalogue. Coverage ranges from the eighteenth century to the present day. Searches can be broad by keyword, or narrowed by date or type of document. A Key Terms list is also available to facilitate searching by theme.

As part of a wide view of citizenship and belonging, can we build a picture through these government papers and debates of black lives in Britain? What was the experience of black people who engaged with the British administration and settled in Britain over the centuries?

In 1786 Lord Sydney wrote to the Lord Commissioners to the Admiralty outlining a plan “for sending out of this country a number of black poor” to a new settlement in Sierra Leone. The “black poor” were “Black Loyalists”: slaves who had earned their freedom by fighting for the British during the American Revolution (1775–83). After the war and following their discharge from service, this group had settled in London, where they found poverty and “the greatest distress”. 1

The Sierra Leone project was flawed and hazardous. The settlement was vulnerable to disease and death and the Royal Navy was tasked with protecting both the colony and a neighbouring slave trade port. Although driven by philanthropists and abolitionists such as Granville Sharpe and William Wilberforce, the colony has since been regarded as a means to “be rid of the blacks as irksome beggars, petty criminals and … a threat to the purity of white womanhood”. Despite service in the British services and growing anti-slavery sentiment in Britain, there was arguably little room for black in Georgian British identity. 2

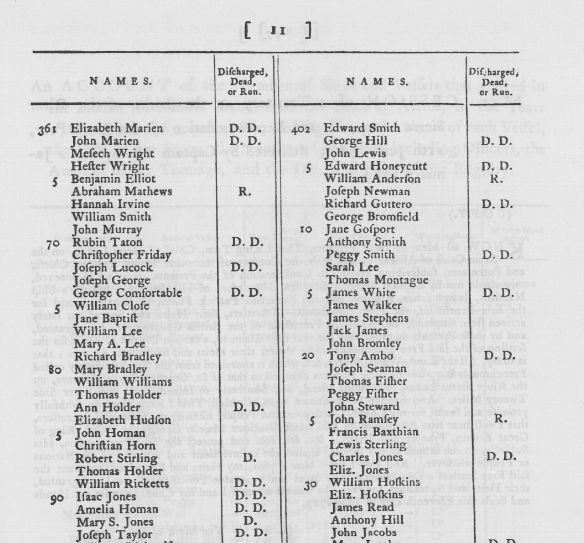

The planning and administration of the Sierra Leone settlement is detailed in parliamentary papers. This includes a list of the “black poor” who left London for the new colony in in 1787. It is also noted in the papers that, “of the 441 who embarked from England, only 268 remained by the time the Sloop Nauticus left Sierra Leone” and of these 122 died on the journey or shortly after arriving.

Papers Respecting The Free Negroes Sent To Africa. House of Commons Papers 67

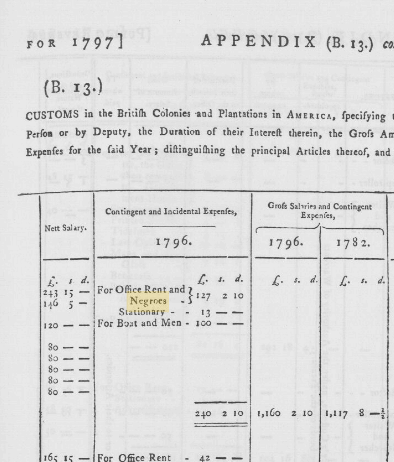

The detail of government accounts reveals much about how different communities of people are valued. We know that Africans served in the British Army and Navy from the eighteenth century. However, payment of African labour was separate from white labour: mainly listed with general labour “hire of negroes, labourers, horses, mules” , or listed separately alongside office rent, stationery, boats and, tellingly, men.3

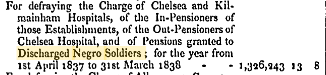

Although “free negroes” were an integral part of he British Army from the eighteenth century it isn’t until the nineteenth century that we see some reference to pensions.4 Pensions of “discharged negro soldiers” are noted in reports from 1821 to 1884 . This includes one Command Paper which called for “lists of these men” so that they could be put on the “books of the Chelsea Hospital” 5 We know from accounts published the next year that pensions for these discharged soldiers were included in the 1,300,000 allocated to the Chelsea and Kilmainham hospitals.6

Another chapter in Britain’s colonial history began with the passing of the 1948 British Nationality Act offering British citizenship to residents in British colonies.

The Act was motivated by the urgent need to rebuild post-war Britain. Events surrounding the consequent arrival of people from the Caribbean in the Empire Windrush to a Britain unprepared for immigration generated some debate in parliament and can be followed in HCPP. In 1948 a House of Commons sitting on 1st July 1948 noted that ”

Of the 223 West Indians who landed from the “Empire Windrush” and who were accommodated at Clapham, 148 have been placed in employment. Eleven are under submission and 49 await placing. There have been no difficulties in finding accommodation other than those normally encountered owing to the housing shortage.

Commons sitting of Thursday 1st July 1948

Further details were noted in September 1948 :

Of the 242 Jamaicans who were accommodated at Clapham, 23 left of their own accord and the remaining 219 were placed in employment.”

Written answers (Commons), Tuesday September 1948

Contemporary government debate around the issue of immigration to Britain and labour shortages offers useful background on immigration to Britain in the post-war years:

The other day we had the case of the “Empire Windrush.” It was not a very dignified affair. Those men paid their own fares to come to this country. Of course, all that could be done for them was done, but that sort of haphazard emigration is unsatisfactory, and, I think, dangerous. There is supposed to be a shortage of labour here. There is, I believe, a shortage of hospital nurses and ward maids. What about offering facilities for girls from Jamaica to come to this country to do such work? It would help us and they would get some first-class training. I hope that there are some such schemes in view.

David Gammans (1895-1957, Conservative MP) Commons sitting of Friday 4th February 1949 (Hansard)

Used with care, parliamentary papers can be a rich source for historians. Keeping keyword searches broad and reviewing results by dates enables a structured browsing approach – in this way we can find material online that we may not expect to find, the fortuitous discoveries usually confined to physical archives. The Key Terms facility in this database is also worth browsing, keeping in mind the terms assigned by government to colonial possessions.

- Papers Respecting The Free Negroes Sent To Africa. House of Commons Papers 67

- Land, Isaac. “Bread and Arsenic: Citizenship from the Bottom up in Georgian London.” Journal of Social History 39, no. 1 (2005): 89-110 ; Simon Shama, Death on the grain Coast,, The Guardian, Wed 31 Aug 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/aug/31/race.bookextracts.

- Thirty-Sixth Report from the Select Committee on Finance, House of Commons Papers. Parliament:2 November 1797 – 29 June 1798

- National Archives: Fighting for the Empire – https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/work_community/fighting.htm#:~:text=Black%20people%20were%20first%20incorporated,the%20Portuguese%2C%20Dutch%20and%20French

- Report of the commissioners appointed to inquire into the practicability and expediency of consolidating the different departments connected with the civil administration of the army. 1837. Command Paper 78

- Finance Accounts I.-VIII. of Great Britain, 1837. House of Commons Papers, 240