After the Siege

Andrew Hillier uncovers the story behind a family photograph taken in Scotland, one year after the lifting of the Siege of the Legations on 14 August 1900.

The scene has all the hallmarks of an Edwardian summer’s afternoon; a family gathering, with the women, serene if a little formal in their long white cotton dresses, the men looking like characters out of Elgar’s Enigma Variations and the neatly-dressed children (note the sailor suit), somewhat bored and itching to run free. But beneath the surface of this tranquil setting lies a very different story: just twelve months before, all three families had been in China during the Boxer Uprising, where they had undergone great hardships, with Bertie Tours and his baby daughter, Violet, both coming close to death.[1]

The photograph comes from a collection of albums and papers relating to Bertie Tours and his wife, Ada, arising out of his long-serving career in the China Consular Service.[2] Also in the collection is the diary which Ada kept during the Siege, meticulously recording the day to day events, save only for the time when the life of her daughter, Violet, hung by a thread. For this, it is necessary to go to Susanna Hoe’s account in Women at the Siege, which was based on what she was told by Violet’s daughter, Susan Ballance:

At some stage, my mother [Violet] was taken ill, and she was put outside her room as she had been pronounced dead. The wife of the French Ambassador [Mme Pichon] passed down the corridor, found her, picked her up and insisted there was life in her after all. We were always told that it was she who found an egg to give Violet, which put her on the road to recovery, and decided the Saving of the Baby was to be the Ladies’ Project for the Siege. Because of all this, Violet became known as ‘The Siege Baby’.[3]

Apocryphal it may be, but the story certainly became part of the Tours family mythology. Although Violet survived the Siege, she continued to be very weak for many months, whilst her father, Bertie, contracted meningitis and nearly died.[4] In need of an extensive period of convalescence, he and the family left China in November 1900 and arrived at Southampton on 20 December. They were accompanied, so the passenger list says, by ‘a servant’, Mrs Lu Ching, who must have been Violet’s amah, but sadly, she is not mentioned again and there are no photographs of her.

The following summer the Tours family travelled to Scotland to visit the Brazier brothers, both of whom were serving in the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs (IMC), presided over by Sir Robert Hart (the Inspector-General, ‘IG’), who, despite losing almost all his possessions, was continuing to adopt a conciliatory approach towards the Chinese. Given the photograph caption, the Tours were presumably staying at the Brazier family home in Aboyne, Aberdeenshire. As Chief Secretary of the IMC, Russell and his wife, Helen, had also been holed up in the legations during the Siege and will have come to know Bertie and Ada well during that time, if not before. Helen was the daughter of the long-serving physician to the IMC, Dr Wykeham Myers (1846-1920), who had made his name in Tamsui, Formosa but had been attached to the military base in Tientsin (Tianjin) during the siege of that city. He had arrived in Peking with the British forces on 14 August, not knowing what to expect, and whether his family had survived. He then had the intense relief of being greeted by his son and daughter-in-law, and their two children.[5]

Born and brought up in China, Helen had married Russell Brazier in 1893, when she was just nineteen and he was thirty-three. Willie was born the following year and, although she lost her second baby at birth in early 1899, she was soon pregnant again. Helen Hope was born on 17 December and her mother was probably still nursing the child when the Siege began on 20 June the following year. Helen’s sister, Annie Myers, was also in the legation and went to stay with Bertie and Ada Tours.[6] Russell’s brother, Harry, was in Shanghai and, although safe, will have anxiously watched the events unfold, particularly when rumours spread that everyone in the legations had been killed.

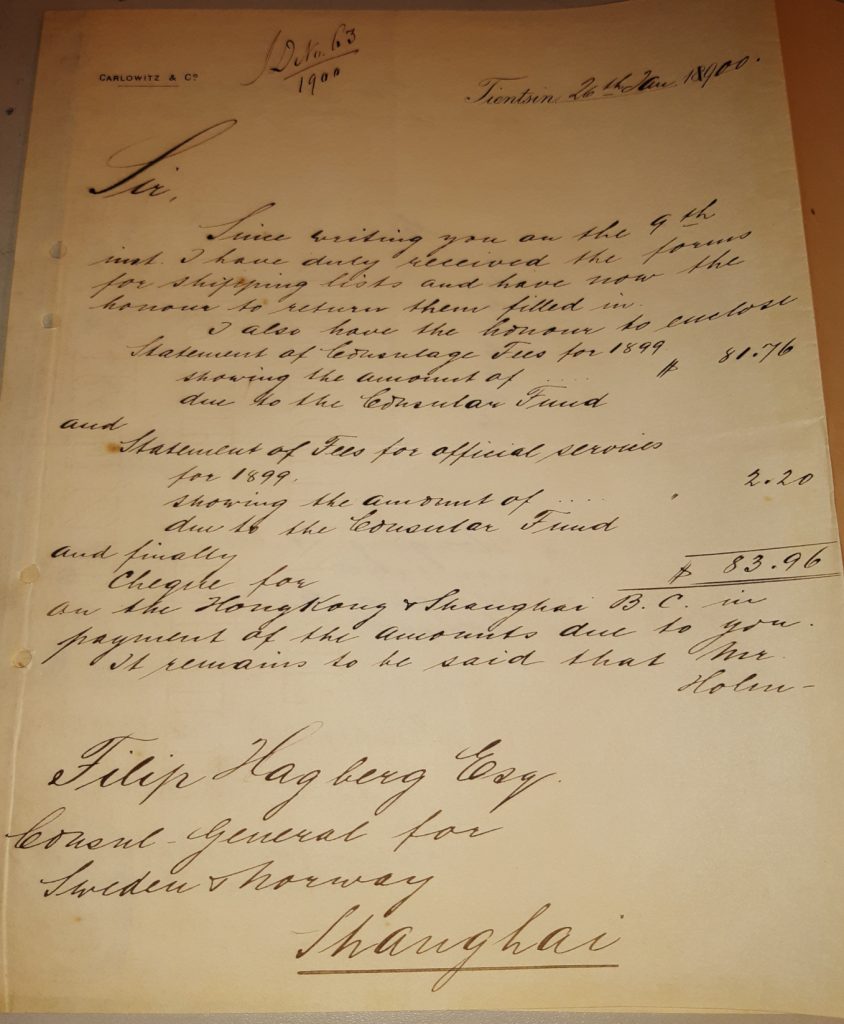

But, who was the fourth man in the photograph, Carl Albert Holmström, and what was he doing in Scotland with his wife, Katherine, and two children? The answer is that they had also been caught up in the Boxer Uprising. A census record prepared by the Swedish/Norwegian General-Consulate at the request of the Statistical Department of the IMC for 1900 describes Holmström as an engineer and shows that the family were living in Peking and Shanghai. This is confirmed by a letter from the Consul-General for Sweden and Norway, Filip Hagberg, dated 26 January 1900 setting out the consular fees that Holmström paid for 1899 – see figure 2.[7] Interestingly this document is written in English, possibly because he had taken up residence in England in 1890. It was there that he had met and married Katherine, who, although also Swedish, had been born in Manchester. At one point, he was employed by the arms manufacturer, Maxim Nordenfeldt, and it may be that this was why he was in China; if so, it may have been on their behalf that he had had dealings with the IMC. It is clear from entries in the North China Herald that he and Katherine had arrived in 1896 and that, by 1900, they had both become well-known in Peking, attending important social occasions and with Carl playing a lot of golf. Evidently, it was through these connections that he and his wife knew the Braziers.

However, they do not seem to have been in Peking during the Siege. An entry in the NCH for 18 July 1900 states that both Carl and Katherine were in Tianjin when the railway was cut and that they had ‘the misfortune’ of not being able to get back to Peking. This was probably where they remained with the two children. If so, they will have shared in the terrifying experience of the western community in Tianjin, when the city was also besieged. On 16 August they left Shanghai for England and, it seems, did not return. In 1905 Holmström became a naturalised British subject.

After the trauma of the previous year, the three families must have enjoyed their time in Scotland. At least partially recovered, although still unforgiving for what had they had been put through, Bertie returned to China at the end of the year accompanied by Ada and Violet. However, Helen would not return. At the time the photograph was taken, she was already pregnant with her fourth child and, on 4 January 1902, Beatrix Alice Russell Brazier was safely delivered. But, soon afterwards Helen fell ill, having developed blood poisoning, no doubt weakened by her experiences in the Siege. She died on 12 January 1902.

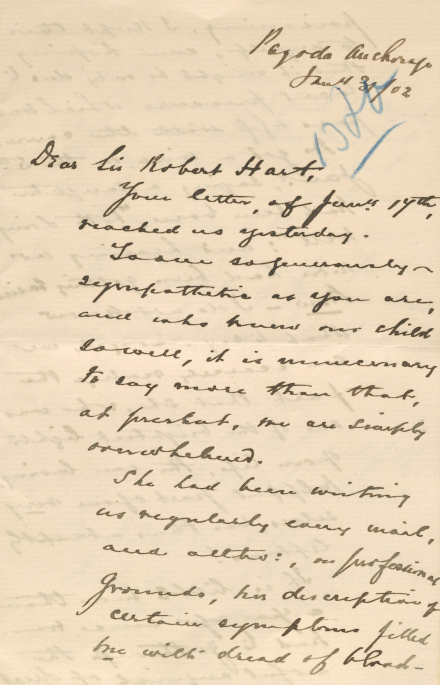

Three letters from her family to Hart in Peking, tell the sad story and show not only how global the British World had become but also how intimate contact could be maintained across that world. [9] Hart knew both sides of the family well and had agreed to be the child’s godfather. Writing from Pagoda Anchorage, Fuzhou, Helen’s father, Dr Myers, thanked him for his letter of condolence, saying, ‘To one so generously sympathetic as you and who knew our child so well, it is unnecessary to say more than that, at present, we are simply overwhelmed’. As would so often happen in such cases, some weeks after hearing by wire of Helen’s death, he received a letter which she had written just before the baby was born – ‘verily a voice from the grave’, as he told Hart.

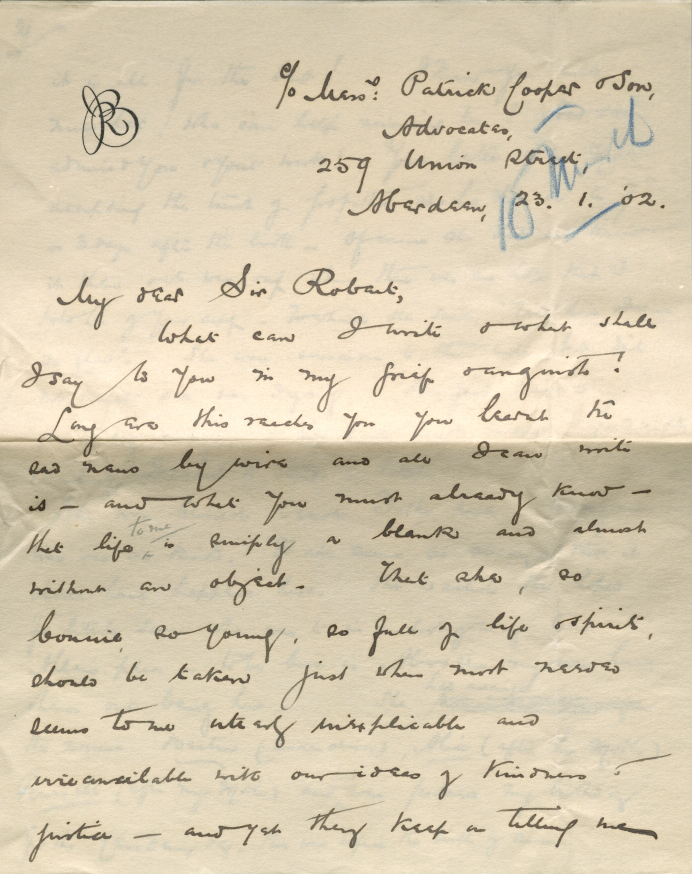

Helen’s widowed husband, Russell, also found Hart a sympathetic listener, confiding in him,

That she so bonnie, so young, so full of life and spirit should be taken just when most needed seems to me utterly inexplicable and irreconciliable to our ideas of kindness and justice…

Helen was buried beside the Brazier brothers’ father in Aberdeen. Harry Brazier was about to set off for China, as he told Hart in his letter, travelling across France and catching a boat in Genoa. Russell returned later that year, having made arrangements for the care of the three children. Aged seven, three and less than a year, this will have been a very lonely start to their lives. But they all survived into adulthood and how they made out is a further story, waiting to be told. Willie died in 1955, Beatrix in 1982 and Helen Hope, who was barely six months old when the Siege began, died on 17 December 1999, her hundredth birthday.[10] Just five months earlier, Susanna Hoe had met Helen and it was to her, ‘the last survivor of the Western women in Peking’ that she dedicated her account of that extraordinary episode.

Dr Andrew Hillier

Honorary Research Associate

University of Bristol

My Dearest Martha: The Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier (ed. Andrew Hillier) was published in August by City University Press of Hong Kong. Andrew is now researching for a study of consular wives and would like to hear from anyone with unpublished family papers or photographs relating to China consular families.

ah12387@bristol.ac.uk

andrewhillier.org

[1] For the Uprising, generally, see Joseph W. Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1987).

[2] The Collection is housed at Abercamlais, the home of Anthony and Andrea Ballance and I am extremely grateful to them for allowing me to spend a fascinating day viewing the albums and papers. Anthony is the great grandson of Ada, descending from Violet, whose husband, Captain Nevill Garnons Williams (as he became), inherited the estate from his father in 1935 and whose daughter, Susan, married Anthony’s father; cf. https://www.abercamlais.com/family-history/

[3] Susanna Hoe, Women at the Siege: Peking, 1900 (Holo Books, Women’s History Press, 2000),pp. 244-245. I am grateful to Susannah Hoe for allowing me to quote from her book and providing me with further useful information.

[4] Hoe, Women at the Siege, p. 306.

[5] https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/william-wykeham-myers-early-medical-education-in-china/ Hoe, Women at the Siege, pp. 235 and 369, n. 19.

[6] Hoe, Women at the Siege, p. 61.

[7] NationalistMatrikel https://sok.riksarkivet.se/bildvisning/90000001_00105#?c=&m=&s=&cv=104&xywh=-2176%2C-214%2C9104%2C4261

I am extremely grateful to Liv Christensen livbchr@online.no and Kjell Halvorsen for doing extensive research to obtain this information for me.

[8] Ladda hem fil: https://pub.riksarkivet.se/handlaggarstod/48f480d0-bdc4-4a20-8686-0e7b72ffb194/Holmstr%C3%B6m%20utebliven%20avgift%2C%201.jpg Copies of documents can be ordered from the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs up to 1920 https://sok.riksarkivet.se/nad?Sokord=Utrikesdepartementet

[9] Many thanks to Deirdre Wildy and the team at Special Collections, QUB, for much assistance and providing me with copies of these letters.

[10] See Hoe, Women at the Siege, p.372n 58.

Further links:

- Digital Exhibitions: Sir Robert Hart 1835-1911 Exhibition. We also have a Chinese language version

- Browse our blog posts for more information on Sir Robert Hart and the Hart Collection

Who would have thought such extraordinarily dramatic events had preceded this seemly, on the face of it, unremarkable family photograph? A thoroughly enjoyable read.

Wonderful blog Andrew! Claire

A very interesting read, thank you. I am one of the grandchildren of Helen Hope Brazier/Steedman.